By Michael Pershan

When I was a student, almost all the written feedback I got in math class came on tests. The main purpose of these notes was to justify a grade. This was frustrating to me and ever since I became a math teacher, I’ve wanted to give feedback of a different sort. Rather than reporting to my students what they did or didn’t understand, I wanted my feedback help them come to understand it on their own. Two years ago, I realized that, despite my best efforts, I was falling short of this standard. Since then, I’ve been searching for better ways to use comments to help learning along.

There is a type of feedback that I completely disavow. I call it the “better-luck-next-time” comment. I recently gave feedback of this sort, and I kicked myself for it. I was meeting a student out of class to return a quiz. We only had a moment, but I couldn’t help myself. “So you see how, for this question, you added these two numbers? You should’ve multiplied. Do you see why?” He said he didn’t know why, so I explained why, and he thanked me and walked away. Better luck next time!

The problem with “better-luck-next-time” comments is that feedback, passively received, does not lead to learning. Thinking about critical comments can be hard work for anyone, and our students often let our feedback pass without reflection. This is where teaching—the art of helping others have great thoughts—comes in. Feedback needs to be part of teaching, not an add-on to it.

—

I try to make sure that students think about the comments I give them.

—

In-class revisions are one way that I try to make sure that students think about the comments I give them. It’s a simple but sturdy classroom routine: I hand back your paper with feedback, and your job is to read the comments and improve your work. It’s a routine that, more often than not, works wonderfully in my math classes.

It becomes clear very quickly, though, when one of these revision sessions is not working well. My first clue is when a student has called me over (“MISTER PER-SHAAAAAN”) before I’ve even finished handing papers back. Usually the voices multiply, and soon there’s an entire chorus of students calling my name. From then it’s a mad dash to figure out where I had gone wrong, and if the session can be salvaged.

After one of these frustrating revision sessions, I started flipping through my planning journal. (In case of a fire, first comes my wife and kid. Once they’re safe, I’m going back for my journals.) I started searching for patterns. What was I doing differently when things went well? Why were some of my revision sessions flopping so badly?

As I went through the past entries in my teaching journal, I noted that revisions worked much better if I started with an activity with the entire class before giving feedback. These activities were relatively short—ten, maybe fifteen minutes long—and were attempts to put the feedback in context. Usually I did this because, when I started to write comments, I realized the comments wouldn’t make sense on their own.

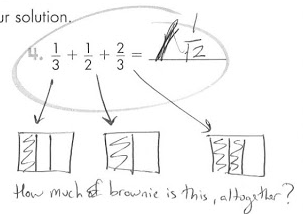

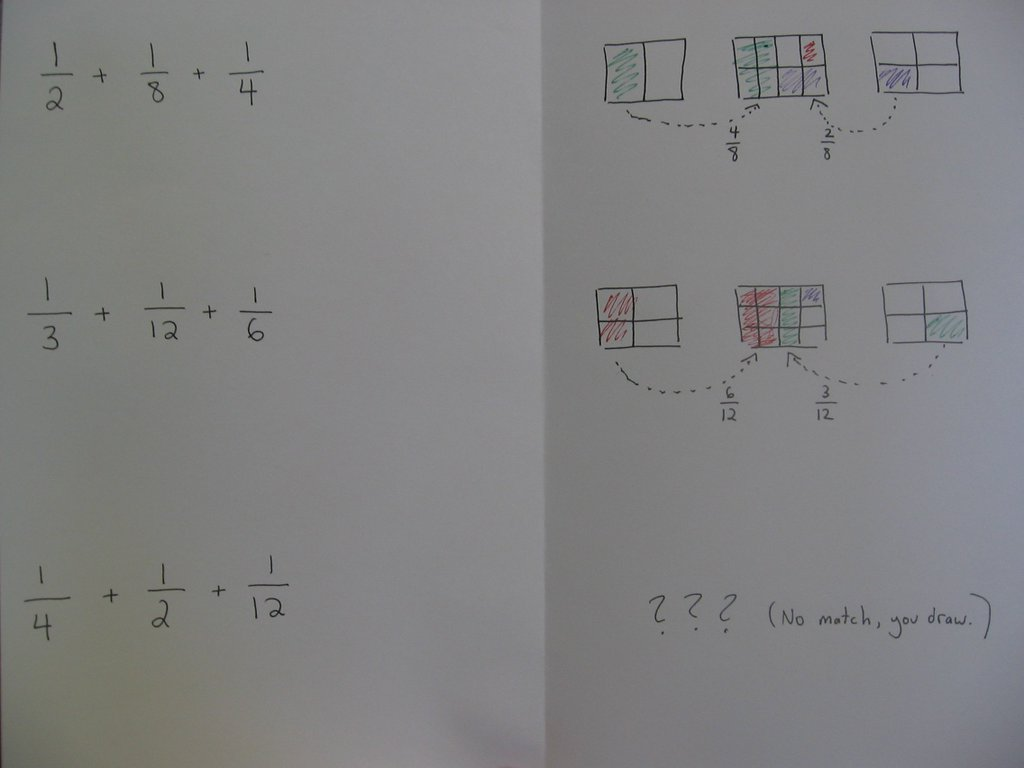

So, for example, before giving this comment to some of my 4th Graders...

...I asked my entire class to think about this matching problem:

When I returned their papers, nearly all my students were able to use my comments to revise their papers. Of course, some students weren’t sure where they had gone wrong. Since so much of my class was able to make sense of their work, I was able to give the students who were entirely stuck (“MISTER PER-SHAAAAN”) the time and focus they needed.

Comments have strengths, but they also have limitations. Comments direct attention. (“Hey! Look at your work over here. There’s something to notice.”) What I’ve learned, though, is that comments aren’t particularly good at building understanding all on their own. If students are going to learn to visualize fraction addition in a new way, they usually need specific kinds of help—questions to think about, chances to discuss, time to make mistakes and learn from them—that outstrip what a short comment can provide.

As part of my research as a Heinemann Fellow, I’ve developed a longer, more integrated feedback routine. The routine starts when I’m looking at student work, and I notice there’s something that my students are ready to learn. Then, I design a short activity—about ten minutes, ideally—that will focus on this new idea. When I’m ready to hand back their papers, I’ll ask students to work on the short activity in class. The activity and the comments work together. (I’ll even work backwards—what is the comment that I want to give? What experience would my students need in order for that comment to be meaningful?) Then, in class, after the activity is finished I hand back students’ papers with comments and ask them to revise their work.

This is the opposite of better-luck-next-time feedback. It’s not treating feedback as a seasoning (an add-on) or as magic (the more the better!). Comments can’t develop conceptual understanding on their own—this sort of feedback only makes sense as part of a larger bit of instruction.

Feedback comes in so many forms. “Comments for revision” is one; surely there are many, many other ways of using feedback out in the world of teaching. In order to see them, though, we have to look past the feedback itself, and pay special attention to what comes before and after.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Michael Pershan is a math teacher at Saint Ann's School in New York City. His action research question asks, "Is written feedback or oral feedback more beneficial for fostering geometric thinking in high school students?"

Follow Michael's progress on Twitter.