The following is an excerpt from Four Essential Studies: Beliefs and Practices to Reclaim Student Agency, by Penny Kittle and Kelly Gallagher.

Belief #1: The five-paragraph essay is a problem now

Because formulaic writing is valued in standardized testing, teachers are in a tough spot. On one hand we want our students to do well when the tests are used as gatekeepers for advancement. Teachers and schools are judged by these scores. Standardized tests still exist as one factor in the admissions process for many colleges and then for scholarships to help pay tuition. Many private schools, charter schools, and even some public high schools use standardized exams to determine who gets in. If that process includes timed essay writing, a formula can help students manage the anxiety with a simplistic structure for their thinking. Students want help passing these tests. We recognize this. But we should also recognize the irony here: although performing well on standardized tests might help students get into college, repeated practice of the standardized form makes them ill prepared as writers once they are admitted.

Students are not challenged by five-paragraph-essay (5PE) assignments on books they most often have not read. Writing the same exact essay year after year (and across the curriculum) teaches them that writing is simply labor, not the opportunity to look more closely at the parts of something big and dig deeply to understand them. Formulas have kept them away from real challenges. College freshman composition teacher John Warner argues in Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities,

Current common approaches for teaching writing are simultaneously too punishing and not nearly challenging enough. Part of the problem is how “rigor” is viewed in education. “Rigor” means “strictness” and “severity.” It is an artifact of a different time and a different mentality toward schooling. It remains popular mostly as a way to invoke days of yore that are supposedly better than today. . . . When students say a class was “hard,” they often mean “confusing” or “arbitrary,” rather than stimulating and challenging. (2018, 142)

We would add the following to the list of arbitrary and confusing approaches to teaching writing: rules that demand paragraphs will contain five (or nine or whatever) sentences; the topic sentence will always be first in each paragraph; and the thesis or claim must always be directly stated in the introduction. These rules do not represent excellence in writing. On the contrary: in many cases, adhering to them wrings the goodness out of writing. The writer is punished by being shoehorned into a form. Peter Elbow, noted writing researcher, argues that “the five-paragraph essay tends to function as an anti-perplexity machine” (2012, 308). Katherine Bomer agrees, adding, “There is no room for the untidiness of inquiry or complexity and therefore no energy in the writing” (2016, xi). Not only is energy drained from the writing when students practice mechanized thinking, but students also lose the valuable practice of generating and organizing ideas. When the form is predetermined, much of the writer’s important decision-making has already been stripped, which is one reason Penny is now encountering so many college students who believe they cannot solve their own writing problems.

We agree with John Warner’s notion that approaches taken by writing teachers are “not nearly challenging enough” (2018, 142). The form does the thinking for the student, and the student simply plugs in and follows. Without an understanding of options, students can’t imagine how a different form might better engage an audience or how changing the structure might better communicate their ideas. Teachers in high school rarely (if ever) meet across content areas to consider how often students are writing the exact same formulaic essays. The teachers at our schools never met to have these discussions. Students need numerous opportunities to study the various forms an essay can take, and they need repeated practice experimenting.

This is not our only objection, however. The lack of student decision-making and agency is compounded when students are constrained by the teacher’s choice of subject and the lack of an authentic audience for their writing. We like how novelist Lily King explains the problems with standardized essays about books:

While you’re reading [the book] rubs off on you and your mind starts working like that for a while. I love that. That reverberation for me is what is most important about literature. . . . I would want kids to talk and write about how the book makes them feel, what it reminded them of, if it changed their thoughts about anything. . . . Questions like [man versus nature] are designed to pull you completely out of the story. . . . Why would you want to pull kids out of the story? You want to push them further in, so they can feel everything the author tried so hard to create for them. (2020, 271)

Beyond the literary essay, consider the ways student voices are amplified today: blogs, podcasts, voice recordings, YouTube videos, TikToks, Instagram stories. Audiences demand variation in structure and style. A blog written for skateboarders is going to look and sound different than a TED talk created to explain the coronavirus. But ask yourself how long you would read a blog or listen to a podcast that began like this: “Today, I will discuss X and give you three reasons why I believe this to be true.”

Please.

We are already dozing off. No one writes like this outside of high school. No one.

How did this mismatch of expectations between what we hope for young writers and what they repeatedly practice happen? We suspect it has a lot to do with the fact that K–12 teachers have too many students, have too little time, and are required to prepare their students for too many mandated standardized tests. In the rush to plan, assess, and respond to the chaos of needs throughout the school day, we have been seduced by a form that is easy to teach and easy to grade.

But let’s be honest: we can grade an entire stack of 5PEs without really reading them— which might be a good thing, because after closely reading a few of these lifeless essays, we would rather get up and go scrub the bathroom. We understand the very real time pressures put on teachers, but teaching the essay as a vehicle of discovery and understanding does not take any more time. It does, however, take different intentions, different lessons, and new practices to increase feedback to students while they are drafting.

Belief #2: The 5PE is a problem later

One of our mentors, Sheridan Blau, deepened our thinking about how the 5PE is a mismatch for college. Speaking at the University of California, Irvine’s Writing Project annual conference in 2019, Blau said: “A university is a knowledge building community, and the writing for that community is an exploration of concerns within the field of study, a meditation on what a professor is learning, or questions that do not have answers” (italics ours). Blau, who now teaches at Columbia University, reminds us that essay writing is preparation to enter conversations that will occur in class. In addition, the college essay is not a summary of what a text says, but an exploration of how the student responds to the ideas there. Students are expected to put their thinking in dialogue with the ideas of an author and to demonstrate how carefully they have considered that work. College professors expect students to make decisions about organizing their writing and, by the end of the semester, to frame their ideas into five- to ten-page papers exploring questions that lie at the heart of each content area. And they expect this from first-year students.

Penny’s college freshmen began their first week of classes feeling (mostly) prepared. They had practiced survival skills in high school to emerge with the grades to get into a university. However, they had invested little of themselves in their writing and, frankly, lacked the experience of developing their own ideas beyond a few paragraphs. These freshmen expected to find assigned topics, templates, and rubrics at their university. They didn’t. They were told that the five-paragraph formula they had relied on for success in high school courses was not college level writing. The students’ sense of betrayal (and fear) was real.

Take Jillian, for example. In one course, she was assigned the following: “Identify an idea or challenge in the world (e.g., mass incarceration) and contribute your thinking to readings which will be discussed in class. Respond to the author(s) as you shape your thinking.” In Figure 1–1, let’s look at the expectations for her research essay alongside the decisions she’d have to make.

There were a lot of big decisions that needed to be made here. This process is not specific to this one assignment, however. We think of another former student, Abby, who was assigned to write four essays on the following topics in her first-year composition course: identity, family, place, and “It was as it shouldn’t be.” That’s it. No additional information or prompts. The students could interpret those ideas in any way. There were no specific guidelines other than each essay had to be at least one thousand words in length. No rubrics. The professor identified great sources of essays but left the students to explore them. The first one was due the next Friday. Go.

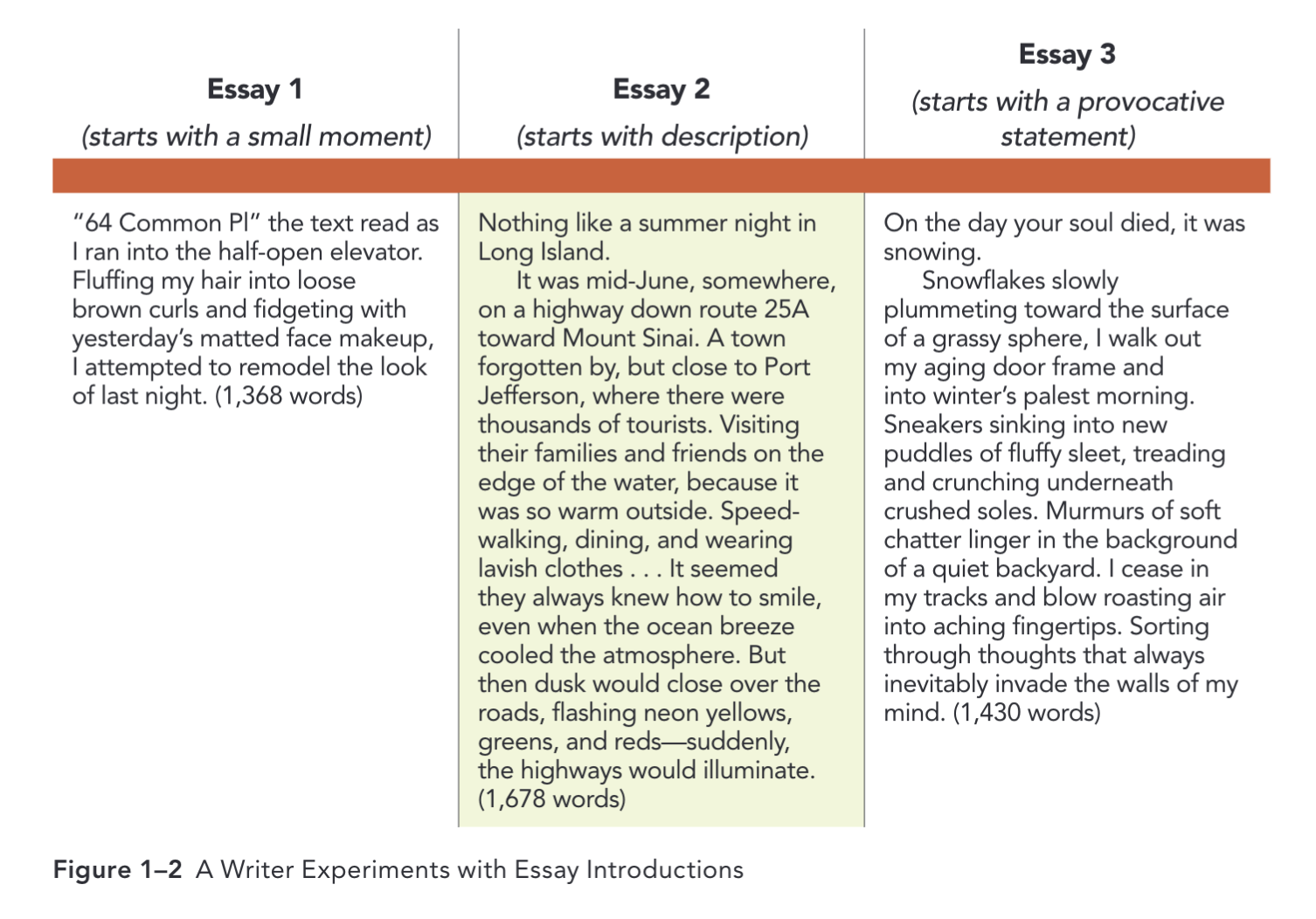

Figure 1–2 contains the introductions to three of Abby’s essays, each approached differently. We are struck by her voice—how these essays begin by breathing her individuality.

Beyond Abby’s introductions, we notice numerous other interesting decisions she makes. In her first essay, she recalls her father’s fondness for Joni Mitchell’s song “Both Sides Now,” and much later in the piece she weaves in some of the song’s lyrics in a way that lends the essay a deep poignancy. In her second essay, she weaves in an original poem in the midst of her prose. In her third essay, she begins with a lengthy flashback before transitioning back to the present day. Abby is not writing to adhere to a set of rules put forth by her teacher; she is experimenting with form in search for the best way to say what she wants to say—what she needs to say. Her essays vary in length because she’s written until she has completed her thinking on a subject.

Abby believes she learned to write well in two semesters of an elective poetry class in high school. Each of her poems began as an experiment: What’s the best way to write about this? There was freedom to play with thinking in her notebook and time to share her fumbling starts with peers. Now in college, her individual sentences ring with expertise:

Night has fallen and is swirling and twirling around me.

Gold chains hang across his neckline like trophies against a prize.

The fine oil paintings and white pillars line sunken walls. It is a life filled with artificial riches, swishing like change in a pocket of hope. And the noises it made rustled in our dreams.

Abby writes with verve and authenticity. Jillian, the same age, is sitting in a first-year college classroom without the skill set to make the decisions expected of her. And we know this: students get to Abby’s level of essay writing when they’ve experienced a lot of practice in struggling with generating ideas and organizing their thinking. The road to excellence is rife with trial and error. It is up to us to entrust our young writers to wrestle with their decisions. Doing so matters now. And later.

Learn more about 4 Essential Studies at Heinemann.com.

Kelly Gallagher taught at Magnolia High School in Anaheim, California for 35 years. He is the coauthor, with Penny Kittle, of Four Essentials Studies: Beliefs and Practices to Reclaim Student Agency, as well as the bestselling 180 Days. Kelly is also the author of several other books on adolescent literacy, most notably Readicide and Write Like This. He is the former co-director of the South Basin Writing Project at California State University, Long Beach and the former president of the Secondary Reading Group for the International Literacy Association.

Penny Kittle teaches freshman composition at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire. She was a teacher and literacy coach in public schools for 34 years, 21 of those spent at Kennett High School in North Conway. She is the co-author (with Kelly Gallagher) of Four Essential Studies: Beliefs and Practices to Reclaim Student Agency, as well as the bestselling 180 Days. Learn more about Penny Kittle on her websites, pennykittle.net and booklovefoundation.org.