Welcome to Water for Teachers, A Heinemann podcast focused on engaging with the hearts and humanity of those who teach. One thing we know for sure is that teachers are human. They have fears. They've experienced tragedy. They struggle. They are affected by crises and pandemics. And like everyone else, they deserve to lead lives full of peace, joy, and love. Join host Shamari Reid and other educators as they move from logic to emotion, from the head to the heart, from thinking to feeling, and from the ego to love.

For this series finale bonus episode, Shamari is joined by Cornelius Minor, a Brooklyn-based educator and Heinemann author, as they discuss the impact the pandemic has had on teachers, the endurance of American racism and anti-Blackness, and imagining a better future.

Below is a transcript of this episode.

Shamari: I am beyond excited because today I have the pleasure of engaging with the heart and the humanity of a brilliant human who teaches, Cornelius Minor.

Cornelius is a Brooklyn-based educator and a part-time Pokémon trainer. He's also the author of We Got This, an incredible book that explores creating more equitable school spaces. These days, Cornelius is learning how to bake from his two young children, searching for an elusive pair of Jordan 4s and ritually rereading all, and I mean all, of the 1990s era comic books that he can find.

But before I speak with Cornelius, I want to start off today's episode with a letter. After, I'll invite Cornelius to explore any and everything the letter brings up for us both. The letter I'm going to read as one I wrote for you, for all of us.

Dear Fellow Teachers,

As I write this I will not pretend that things for us are normal. They are not, and I have come to accept that things not being normal is okay. We are living through a pandemic, a time of collective crisis. I also recognize that due to our different identities, undeserved marginalization, and unearned privileges, we are not feeling the effects of this crisis equally. Perhaps like many of you, since the arrival of COVID-19 into our lives I have experienced extreme feelings of helplessness, coupled with fear and anxiety. And I have found myself lost within extended moments, absent the motivation to complete things that used to excite me like engaging with my students work, reading Toni Morrison, writing short stories, or planning lessons, or cooking.

Where has my inspiration gone? There was even a time in which I spent no fewer than 24 hours in my bed, clenching to my comforter with the lights off and the shades drawn. As I kept my bed company, ensconced there in the darkness, my mind wandered. I reminisced on the way that things were before COVID-19. I recalled greeting my students as they entered our space and marveling at them while they collaborated with their peers on class activities. And if I was not longing to return to the past, I was dreaming of what life would be like after these trying times. I told myself that awaiting us, all of us, on the other side of this epidemic was the world we deserved.

However, once I realized that I had no control over time, thus no way to be certain when and if we would ever get to know that world, the fear and anxiety intensified, the feelings of powerlessness and helplessness returned, and 20 minutes became 28 hours. To cope, I decided to have a vulnerable and honest talk with myself. I'll end this letter with the words that I told myself during that conversation about our current state, words and questions that brought me some peace, and I hope they do the same for you. You are living in a pandemic, your sanity and wholeness require that you accept this truth. Resisting this truth will not serve you or your students well.

This is the only reality you have, the only one that matters. The past is no more, and the future is not here yet. So how can you move through this present moment with happiness, peace, and love? What are you able to do right now to make your current reality more enjoyable, teaching more enjoyable? What actions might you need to take to move beyond simply trying to survive this until something better comes along, to thriving and living your best life right now?

I love us for real,

Shamari

Now I want to invite Cornelius to engage in a conversation with us. Welcome, Cornelius. Welcome. Thank you for sharing this space with me.

Cornelius: Well, Shamari thank you for that letter. I needed that. I feel like the podcast can be over now. I mean that's really ... I wonder what you need me for. Oh wow. Thank you, and I'm really just living in that with all of my identities. And it's so interesting that this is a podcast for teachers because I have been living most profoundly and most loudly as a father in these times. You know, that when our classrooms evaporated in March and my ability to leave my apartment was limited, the thing that was most pronounced in front of me was my family, and guiding my two daughters through this alongside my partner. So what's been interesting is, as I reflect on your letter, I remember the moment when I was telling myself all of those things, but about fatherhood.

That I couldn't hide. I couldn't run. I couldn't live in the past. I couldn't hope for some kind of like rainbow future, but rather I have to live in the very real now that my children were experiencing. So I'm just like, all of my daddy sensibilities are firing right now as I think about that letter. And one of the big things for me that I have been channeling is, I went not to the past, the nostalgic past, but to the historic and to the ancestral past. And I have really been asking myself almost every day is, "How did our people love their children through the kidnapping from the West African Coast? How did our people love their children through the Middle Passage? How did our people love their children through chattel slavery and through forced separation of families?"

I've been trying to tap into that strength really, and to love not just my biological children, but to the 32 children assigned to me by the City of New York, and the teachers under my care as a coach. I've really been every morning when I get up like, "How do I find the strength to love the children in front of me through this pandemic?" But a lot of it is channeling the strength of our forefathers. So I think a lot about like how Harriet loved. I think a lot about how even fictitious characters in books like Beloved loved, and I'm really trying to be that love. Like not just trying to enact that love, but trying to be that love.

Shamari: Let me ask you this, and it might be an abstract question in a weird while we're in COVID, but I feel called to ask you, how is your heart today?

Cornelius: You know, it's in a lot of different places. One of the things that I know that I do, and I'm working on this, that I know that when the world gets heavy, I know that I callous myself against the world so that I can do my work, so that I can serve my family, so that I can protect my community. And I just know that that's Cornelius's trauma response, right, when things get heavy. So I do what toxic masculinity has taught us to do. I put on my tough-guy face and I fight through. I know I'm in that right now, and I know when I'm in that I need to address some things, and I need to work through some things. What's interesting is, this pandemic has actually been a bit of a paradise for me, that I travel a lot. I spend about 12 to 14 days a month on the road.

So that's half a month I spend away from my children serving teachers and students around the world. So this March when physical classrooms shut down, this March, March 2020, was the first time in the lives of both of my children that I have been home for more than two weeks. So really when the pandemic hit the hardest, and especially here in New York, there were days when we were losing one, two, three hundred people a day. You know? So even when I reflect on the experience of New York, everybody lost somebody. Right? But when those days felt darkest outside of my apartment, they were most light inside my apartment just because I enjoyed the company of my children. That they have gotten used to asking the question every morning when they wake up, "Is daddy here?"

You know, when I'm usually in some far away hotel. You know, doing important work, but still work that kept me away from my family. So this March when we were really on the one hand outside my apartment for my community we were suffering, but inside my apartment, I was really just getting to know my kids. I know them, but now I feel like I know them know them. So from March to like July, we didn't go anywhere, and it was every morning we're playing games, and I'm reading you stories. Like I read my daughters The Lightning Thief from front to back, all the way through it, and I read them all of Kwame Alexander's books. We read Renee Watson together. You know?

And just that they'd never experienced ... Like every kid in America it feels like has experienced or read aloud from Mr. Minor except for my own two, and so I just like relished in that. So for a long time my heart was great. But then the summer is what it is in America. You know? And when we say it's hot outside, when brown folks say that, we mean that these people out to get us in some kind of way through the erasure of rights or the denial of access to resources. And this summer particularly it was the reminder that the police will come get you and no laws will hold them accountable. So this extra-judicial killing of Black folks with Breonna Taylor and George Floyd I found myself kind of slipping out of that like nesting mode back into combat mode. I know how to fight these fights really well.

One of the things, I talk to my dad about this all the time, and my dad hates that it is this way for me, but he was like, "Cornelius, you're a born fighter," that "You thrive in this kind of intellectual and spiritual combat, and you're good at winning those battles for people." But he's like, "I wouldn't wish that on anybody, and I'm really sad that my son has these gifts." Often I look at myself and I'm like, "Why is my talent the one to go out there and fight? Why couldn't I play a trumpet? Or why is it my talent to go and fight these sometimes unwinnable fights?" So I felt myself slipping back into that mode where specifically with Breonna Taylor that got me. Like, again, I have daughters. Right? You know? And I put them to bed every night.

I was really proud of that because I wasn't in hotels, I wasn't flying, and so I know what it is to watch Black girls sleep. You know? So that was real for me. But yeah. So I'm back in the combat because after that it was, how do we start school again, and protect our children, and protect our teachers, and protect our families. Then it went from there to this election and really ... Knowing what I know about America, I knew what it was. Like I knew what it was before Trump. You know, that people like to think that these problems are 45 problems. These aren't 45 problems. These are problems from the Articles of Confederation. These are problems from the Constitution. Like we ain't been humans since they took out pens.

Shamari: Wait. So knowing that and that truth, and saying that this is not new, that there's just a history and a legacy, if you will, and then you add on epidemics, right, what compels you to fight? Why not give up? Why not be like, "Yo. I'll chill with my girls. I'm going to have whatever, some kind of beverage. I'm going to chill. I'm not going to fight." Why go out there?

Cornelius: Because I know how beautiful we are. You know, I see us. I've seen magic before, like in a real way. Like people joke all the time, or we say in jest to each other that Black folks are magical. But I've seen it. I taught in the Bronx, and I know what it's like to watch the kids walk to school. I've been out here in Brooklyn. I know what it is to watch the kids wield words like swords or wield words like comforting pillows. Like I know what that is. Right?

Walt Disney says that, magic is when reality exceeds expectation. Right? That idea that the reality that we're living in only has certain things set aside for us, but then every day our children go out and make better. And they do it effortlessly and with style. And so when I think about why the fight, because so many people fought it for me. I can name all the people who stood in the gap for me. And I get to live this life in this beautiful city because of my babysitters and my Sunday school teachers and the bus driver, and the lady who worked at the bodega who used to give me food for free when I couldn't pay for it.

So all of those people fought in those small ways so that maybe one day I would have a shot at fighting in these big ways. And so, I fight to honor them really. There's this marriage of past and future. There are young people that I serve, but there's all the people who made small sacrifices. And so I think that's it.

Shamari: Yeah. You bring that up and you're taking me back to something you said earlier, just about holding space to reflect on all the people who have come before us, who have given up things, who have made sacrifices so that you and I can be having these conversations. And for me, that always goes back to love. And so when folks ask me, "Why are you here?" It's because someone loved me enough to sacrifice, to extend themselves. You know what I'm saying?

Cornelius: Yes.

Shamari: You don't even know me yet, but I am here. And so when I'm hearing you now say is you're doing the same thing because how beautiful we are, because you love us for real. That you're willing to fight. You're willing to maybe not always be there to tuck in the girls, those are sacrifices Cornelius.

Cornelius: Yeah.

Shamari: Make the sacrifices that I'm sure you're seeing now because you'll get home and you're like, "I've missed some of this." Only love I think... People have their different thoughts about love, but only love can move us to make those kinds of sacrifices to improve the lives of people we don't even know yet. Of course those we know, but for the generations of young people to come.

Cornelius: Absolutely. Absolutely. And everybody who's here now been here before. And so even for the kids in St. Louis that I don't know, or for the kids in Los Angeles that I don't know, for the kids in South Florida that I don't know, they've been here before. So we know each other some kind of way. When I meet kids for the first time, especially because I meet so many kids around this country, one of the things I love telling them is I love talking to them about who I sense in them.

So I love meeting little boys and being like, "You sound just like Frederick Douglass to me. And let me tell you who that is." Or I love meeting young kids and being like, "Yo, you sound just like Mary McLeod, but though let me tell you who that is." And I like to tell these kids, "We've been here before. So this energy you've given me right now, that's that Louis Armstrong energy. You're going to take something real crappy and turn it beautiful. And I see you right now." And so I love meeting kids and helping them to understand that all of this has been prepared for us, and we're going to move forward in really powerful ways.

Shamari: You're making me think of something you tweeted... Oh gosh, I don't know, last week. Maybe the other day. But it was from... And let me say this to all the comic book readers out there. Hi comic book readers. I don't know how many.... I need Cornelius to help me out. But there was a photo from, I think New Avengers, number one.

Cornelius: Yes. New Avengers number one yeah.

Shamari: I'm looking at it here and again, I'm not comic, not that I'll I read it, please fill in the gap, but it looks like Black Panther, okay.

Cornelius: Yes, it's Black Panther.

Shamari: And there are some other characters with him, but when he says this and I'm going to just read from the photo you tweeted, " Pride. Pride and not shame, which is what we feel for the world out there. Great societies are crumbling around us, and the old men who run them are out of ideas. So all eyes turned to you, our children to build us something better." And you tweeted saying this was your why. Say more about one, what happens in New Avengers for those of us are not into that. But also what do you mean this is your why?

Cornelius: I've been a comic book fan since jump. Since I could be like... Actually the first book I read from cover to cover was Hardware Number One by Dwayne McDuffie. So my literacy life is built around comic books. Specifically...

Shamari: Your book is a comic, right?

Cornelius: Yeah, and my book, that's the style that I write in that is the intelligence that I bring to any task? And so people like put you do research but that's how I see it. So even when I'm looking at statistics and data, I see it in graphic, novel form in my mind. And so when I produce scholarship, that's how it comes out of me, just because I consume so much of it as a young person and even still as an adult. And actually the way I learned how to make change in the world, the first letter I ever wrote was to Dwayne McDuffie. After I've read that book. I was a non-reader for a long time.

I read that book from cover to cover. I was so moved. I wrote him a letter to tell him how moved I was. And he was so moved by my letter that he published it. And so the first thing that I ever had published was in Hardware Number seven. And so twelve-year-old Cornelius minor wrote a letter to the author of this comic book and he thought enough of that letter to publish it in the book.

And I was like, if I write to people, I can be published. And so my whole career really started in those moments, but New Avengers number one, it's the beginning of the end of the world. And Black Panther, he is in Wakanda and the beginning of the end of the world starts in Africa where it began. And he is watching this happen, and essentially he's like not on my watch. As long as I have children, children who can live on my legacy, ain't going to happen here. And I just love that declaration that, that you might see me, but you ain't going to see my children.

And I feel that way as a father, I feel that way as an educator that we can pour everything into the people who are coming after us. And what's interesting is the world is literally ending and all of these superheroes have to come together to do it and nobody's superpowers are effective. And it turns out that the thing that ends up saving the entire universe is his belief in his children. Yeah.

Shamari: I am now a comic book fan. I've been missing out my whole life.

Cornelius: Yo, but comics are for real, it's not just comics. A lot of people don't realize this, but I studied Afrofuturism. That was one of my areas of study in graduate school. So I have a literature degree, which when you go to graduate school, you figure out where you want to take it. And I was profoundly interested in the presence of African people in the imagined future. And at the time there were so many mediums that would construct this utopic or idealic future, but they would construct it without Black folks. And so the question that I always ask is like, what does that say about your present? When you imagine a perfect future, and you imagine that perfect future with no Black folks in it, what does that say about your present?

So something as simple as like The Jetsons, for example. When you watch The Jetsons, they know bro in The Jetsons. So you're selling this idea of a perfect future where robots assist us with everything, but somehow you remove all the Black folks or there were one or two characters. And I really connected a lot with my past. I'm Liberian, I'm from Liberia, right? And the central trope in a lot of contemporary science fiction is that some wrong with earth, we got to go to a new place. Right. And so this idea, that space is the place and that was embodied in the music of Sun Ra, or in the music of George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic. The idea that we're going to catch the mothership because hearing the place. But that connects back to the Negro spirituals, Swing Low Sweet Chariot, Comin' for to Carry Me Home, so that we got to get out of here.

And that whole Sci-Fi it feels the more I started studying it, the more I realized that's really who I am. When you study the story of Liberia, for those of you who are listening again, Liberia was founded by formerly enslaved people who left this country and returned to the African continent. So the idea that here ain't okay, I'm going to find another place for me. When I was reading all this Sci-Fi, I didn't realize that it was already in my DNA. That my people, three generations before this, left this continent and went back to Africa. And so I was really just interested in all of the different ways that Black folks have imagined themselves in the future. And have projected that imagination onto our current reality and onto our children and also our literature and onto our art and onto our dance.

That's the kind of stuff that energizes me. So, when you watch Black kids dancing, that's from the future. They're dancing through this now, but what they are articulating with their bodies is that there's a better place for us. And we going to make that place right here. When you watch Black kids in the cafeteria joking on each other and joking on the systems that keep us stuck where we are, that joking is like that's the liberatory force. Right. But I'm sitting where I'm sitting, but these jokes can take me anywhere I want to go, these jokes can take me to the next cafeteria table. And so I just love that idea that, that everything that we touch, everything that we see when we filter it through our imaginations, we are living science fiction, and all that we've been able to accomplish is just like science fact. They're like that we have been able to do things that people can't explain.

And I just absolutely adore that, that people are like, Well, how is it that people persist? How is it that people raise children? How is it that people create this beautiful art? And I'm just like, you don't ask how to magic. What Langston did was nouns and verbs and adverbs, but what Langston did was like ethereal and ancestral, right. When we think about the music that was the jazz, what Miles did. When we think about the music that is the hip hop, we think about what Kool Herc did, all of those things. People always look and ask how, and I'm like, nah, "Like how," is the wrong question. The question is like, "Why did you create the conditions that force people into these postures?" To have to create these things?

That America loves to excuse itself by saying, "Oh, we put Black folks these adverse conditions, and we got jazz. So aren't we great?" I'm like, "Nah, we should never have them conditions in the first place." So this by-product is just turning poison into honey. So that's the stuff again that excites me, this is my why. And so when I read Black Panther, when I listen to hip hop, it just reminds me of two things. A, how messed up this reality is for so many folks, but then B, our ability to craft this reality into something better.

Shamari: Are you afraid of anything?

Cornelius: I have an interesting relationship with fear. And again, I tend to callous myself against the world. The other night... I am afraid of things, but I do not... My relationship to fear isn't a traditional relationship to fear anymore, but I am very afraid of things. And I process this a lot through writing. I'm afraid that my daughter is living in a world that is never going to respect their humanity. All the time, I could think about that every second. But my relationship to that fear is not one defined by paralysis. My relationship to that fear is almost manic. I can't stop working. And I know I won't achieve us all, or I know I won't discover the thing, but, I want them to see that their daddy fought every second.

Yeah. So that's, oh yeah. But fear in a big way. This was when I was 19 years old, my friends and I were victims of a hit crime. Somebody planted a bomb in a classroom, in a building where I was studying. This, I was in college. I went to Florida A and M University in Tallahassee, Florida. Historically, Black college. Founded in 1887 and this white supremacist came to campus and planted a bomb on the campus. And this was before September 11th, 2001. So, our country did not have a discourse or language for terrorism. There was no language to describe what had happened. Right? And I remember being on campus during that time. And at the time I was student body president, and I remember talking to my father about what you do in a situation like this.

I mean, I'm 19. I grew up in the eighties, so I understood gang life and drive-bys and things like that. But people putting bombs in your classrooms? That was some GI Joe type stuff. That was just like, I had no context for that, but my father did. Right? My father survived the civil war in Liberia and I, as a young person, I don't remember it, but I lived through part of that. And my father reminded me of that. He says, "Son, you have lived through part of a civil war. You don't have active memory of it, but it is in your experience that you have lived through things like this before."

And I remember him urging me to stay on campus. And he was just like, "You got work to do. That your friends have not lived through a thing like this before, but, but your people have been bombed before and you were an infant, but you have been through it." And so he's like, "There are things inside you right now. And there are things that you can do right now that other people can't. And so, I need you to stay on that campus and to help people make sense of this thing that is very much senseless." And he's like, "It is not your responsibility to do so, but somehow I sense it's your calling." And those are words that I continue to grapple with. Right? Like the things that you want to do versus the things that you were called to do.

Shamari: Did it ever feel too heavy, Cornelius?

Cornelius: Absolutely. But I'm also blessed to have really powerful friends. I say all the time loudly and as often as possible that my partner is the best person on the planet earth. Shout out to Cast Miner, but she sometimes will talk about a thing and I'll be like, "I'm not even going to say this to her because she's going to think it's impossible," and I'll just say it to her. And she'll be like, "Oh, well maybe we can do that by Tuesday." And so, I'm around people who don't think in terms of impossibility or limitation. And so, I'm really lucky in that regard that both my blood family and the family that I've curated around me here in Brooklyn, people keep me loved up. And I am so grateful to all of them.

When I think about how I even got to college, one of my Sunday school teachers was this woman named Ms. Jones. And she was a retired teacher and living on a fixed income. And I remember when I got accepted into college, she gave me a card with $5 in it. And then she told me, she's like, 'I don't have a lot of money to give you, but this is what I got. And then I want you to take this $5 and you can do something." And I remember knowing how much, $5, what it was to her. And my mom made sure I didn't forget. My mom was like, "That $5 was what she had set aside for part of this week. So she's going to miss a meal or two this week for your college fund." And so, all of this stuff is heavy, but when it's heaviest, I remember I'm like, "Yoh, people have made real and present sacrifices for me to be able to carry these things." And so-

Shamari: You are loved and you know that. Because you know that, you get to owe and gosh, I don't know, create the world that you deserve. Right?

Cornelius: Yeah. And so, when we think about, going back to your original question of what keeps us going, I hope that the kids that I interact with feel as loved as I felt coming out. That again, the people in my church, the people in my neighborhood, the people in my school, everywhere I went, I knew that my Blackness was beautiful, my brilliance was beautiful, my mistakes were beautiful, and not in any artificial kind of way. Where people still let me fail and people still let me be a knucklehead. And people still punish me when I need a punishment. But it was never in this sense of, "Cornelius, you were lacking. It was, "Cornelius, the whole universe is inside of you. Why did you let us down?" Or, "Cornelius, the whole universe is inside of you. Why aren't you living up to your potential?"

And so, at every corner, even when people were dissatisfied with me or angry with me, I knew that I was loved. And really that's my pedagogy, that even when I'm angry with kids, even when they have not met my expectations, I want them to know that yes, even your mistakes are beautiful. I'm still holding you accountable, but your mistakes are absolutely beautiful. Yes. Even your shortcomings are beautiful. I want people to just be so much of the discourse of who we are, not just as Black folks, but as humans, as teachers is about the things that we lack. And so, I always want to lean into that notion of abundance that I want the discourse to be about the things that we have.

Shamari: I was trying to look for the author. When you were talking, you said something that sounded almost like this quote that I'd heard, and I randomly stumbled upon it one day Googling. I forget what I was Googling, but I was getting ready to talk to my mentor Yolanda Sally Rowley. We're going to talk about, and I was on Google and I clicked the wrong place, but I got to this quote and the quote was, you can't teach kids, you can only love them. And I don't remember the author of that quote right now, but I'll definitely make sure I include the information, in the episode description. But that idea that you can't teach them, you can only love them, make sure they're loved up.

Cornelius: Yeah, absolutely. And that was my whole upbringing. My whole upbringing. Everywhere I went, from the candy store, to the boutique. Everywhere. And even instances that didn't feel like love as I reflect on them now. And wanting to make sure that I do so in ways that are not selfish, right? That I think about John Coltrane and when he tried to attempt to define love in a love Supreme. When I think about Bell Hooks, when she writes all about love.

And so, I'm always wanting to make sure that the thing that I love in other people or the things that I love in other people are not things that are tied to my aspirations or desires, but rather are things that exist in them purely because they are in them and they are beautiful. And so, so much of what we call love sometimes when we say we love our students is really a love that is tied to the transaction of their ability to do assignments for us or to the transaction of them doing what we say when we ask them to do it. And so, I'm really trying to move away from that and to say "When I love you, I love you absent of my aspirational connection to you or absent of my expectations of you."

Shamari: And it doesn't depend on the things that you will or won't do. It's I love you right now in your current state, in this present moment, whether or not... Whether you perform the way I want you to or not, I love you. And I think that goes back to what I was trying to tell myself earlier in the letter is, stay present. Stay present. This reality is all that you have. This young person in front of you, they are who they are. It's all about them. Not how do you feel next week if they do these things.

Not, "Oh, what will you do when they..." I don't know, do something that you might think is an act of defiance. But in this present moment, do you love them? And I think that it's so, so important that for me, the answer is yes? The answer has to be yes. It must be yes. And if not, we need to sit with ourselves man, and do real internal work. If you feel that you aren't able to love your students in their current state, regardless of the things they do or don't do for you. If you're waffling or wavering between, do I? Do I not? It's time to take a seat.

Cornelius: Absolutely. And I take that seat often. I spend a lot of time teaching myself or learning from students how to love them. I think that part too, that these conversations about teaching happens sometimes where we talk about what it means to kind of step into our full humanity as teachers, but we also don't acknowledge publicly. And so I want to make sure they acknowledge publicly that there are times, lots of times, most of the time, where I cannot, for some reason, or I have not, or have failed, to step into my full humanity as a teacher.

And so, part of being truthful is acknowledging the times where this is a time where I fail to love this student, or this is a time where I've failed to love this group of students. And so taking that seat that you are just to take and really reflecting on that and being like, "Well, why didn't I?" Or, "Why did I fall short?"

Even this week, we're coming up on Friday and on Monday, I let, it's assessment season. Right? So we've got parent-teacher conferences coming up and I started stressing out about parent-teacher conference just because it's been so difficult to even think about grades right now. Right? What is a grade in a pandemic? And so, I started panicking. What am I going to tell parents? I don't have papers to show them like I used to. Right? I don't have notebooks that I can say, "This is what your kid did on Tuesday." So, all of those things that I used to have, those artifacts that would communicate kids proficiency in any number of areas, I don't have those right now.

And so, in my panic to assemble something that I could grade on Monday, instead of preparing my kids emotionally and intellectually for the week that was ahead of us, I started panicking and demanding that notebooks be turned in and papers be submitted. And I lost my mind for 50 minutes, just a period, but for 50 minutes, I started believing the hype that I needed some kind of grades. And I lost my mind for 50 minutes. And I remember as people were leaving the Zoom room, this one young man was just like, "Yoh, I thought you was going to talk to us about the election coming up. You always prepare us for things, and you didn't today. So we've got to go into Tuesday and we don't have a word from you right now."

And I had forgotten. I just... Because notebooks. Right? Because grades. Because parent-teacher conferences are coming. And again, it was one period. So I was back in my position of love for the next period, but I needed to take that seat. I needed to really sit with myself. And unfortunately, we have three minutes before the next group came in to sit with myself. But I was like, "What are you doing Cornelius?" That like, "You were stressing kids about notebooks when a lot of kids are stressed about their immigration status. When a lot of kids are stressed about their parents' employment status, specifically given the outcome of this election. Right? So, having to put those things in perspective, that your stress over a notebook, when some kid is thinking that the reelection of 45 might mean the third immigration status is imperil for real. But you put a notebook over that. But you put a paper over that."

And I did that. I own that. I did that on Monday. And so, the work of love isn't as consistent as the storybooks would have us believe that the work of love is this. Some days I'm honest, some days I'm not. In the days that I'm not, I got to sit with myself and uncover why I'm not.

Shamari: Thank you for sharing that. I think it's just a reminder. And this podcast is really all about that, but that teachers are human too. We're humans. We make mistakes. We do. And it's okay. I think the important thing is that we acknowledge them, take responsibility. Think about the consequences those mistakes might produce for our students, sit with ourselves and then reflect, "All right. Moving forward, how might I try to do this differently?"

Cornelius: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Absolutely. And just being open to that feedback, because it would have been really easy for me to say to that young man, "You can't talk to me this way on my zone."

Shamari: Right.

Cornelius: It would have been really easy to dismiss him. Like you go to your next class, "How dare you unmute your mic and speak to me in this way." But I had to really listen, because I had built an expectation of who I am in the institution so he was expecting a certain kind of love that he didn't get from me. And so he demanded it and so many times we told police kids. Because it would've been really easy for me to say check your tone and don't speak to me this way, but so I had to sit with his anger and sit with my mistake at the same time.

Shamari: Honestly right. It's love. And so in thinking about our humanity and thinking about humanity in the fact that we make mistakes and we're super complicated and there so many things that contribute to the way that we move through the world. And that contributes to the way the world reads us as a human who teaches, what do you wish others knew about you and your work?

Cornelius: Two things. I wish that people knew that it is hard for us too. That one of the things that... And I want to know how to deal with it. That people see me, they see us doing the work that we do and they dismiss it. So they'll be like, "Cornelius, you only connect with those kids like that because you're Black too." Or and some logically that'll make sense. So all Black people, melanin just qualifies you to be a great teacher. I would like to say, that's true, but we know that's not. And or Cornelius, you're so brave and so you can do this work, but I can't. And I find those things being just incredibly dismissive, the people don't see the hours that we study or the days that we spend in reflection with our friends or the evenings we spend, crying in the shower because we don't want our children to see us crying in the living room,

And so all of those things it's hard for us to, but we do it because the temporary discomfort of right now is worth the eventual liberation. And I get so upset with people even now, as we watch these election returns come in and I know this podcast is going to air later, but right now, all of the excuse making that people are saying, "I don't really talk to my relatives about politics. I don't really get them to vote. I didn't really talk about Donald Trump's white supremacy at my dinner table because that would've made things uncomfortable." And that we do uncomfortable every day and people dismiss that, "You're just good at it." I'm like, "No, it is just as uncomfortable for me every day as it is for you to spend two minutes talking to your uncle about why he's a racist or for you to spend three minutes with your auntie talking about her homophobia.

And so I wish when people saw the work that people knew that it wasn't easy, but then at the thing at the same time that is not easy, it is also incredibly joyful. Never am I happiest than when I am working with children toward our collective liberation and collective liberation can look like a lot of things. It can look like an argument essay. It can look like an art project that we do in seven period. It can look like the virtual band concert that we're getting ready to have because we can't have an in-person band concert. So collective liberation, depending on the day can look a lot of different ways. And so at the same time that this work is hard, it is so incredibly joyful and meaningful. And for every hardship, it feels like there are 20 resulting triumphs, but learning to measure those triumphs, not in economic terms or not in terms of big awards, but triumphs like Shamari came to school today, that's a triumph or somebody asks to play an instrument today who didn't want to play an instrument last year that's a triumph.

And so learning to measure that, I think people want these big awards or they want this huge revolution. And I'm like the revolution ain't going to be that the white house turns upside down. And all of a sudden it's a place of justice. The revolution is going to be that two kids who didn't want to play instruments last year selected to play instruments this year. And they have found the beauty and the joy of music. The revolution is going to be the kids who didn't feel like they had a voice or something to say, or didn't feel like they have an audience discover that voice and discover that audience with an essay or a poem that they write. And so I am so fortunate that I get to see the revolution every period so.

Shamari: Wow. Wow. I have two final questions. Sit with this present moment, reflect on it, whatever it means for you and your work. What would you say to other humans who teach and who are teaching right now? What would you offer them?

Cornelius: I'm going to move away. So I'm going to use some words in English that have been co-opted into cliché, and I am going to liberate them from their cliché and reframe them in a more radical context. So the words do your best have been stolen from us. That people put them in greeting cards. They use them in this kind of toxic positivity to excuse the deep systemic study that people want to do, but like do your best. And here's what I mean by do your best. I don't mean do your best in terms of follow the rules of the establishment. I don't mean do your best in terms of kill yourself to make ends meet or kill yourself, to meet somebody else's goals. But I do mean do your best in this idea that we know the way, like we knew the way before maps, we knew the way before curriculum, we knew the way before school existed, that I always tell people learning predates school.

So when I think about like what I want people to have in this moment, I want people to understand that the best that this universe has to offer is already in them. And all they got to do is do that. And sometimes the best that this universe has to offer is a smile across the zoom camera at a kid who doesn't have their camera on, but, you know they need it. Like sometimes that's your best. And sometimes your best telling the kids I don't got no worries today. And so we're going to do some projects. We're going to sit in the silence, but right now, there are very few words today, but I have some ideas that don't quite sound as eloquent as I want them to sound.

So sometimes your best is helping kids to see the ugly that comes before the eloquence. Or sometimes the best is calling a colleague and helping them to understand that you can't do it today, you need their support. And so being able to pick up the phone and be like, "Shamari I can't do it today alone. I need you." Sometimes that's the best and so for me, I channel that every day. They're like what is best and best isn't a thing that I do for an institution. Best isn't a thing that I do to meet a certain benchmark or expectation, but best is me taking a full assessment of what the universe is handing me right now and being present with that thing and being fully responsive to that thing and doing that with respect to all of the students that we serve and with respect to our environment and with respect to those yet unborn who are going to come and inherit this legacy after us. So yeah. So do your best.

Shamari: Thank you. Thank you. And so this podcast is called Water For Teachers. And water, for me always brings up things of restoration, healing, relaxation, memory, reflection, nourishment. And so I want to end our conversation Cornelius. With a sort of abstract question, but I trust that you will take it up in a way that makes sense for you. My last question for you is this, what is your water?

Cornelius: I'm a new Yorker. And so I got to answer this in the most New York way possible. And so most people listen to this podcast, won't even understand what I'm talking about. But I will never leave the city and I live in this city because of the energy of this city. I feel like when I am at my most fatigued, just like a walk down the block or a trip to the bodega or sitting on a subway car and just listening to the idle chatter, students, let us up in the car like that energy, that's my water. Every time I think that I have nothing left to give the city hands me something else. And so recently, because we can't be on subways. And recently, because we can't gather in large numbers, my water is riding my bike through the city and just like inhaling the city.

And so I ride from my home in Brooklyn, over the Brooklyn Bridge onto the West side of the West side highway, all the way up to the George Washington Bridge over the George Washington Bridge and into Jersey. And really I don't ride for the exercise that I ride to hear the sound I ride, to feel the pulse I ride to be in touch with my city. And so that's my water and I imagine for those of you who are not in New York, you have to find ways to be in touch with the people. And I think we do this thing as teachers, we're like, "No, but I'm in touch with my students." And your students are a version of the people that show up from 8:00 to 3:00. But I think about the communities that those students represent, I think about the spaces where those students gather.

I remember once asking a school leader who was having a difficult time in her school, I was like, Well, you're having a difficult time and a lot of the Black families don't trust you. So why don't we go visit some of the Black families so that we can build trust that we can go hang out where people hang out and we can go patronize the businesses where people spend their money. And so I asked her as a visitor to her town, I was like, "Where do Black folks hang out in your town?" And she said, "I don't know." And I remember being so perplexed by that. I was like, so you know where people go from 8:00 to 3:00 but after 3:00 people don't exist to you?

You don't know where they go. So how can you teach people if you don't know their realities outside of your school building? And so when I think about, again, my water. My water is inhaling the city, and I hope that wherever you are, wherever you're listening, that I hope that you have the time and the flexibility and the presence of mind to appreciate not the infrastructure of the city, not the urban layout of the city, but the people of whatever city or town or municipality or village you call home.

Shamari: And for those of you at home listening, I'd like to invite you to join the conversation. Take a moment and sit with that question. What is your water right now? Your source of peace or healing, joy, relaxation. If you feel so moved, share your responses with us. I'd like to engage with you and your humanity.

You can tell your responses on Twitter using the #waterforteachers or tag us using our Twitter handle @Water4Teachers. That's the number four, water, the number four teachers. Thank you all for sharing this space with us. Cornelius, thank you for your energy, for your love and your light until next time, everybody in peace and love. Bye

Shamari K. Reid

Shamari K. Reid

I often refer to myself as an ordinary Black Gay cisgender man from Oklahoma with extraordinary dreams. Currently, that dream involves completing my doctoral work at Teachers College, Columbia University in the department of Curriculum & Teaching where I focus on urban education and teacher education. Before starting my doctoral program, I completed a B.A. in Spanish Education at Oklahoma City University and an M.A in Spanish and TESOL at New York University. I've taught Spanish and ESL at the elementary, secondary, and post secondary levels in Oklahoma, New York, Uruguay, and Spain. In addition to my doctoral work, I have spent the last few years as an instructor at Hunter College- CUNY offering courses on the teaching of reading, urban education, and language, literacy, and culture. I have also been engaged in work as a consultant for the New York City Department of Education’s initiative to combat the discrimination students of color face. My research interests include Black youth agency, advocacy, and activism and transformative teacher education. I am currently in the process of completing my dissertation on the agency of Black LGBTQ+ youth in NYC. Oh, and I have small addiction to chocolate chip cookies.

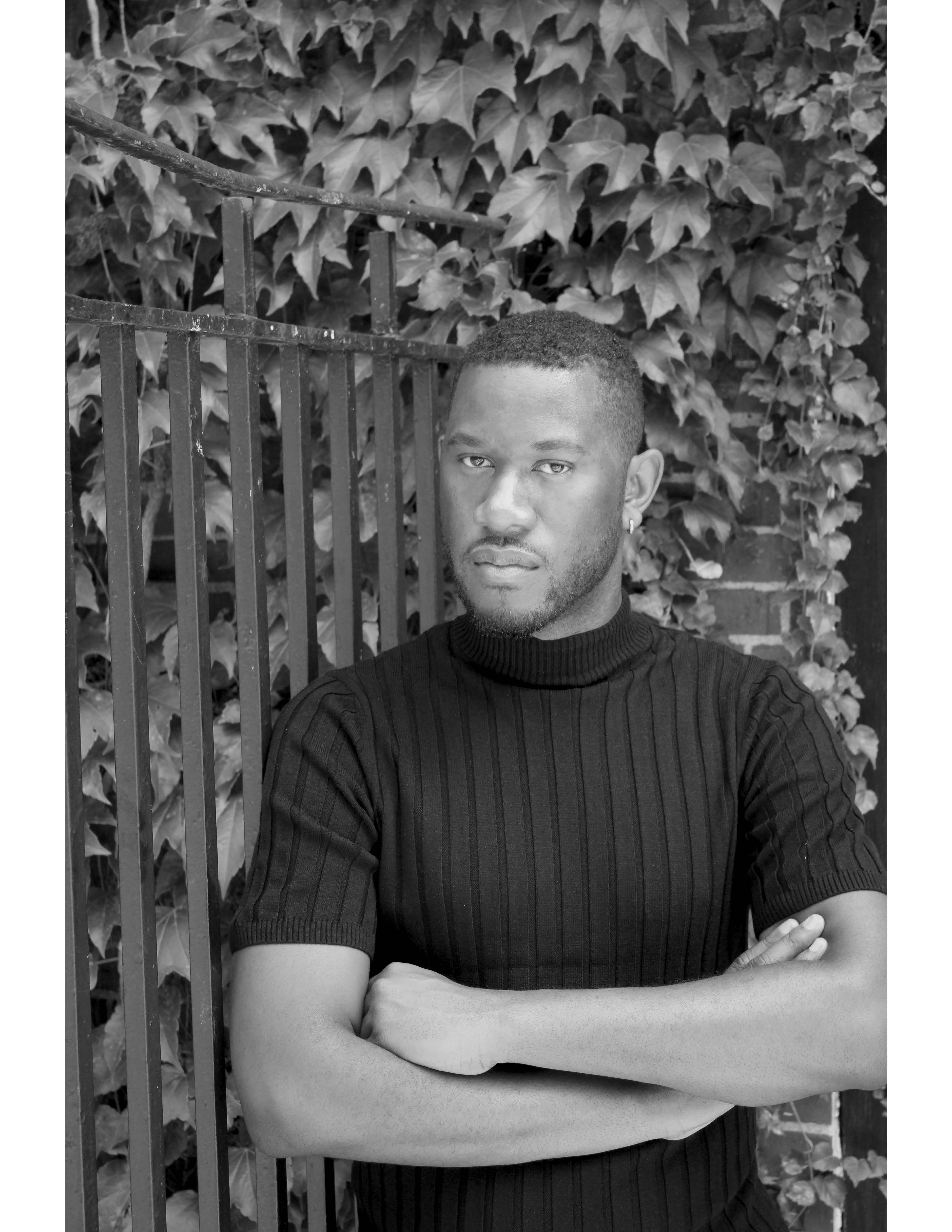

Cornelius Minor is a Brooklyn-based educator. He works with teachers, school leaders, and leaders of community-based organizations to support equitable literacy reform in cities (and sometimes villages) across the globe. His latest book, We Got This, explores how the work of creating more equitable school spaces is embedded in our everyday choices—specifically in the choice to really listen to kids. He has been featured in Education Week, Brooklyn Magazine, and Teaching Tolerance Magazine. He has partnered with The Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, The New York City Department of Education, The International Literacy Association, and Lesley University’s Center for Reading Recovery and Literacy Collaborative. Out of Print, a documentary featuring Cornelius made its way around the film festival circuit, and he has been a featured speaker at conferences all over the world. Most recently, along with his partner and wife, Kass Minor, he has established The Minor Collective, a community-based movement designed to foster sustainable change in schools. Whether working with educators and kids in Los Angeles, Seattle, or New York City, Cornelius uses his love for technology, hip-hop, and social media to bring communities together. As a teacher, Cornelius draws not only on his years teaching middle school in the Bronx and Brooklyn, but also on time spent skateboarding, shooting hoops, and working with young people.

Cornelius Minor is a Brooklyn-based educator. He works with teachers, school leaders, and leaders of community-based organizations to support equitable literacy reform in cities (and sometimes villages) across the globe. His latest book, We Got This, explores how the work of creating more equitable school spaces is embedded in our everyday choices—specifically in the choice to really listen to kids. He has been featured in Education Week, Brooklyn Magazine, and Teaching Tolerance Magazine. He has partnered with The Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, The New York City Department of Education, The International Literacy Association, and Lesley University’s Center for Reading Recovery and Literacy Collaborative. Out of Print, a documentary featuring Cornelius made its way around the film festival circuit, and he has been a featured speaker at conferences all over the world. Most recently, along with his partner and wife, Kass Minor, he has established The Minor Collective, a community-based movement designed to foster sustainable change in schools. Whether working with educators and kids in Los Angeles, Seattle, or New York City, Cornelius uses his love for technology, hip-hop, and social media to bring communities together. As a teacher, Cornelius draws not only on his years teaching middle school in the Bronx and Brooklyn, but also on time spent skateboarding, shooting hoops, and working with young people.

You can connect with him at Kass and Corn, or on Twitter at @MisterMinor