Last fall, I wrote about the Blahs, a predictable time of year when I struggle with energy, motivation, and self-doubt. A friend pointed out that our students battle their own Blahs as well, and that many battle seasonal Blahs, or Blahs that center around certain stressful times of the school year. All it took to confirm she was right was to observe my classes that morning.

Last fall, I wrote about the Blahs, a predictable time of year when I struggle with energy, motivation, and self-doubt. A friend pointed out that our students battle their own Blahs as well, and that many battle seasonal Blahs, or Blahs that center around certain stressful times of the school year. All it took to confirm she was right was to observe my classes that morning.

So, putting the “action” into action research, I took this question to my students. I read my “Battling the Blahs” to my students and asked for their thoughts. Do they experience the Blahs? Do the Blahs come at a certain time? What strategies do students use to get out of the Blahs, or at least cope? And most importantly, what can we as teachers do to support students when they are struggling with the Blahs?

As always, my students brimmed with ideas, answers, and insights. Here are five main themes that came out of their responses:

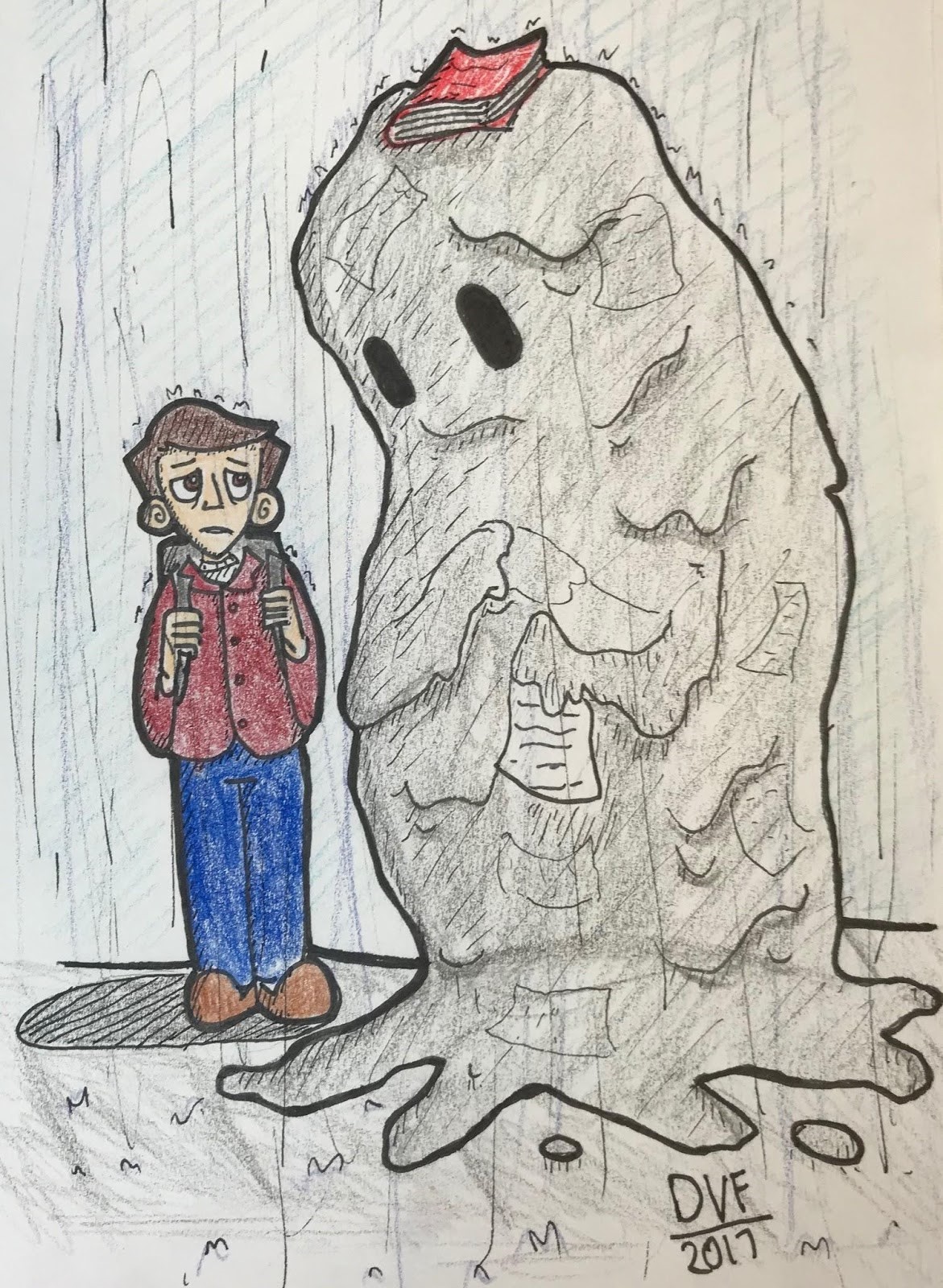

1. Yes, the Blahs are very real to students too, and they can strike at any time. Alyssa, a freshman, wrote, “The Blahs: It’s like carrying a bag of bricks in both hands across a long, frozen lake, and if you don’t get the bricks across the lake in time, the ice will break and you will fall in.” Dimitri, a passionate artist, conjured the Blahs as a looming, messy specter in the accompanying illustration, which he drew in his notebook as he and his group discussed descriptions and suggestions.

1. Yes, the Blahs are very real to students too, and they can strike at any time. Alyssa, a freshman, wrote, “The Blahs: It’s like carrying a bag of bricks in both hands across a long, frozen lake, and if you don’t get the bricks across the lake in time, the ice will break and you will fall in.” Dimitri, a passionate artist, conjured the Blahs as a looming, messy specter in the accompanying illustration, which he drew in his notebook as he and his group discussed descriptions and suggestions.

2. Many students reported a weekly or even daily Blah cycle—we decided to call these low-level but frequent blahs the Mehs. It’s that point in the week or the day when they are just going through the motions, showing up in body but not in spirit. Fifth period, after lunch? Meh. Thursday? Meh.

3. The most frequently cited cause of the Blahs: homework. By far. Leslie, a freshman, wrote, “By the time I get home from practice, I’m exhausted, but I still have at least two or three hours of homework. I feel like homework will crush me.” Many students also wished teachers better coordinated due dates, citing many examples when big projects or papers were due on the same day. Again and again, as I read through my students’ comments, students begged for understanding and a reduced workload. No More Mindless Homework by Kathy Collins and Janine Bempechat offers many practical suggestions as well as research to help us reconsider the why behind the homework we assign.

4. Students often feel just as stressed as we do. They feel pressured from all sides: school, friends, family. They feel their future hanging in the balance, chasing the dream of sometimes unrealistic expectations: a 4.0+ GPA, athletic prowess, club leadership, extensive community service. In her TED Talk, “How to Make Stress Your Friend”, health psychologist Kelly McGonigal shares important research that can help us reframe stress as helpful, explaining that perhaps the most important factor in whether stress is helpful or harmful lies in how we view it. Since I wanted to make sure we had deep discussions about stress, this TED Talk became the first text of second semester for my seniors. Here’s a writing prompt I created as a starting point, which we used after viewing the TED Talk together. And yes, I realize there’s an irony in creating a stress-inducing essay prompt to discuss stress, but all of my students were able to pull rich examples from their own lives and start thinking about how they can reframe their own reaction to stress.

5. Many students struggle with the undertow of powerlessness: where is their personal agency in their education, their lives? If a student claims the pressures of education for themselves, these can function as powerful intrinsic motivation. But if these pressures are imposed upon them, they can lead to anxiety, depression, and, as we have unfortunately seen with heartbreaking frequency where I teach in Silicon Valley, suicide. For me, the drive to include more student choice has been a direct outgrowth of my desire to foster more student agency. This is THEIR learning, THEIR reading, THEIR writing. This is THEIR class, and I am here to help them mine the depths of their own possibility. As the people who have the most contact with young people, we have a responsibility to put our students’ physical and mental well being above all else.

What can we do to help?

Our job as the adult in the room is to maintain perspective, to help students experience the importance of the work we do, while also learning how to care for themselves as people with bodies, minds, and hearts of their own.

When it comes to classroom-induced Blahs, having a break or some fun activity to look forward to seemed to help with both the Blahs and the Mehs. Students suggested brain breaks during classes, getting them out of their seats to do a quick activity.

One strategy I find consistently pays off is a lightning gallery walk. I have nine small whiteboards spaced around my room; each of the nine table groups have an assigned whiteboard. If my students look like zombies, I’ll often figure out a way to translate the lesson into a gallery walk. Sara Ahmed, in Upstanders, calls these in-the-moment teaching decisions “game day moves.”

If we’re reading a mentor text for craft moves, I might assign each group a different paragraph, give them a few minutes to find an example and write it on their whiteboard, and then do a lightning gallery walk, where students get a short time—30 to 90 seconds—at the other groups’ boards so that they can annotate their mentor text with the strategies found in the rest of the article.

This way, students become teachers, as it should be. We accomplish the goal of the lesson, but we do it quickly, interactively. My job is just to stand back, listen, and redirect if students need help.

I suggest you curate your own set of game day instructional strategies to liven up a lesson, to get kids up out of their seats and moving around, or even just talking to one another instead of listening to you. There’s a reason we say “blah, blah, blah” when we recount someone talking too much—it’s boring! I work hard to keep to a rule: I get no more than ten minutes of talking time per period, and less, if possible.

And finally, let’s give students learning experiences whenever we can. My student Katelyn wrote, “Those thirty-six math questions I had to answer for homework last night? I’m not going to remember any of them a week from now. But that marshmallow and spaghetti group project we did in sixth grade? I’ll never forget it.”

On Seniors:

My freshman had so many helpful tips, but I would be remiss not to touch on the topic of seniors. Blahs in freshmen are one thing. Blahs in seniors are entirely another matter.

Timelines are shorter. Stress is heavier. Stakes are higher.

Seniors have more complex lives. Many can drive. Many work. (And many work to support car payments and exorbitant car insurance payments.) And as we know, there’s even a special term for the Blahs that seniors experience: senioritis.

I suggest early aggressive treatment for senioritis. Keep an eye out for the symptoms; talk with students as soon as you notice signs of the Blahs setting in. Help them come up with a plan. If this isn’t enough help, pull in more support: parents, counselors, case managers if the student receives support services.

But here’s the thing: it’s easy to write off some much more serious problems as senioritis, because on the surface they look the same. In my next blog, I’ll explore what happens when the Blahs are hiding the Abyss.