Welcome to Water for Teachers, A Heinemann podcast focused on engagement with the hearts and humanity of those who teach. One thing we know for sure is that teachers are human. They have fears. They've experienced tragedy. They struggle. They are affected by crises and pandemics. And like everyone else, they deserve to lead lives full of peace, joy, and love. Join host Shamari Reid and other educators as they move from logic to emotion, from the head to the heart, from thinking to feeling, and from the ego to love.

This week, Shamari is joined by Holly Jordan, a public school teacher of fifteen years from Durham, NC, as they explore the power of vulnerability and being honest about our imperfect humanity.

Below is a transcript of this episode.

Shamari: So, hi everybody. Welcome to episode one. I feel so full right now because this journey to this podcast has been incredible. But here we are, getting to engage with the heart and the humanity of a brilliant human who teaches, Holly Jordan. But before I speak with Holly, I want to start off today's episode with a letter. After, I'll invite Holly to explore any and everything the letter brings up for us, both. The letter I'm going to read today is one written by a high school student to her former third grade ELA teacher.

A letter to my third grade teacher. I used to dream of becoming a writer up until your class. I remember when you told the class, to bring in a book from home for silent reading. I remember how my father used to bring home books that the children of his coworkers outgrew. I remember finally finding the perfect book for silent reading and eagerly packing it into my backpack the night before school. I counted down the seconds until silent reading and I carefully placed my book onto my desk making sure not to crease the edges. You walked around the classroom, praising the book choices of others. I grew excited as you approached my desk. I knew that you would be impressed with my book. I remember how you approached my desk and took a quick glance over at my book. That book is not right for you. It's too advanced. Pick out a book from the library in the back.

I used to dream of becoming a writer up until your class. What you did not know was that I come from a family of immigrants. My family had to learn English together. Our English consisted of the words my father picked up from his early job as a bus boy. Our English consisted of the words my mother gathered through her small interactions with our neighbors. Our English was the English my two older siblings brought back home from school. At a young age, I pushed myself to learn and perfect the English language, as best as I could. I made sure to read any book that I had access to. And I practice my reading as much as possible. I slowly developed a love for a language that was once foreign to me. However, your words made me feel as though my efforts were not good enough. I used to dream of becoming a writer up until your class.

Now, I want to invite Holly to engage in a conversation with us. Holly has been a public school teacher for 15 years. All of them at the same school in Durham, North Carolina. This year, she teaches English and advisors the gender and sexuality alliance. Holly describes herself as an active learner and teacher of racial and social justice, both inside and outside of the classroom. Welcome Holly. Thank you for sharing this space with us.

Holly: I'm really honored to be here. Thank you so much, Shamari.

Shamari: So I definitely have thing that I want to explore with you, but first let me just open the space and invite you to share anything that's on your mind, on your heart after listening to that letter.

Holly: Yeah, that letter was heartbreaking. And what it reminded me was honestly something I think about pretty much every day in the classroom, which is that each of our students are individuals. And there is so much going on behind the scenes. And that's hard to remember sometimes in a room of 30 or more students in a long, long day. Or in this current environment, in a Zoom classroom full of black boxes.

Shamari: Yeah.

Holly: But yeah, what that letter made me think about was that my students are individuals bringing things into the classroom. And I, as an educator, am an individual bringing things into the classroom on that day as well. And sometimes we meet and those things mesh. And sometimes we meet and those things lead to heartbreaking moments.

Shamari: Yeah. I'm so sort of... I don't know, like it's calming to hear you say that we are educators who bring things into the classroom. Because I started this podcast with this desire to have this space where I could engage with other humans who teach other imperfect humans though. Who take our job seriously, who try and work very hard, but who as humans, make mistakes. And I wanted to talk with you specifically, around this idea of imperfection and vulnerability. Because your someone who is vocal about being a white woman who teaches in a school that historically has served a large number of Black students, right. And navigating that and what that means as someone who wants to get it right, but who is aware that we make mistakes, mistakes that could hurt those we serve.

And so I want to just go to a tweet and talk to you about this tweet. You retweeted this by the way. So I hope you remember. And you said this, your retweet said, teachers, you are not heroes and you are not rock stars. You are teachers. Being a teacher is like a really good thing. When we pretend we are something other than what we are, we belittle what we actually do. Normalize, just being a teacher. It's really a good thing. And so I want to ask you Holly, if you could walk us through a moment in which you realized that you're not superhuman, that you're a human who teaches, who is imperfect, and who will make mistakes.

Holly: Yeah. Man. I mean, there are so very many moments of imperfection. And I guess one sort of moment in time that stands out to me is a class I taught several years ago. For most of my career, I taught three preps a day without repeating preps. And that's difficult planning wise. I know some teachers have way more than that. But for me, that's something that I value because of the classes I get to teach. But it also means that there's a lot of planning time.

And one semester I ended up being given a course that I had never taught before, literally a day and a half before the semester started. I just have so many memories of that semester because I had to accept imperfection from myself every single day. Because it wasn't possible with the hours in the day that I had, with the other classes I was planning, with the fact that I am a human being who needs to do things that aren't teaching related sometimes. I would do what I could, but after an hour or two hours of planning a 90 minute lesson, if I do more than that, it was just taking over my life.

And so I was really just underwater that whole semester. And I would feel, I felt so much... I really had to work through the guilt that I felt. Because I knew that my students deserved better in terms of the content, the class content that I was providing them. But I also knew that every day I walked in there and I created a space that was welcoming, and inclusive, and made students feel good to be there. And sometimes the way I was teaching 1984 and other texts that this was my first time teaching, I couldn't even swap them out for texts that I really wanted to teach because I didn't have time to plan all of that.

Sometimes the lessons I was bringing weren't as innovative or anything like that as I wanted them to be. But I could walk in and feel good about the relationships that I was forming, about the goals that we set together and work towards. But it was just, it was very hard for me as someone who really believes that my students who are almost entirely Black and brown, deserve the absolute best. And way more than the world frequently has to offer them. And in that moment, I couldn't do it on my own. And so I had to offer them what I had.

Shamari: When did you or how did you get to a space where you could acknowledge that, forgive yourself for it, and move forward?

Holly: That is a great question. And I think one of the answers there, this takes me back to another moment. I remember this had to be maybe second or third year when things were still really hard. I was still really learning. And I was having a rough day just in terms of feeling like nothing I was doing was working. And I had a student walk in and she was wearing a shirt that said, it's not that serious. And for whatever reason, that resonated with me that day. Because something I really hold to be true about teaching, is that it deeply is that serious.

Our work is very serious, but if we ever think that without us in a particular moment, that the world's going to end, that our students' lives are going to blow up, that we are the saviors. And especially me as a white person, I'm not wanting to be a white savior for my students. That's not an appropriate relationship to hold. So I think it was finding that balance that, yes, this is very serious work, but I am not the end all be all because that centers me. And in a classroom, if I'm centering me, something's off. That's wrong.

Shamari: Yeah. I love that you say that because my first year I think I told myself the exact opposite. I am it. I am Superman. I can do everything. I don't need a lunch break. I don't need to... X, Y, and Z, that I will always be perfect. And I think to admit that I made mistakes, it takes a certain level of like vulnerability to admit that we as teachers are human and imperfect and we'll make mistakes, which is why the letter I started with isn't really to vilify teachers, but to talk about a mistake, to talk about maybe it was a long day. The teacher didn't, I don't know, realize or recognize, but those mistakes do hurt. And I think back to my first year and trying to be so super, and I was so full of myself, I did something that it took me forever to forgive myself for, but I thought I would encourage my students by trying to move them all from grades that I thought were too low for them to As.

And so what I did, I'm like so embarrassed. I wrote each period on the board and I put the number of As each class had, the number of Bs, the number of Cs, the number of Ds, and the number of Fs. And I would circle the Fs and I would tell them you're only as strong as your weakest link. And I thought I was encouraging them. I thought what I was doing was positive, but now I can look back and only imagine how much shame and embarrassment I probably caused some of my students, those who had the grades that were lower than I thought they should have. I also had to unlearn that grades aren't always a direct measurement, if you will, of intelligence. And there could have been something else, but it took me years to forgive myself for that. I felt like a terrible person to say, like you made a really big mistake. And I never got to apologize to them, but if they're listening and they come across this, I'm sorry. I am sorry that I made that mistake. And I understand that me saying sorry doesn't remove the pain they may have felt. But yeah, we mess up.

Holly: Yeah. Apologizing to students is so valuable. It's such a valuable skill. I remember apologizing to a class last year after we'd had a guest speaker in class, and I really felt that the class was being just sort of rude and dismissive to this guest speaker. And that really raised some feelings for me because I didn't want that guest speaker to feel like their time was wasted or to form any opinions about my students. And what ended up happening was I held a restorative circle with my class in order to kind of work through how I was feeling frustrated and hurt. And I know they had reacted in that particular way for a reason.

And they were honest with me and they said, "Ms. Jordan, this speaker was, one, boring." That was true. "Two, speaking down to us in certain ways." And when I looked back upon it, I could see that. And I could see the reasons that they detached from what was happening. And I apologized for my anger because they were right. Like they had seen something that I couldn't see in that moment, because I was so clouded with like embarrassment of what are people going to think. And those moments are really powerful, and I think model something for young people that they need in their lives just as each of us needs it.

Shamari: Yeah. But I think the important step, at least it was for me, is recognizing that you messed up. Like I can only apologize after I accepted that I wasn't Superman. And I think that's what broke me is because I had been prepared and told for so long, especially as a Black man, right? Like, "We need you, you're going to come and do so many wonderful things and you're this and you're that." And there's really a scarcity of Black male educators and all of these things. I thought I was like so special and I still feel that I'm special. But what I had to learn was that I'm not any better than anyone else. And that as a human, who is imperfect, I can make mistakes. Even as this guy who has been sort of regarded as the one who's going to come and turn things around, but like it broke me.

Like I was crying when I realized, "You messed up. You actually made a mistake, a really big mistake. And oh no, there could have been others and you will continue to make mistakes." And so I wanted to ask you how you navigate that in your identities as a white woman who navigates like anti-racist teaching and teaching predominantly Black and brown students, and this idea that people say you will make mistakes and you will... How do you navigate that? How do you hold that truth and the truth that you want to do your work in a way that honors the promise to the educational equity that these students deserves?

Holly: That is such an important question for me personally, because in my journey as an anti-racist educator, I started out without that intention in my career. I started out as a 22 year old woman fresh out of undergrad coming halfway across the country to teach in a place that was new to me at the only school that had offered me a job. And so, I came in feeling like, okay, well, God or the universe has put me here for a reason. So I must be like an answer for this place. And I figured out within a week that I had all of the things that I thought were answers and that I thought my students needed were completely wrong.

Shamari: Yeah.

Holly: And so then, it was a process of rebuilding. The first thing that I did, and I think the thing that has carried me through 15 years of becoming a better educator and an educator who strives to be anti-racist was listen. And listen to my students. And more importantly, even believe them and believe that their experiences are valid, that their emotions are valid. The way they're responding to me is valid. And really learn from those moments. And I think back with a lot of deep shame and embarrassment about some of the microaggressions that I perpetrated both toward my Black and brown students and also my colleagues with all the best intentions, but intentions and impact were not the same thing. And I strive to do better every day.

And now I look at white teachers in my school building who are new to the profession, and I have to remind myself to have that patience with them because I'm clear that I didn't know anything and that I caused harm. And there are certainly still moments that I cause harm. And I think that it's about growth. That incremental growth is healthy for humans and for teachers. I think it's about listening and learning and humility. And I recognize that all of that is so much more complicated in the racialized frame of so many white women in predominantly Black and brown schools, because every moment of harm matters. And I think that like we're talking about today, teachers aren't perfect and need space to grow and learn. Because if I hadn't had that space, if I hadn't had that space, I wouldn't have even been hired in the building that I've worked in. And that has been home for 15 years where I've learned everything that I know about anti-racism. But it's the starting point of all of that for me.

So I think the balance is very complicated. I don't have the exact answer, because there isn't one about like, where's the line? But I do think if there is some sort of line, it is where teachers are willing to be humble and to listen and learn and grow and know that they have to do that. And I'm grateful that I, in my first week of teaching, learned that I didn't know anything and that I really needed to grow. And I think that is where any teacher who's starting out needs to be and remain. So I think ultimately, what worked for me as an imperfect learner was centering students. I think that's basically always the answer, but by really listening to them and believing them and learning from them, because they are experts in their own lives. That is what has helped me grow and learn in my journey as an anti-racist educator. And that to me always has to be central. The students have to be central.

Shamari: Yeah. So as we think about your journey and your growth, you and I talked briefly sometime ago about hard lessons, right? And you've shared that one of the lessons that took you the longest to learn was what it looks like to love yourself. Do you see any connection between self-love and the ability to be vulnerable and accepting our imperfections as humans who teach.

Holly: Yeah. Certainly there is a connection. I mean, one of the things that is great and also hard about teaching, is that students will call everything out. They'll call you out and they will see right through you if you are not being real. It has to be eight years ago that a student said to me, "Oh, Ms. Jordan, is that chalk powder on your face?" "Oh, no it is it." I mean, mostly even at the time, it was pretty hilarious. One thing that I often say to pre-service and new to the profession teachers, is you have to really be comfortable in a lot of aspects of yourself, because students will in their less together moments take advantage of those things. And that's not just students, that's everyone. That's how harm happens in the world.

So for me in a journey of self-love, what that has really meant in the classroom, is a couple of things. One is an increased sense of confidence that both the contents I have to offer, the framing of that content and the extra advice that teachers are always doling out, is grounded in a reality that's really working for me. And so I feel honored to be able to share with students. Frequently, when students come to me for advice, I openly talk about seeing a therapist and what I have learned from that therapist. When students come to me for relationship advice... Which of course happenes sometimes. I had a 45 minutes zoom call earlier this year on this very topic. I am open about the relationships I've had in my life that have ended and what I've learned from that, and what I've taken from that. I just truly believe that if we as educators know ourselves, we're going to bring more authentic life changing and world connected education to our students, both content wise, but also all the other things we're teaching students just by our presence.

Shamari: Yeah. Does teaching ever make you uncomfortable as you think about your work and what you have to do and the students you get to serve?

Holly: Yes. Teaching, it's just hard. It's hard. I actually very often at this point in my career feel great comfort about being in the classroom with my students, even when it's the zoom classroom. But what swirls around all that, is the other parts of being an educator. It's the bureaucracy, it's the things being handed down from administrators, it's the paperwork, it is the professional development that takes time and takes energy, but it doesn't give much back. And those moments are unfortunately often large enough, that they impact what I'm able to bring to the classroom, and the energy that I want to attempt to bring to the classroom. And they unfortunately sometimes cloud the vision of my students and what is actually valuable to me about this work. And that's something I think about daily, and that I have spent all 15 years of my career thus far working through. How do I protect my mental health, my wellbeing, my energy for the things that actually matter? So in that way, teaching makes me uncomfortable.

Shamari: Now we're teaching during a pandemic, what would you say has been the hardest thing for you about teaching and living during these times?

Holly: I would say what has been hardest about teaching and living in a pandemic, is that I am someone who values structure and routine, and it has been knocked over and out, just over and over again since March. I remember, I guess it must've been late March 2020, basically we went out of school in mid-March and had a two week early spring break. I think a lot of districts did that hoping that magically we would be going back in April. Our original time out of school was set to be two weeks. At the end of that two weeks when it was clear we weren't going back I had what was actually the first of a trillion now zooms with students.

I had a call with my whole AVID senior class, who I had been with for three years, and got to see their faces and check in with them. And that's mostly what the call was. It wasn't about content. It was about how are you? How are you handling this? And I got off that call and I just bawled, because this was just so far out of the comfort zone and out of my routine. And just the shock of not knowing how emotional it was going to feel to see their faces, and understand what they were going through. And so I think there's just been moments after moments like that of, "Oh, we're going to go back in a month." "No, we're not."

Now it's the fall and suddenly we know how to do virtual learning more intensely. And so now you have this schedule, but you also have six hours of meetings via zoom that aren't about classes. I have done a lot of work in my regular school life to understand the routine of it, and one thing that I think is valuable about staying in one place for so long, is that I can understand certain things and know how they're going to go, so I waste less energy and that's not true this year. Everything we've been learning.

Shamari: Thank you for saying that. I feel like I'm not alone. I was like, "Am I the only one being rocked by this pandemic?" It really upset me because I read this book, or what is it... A New Earth, Eckhart Tolle and talks about being fully present, and being okay with not knowing, and I read the book and I was like, "All right, I got it." I'm fully present, and I'm okay with not knowing, I can handle uncertainty. Then the pandemic comes and I can't handle it. I cannot handle, I freak out, I don't know what's going to happen. Are school is going to be open? Are they going to close? Are my students being affected? Are they losing loved ones? All of that uncertainty, it terrified me.

I spent 48 hours under my covers in the dark terrified of this. Here I was, I thought I had mastered this being fully present thing and this being okay with the unknown, but I can't. I'm a structure routine guy. I really am and when you take that away from me, I just don't know who I am. So this pandemic has done that. So thank you for sharing that I felt like I'm not the only one who is comfortable with structures and routines.

Holly: Yeah. And I've definitely encountered students in the last several months too who are having that same issue. I have so many students coming in saying, "I don't have the motivation to do anything." I try to straight up say to them, "I am right there with you." And what that is, is depression and anxiety related to this pandemic. I'm not going to diagnose anyone, I'm not going to diagnose myself, but I need my students to know that that is a natural reaction to what is happening this year. And I think one thing that has been really hurtful for both teachers and students is that districts are... And in just the whole country, too many people are acting like we should just be able to jump into this new reality, and it's fine. And it's not fine.

And I think teachers know that very deeply. We completely recreate everything we've done. And I think something that some teachers are missing, is that it's the same for our students. My students are juniors and seniors in high school, they have been taught how to learn one way for their entire career in school. And now after 11 years of that, they're being told, now you're going to do it this way, go. And there has not been the support there for them. As a teacher, I'm trying to provide that support, but I wish there were more structural things in place that were doing that as well, because that's not easy for anyone.

Shamari: Right. Right. And there are just so many misconceptions about our work. And even in a way, I feel that's dehumanizing to expect us to be able to take a weekend and bounce back and have everything transitioned to remote instruction. That is wild to me. And as a human I'm just like, "No, I'm also affected. I'm also tired. I'm also losing people. And so, I need time to mourn and grieve. And you want to give me two days to turn 15 years, mind you, 15 years of curriculum that you've built and adapt it for an online space? That is dehumanizing." And that is why I think, for me, this podcast is so important and it's like, "We are people, you cannot treat us like this. You cannot treat us like robots. We need time too, we need care too." And so I wanted to ask, as we think about misconceptions as a human who teaches, what do you wish others knew about you and your work?

Holly: Well, what you just said brought to mind is this narrative around teachers, but I think a lot of people think is flattering, which is that teachers are superheroes. The teachers and the shirts that say, "I teach. What's your superpower?" Or I saw another meme going around Facebook or somewhere that talked about, teachers, I don't remember the phrasing, but it was basically about teachers aren't teaching for the money they're teaching for what the output that students will have. And sure, do I believe that teaching is a vocation for me? Yes.

But am I a professional who deserves to be paid for my time? Also, yes. And I really wish that instead of saying teachers are superheroes or teachers are martyrs, that's the other one that comes up so much. Instead of perpetuating those narratives around educators, can we perpetuate the idea that teachers are professionals who know what they are doing, who have trained and who have skills that mean they should be both paid and treated like professionals. And I really think we need a whole switch in how this country sees teachers. I don't want to be a martyr. I am a professional.

Shamari: That's right. What would you say right now to educators who might be listening to us or other teachers?

Holly: I would say that there are a lot of really valid reasons to want to be a better teacher at all times. And to want to lean into that idea of perfectionism, that I need to spend four hours perfecting this lesson that's going to take 50 minutes tomorrow. There are lots of reasons that you might be inclined to do that. And yet, if we are not people with lives outside of our profession, we are not going to be as good as we can be in this work. And we're not going to be the people that our students need to see as role models. And I would also say that I think those myths of teachers being superheroes and teachers being martyrs perpetuate a sense of guilt and shame in teachers who aren't always doing the absolute most. And guilt and shame are never the right motivators for anything.

Shamari: And so I have two final questions, Holly. And so, this podcast is called Water for Teachers. This is our first episode, which I'm super excited about. And water for me has always symbolized restoration and the healing and relaxation, memory reflection, nourishment. And so, I want to end with an abstract question and then a question that it's not so abstract. So here's the appetite question. And I trust that you'll do with it, what you will. What is your water?

Holly: Well, I'm going to give an abstract answer to an abstract question. My water is love. And I feel very grounded in my life, both in the love I've come to hold for myself and the value I hold in myself. And also, the love of really solid, stable friendships, and family relationships, and my romantic relationship with my partner. Those are things that are grounding for me and love is the purpose that I go forward in. So, I guess, just moving in love is what nourishes me.

Shamari: Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. Wow. I love love. So, I don't know if you knew that, but I am feeling so many things right now and I always say to myself when I wake up, "Love now, love always. Love now, love always. Love now, love always." I believe it's quite powerful. Final question. What connections do you see between a vulnerability and the art of teaching?

Holly: I guess what I see the most in the connection between vulnerability and the art of teaching is that in order to be the most powerful teacher possible, you have to be vulnerable. Because we have both talked about when we walked into the classroom, thinking we have the answers, that's when we failed the most. And yeah, you have to be vulnerable in order to make space for the idea that I don't know it all. And so, vulnerability is necessary and just a key component of listening to our students, of believing them and of knowing that they bring knowledge and wisdom into the space, the same way that we bring knowledge and wisdom into this space. And it requires vulnerability to give up control and a good teacher doesn't always have that control.

Shamari: And so, for those of you who are at home listening, I'd like to invite you to join this conversation. Take a moment and sit with that final question. What connections do you see between vulnerability and the work of teaching? And if you feel so moved, please share your responses with us.

I would like to engage with you in your humanity. You can share your responses with us using Twitter. There's a hashtag water for teachers, altogether, or you can tag us using our Twitter handle @water4teachers. That's water, the number four, teachers. Thank you, Holly, for sharing this space with us. Thank all of you for listening. Until next time, peace and love.

…

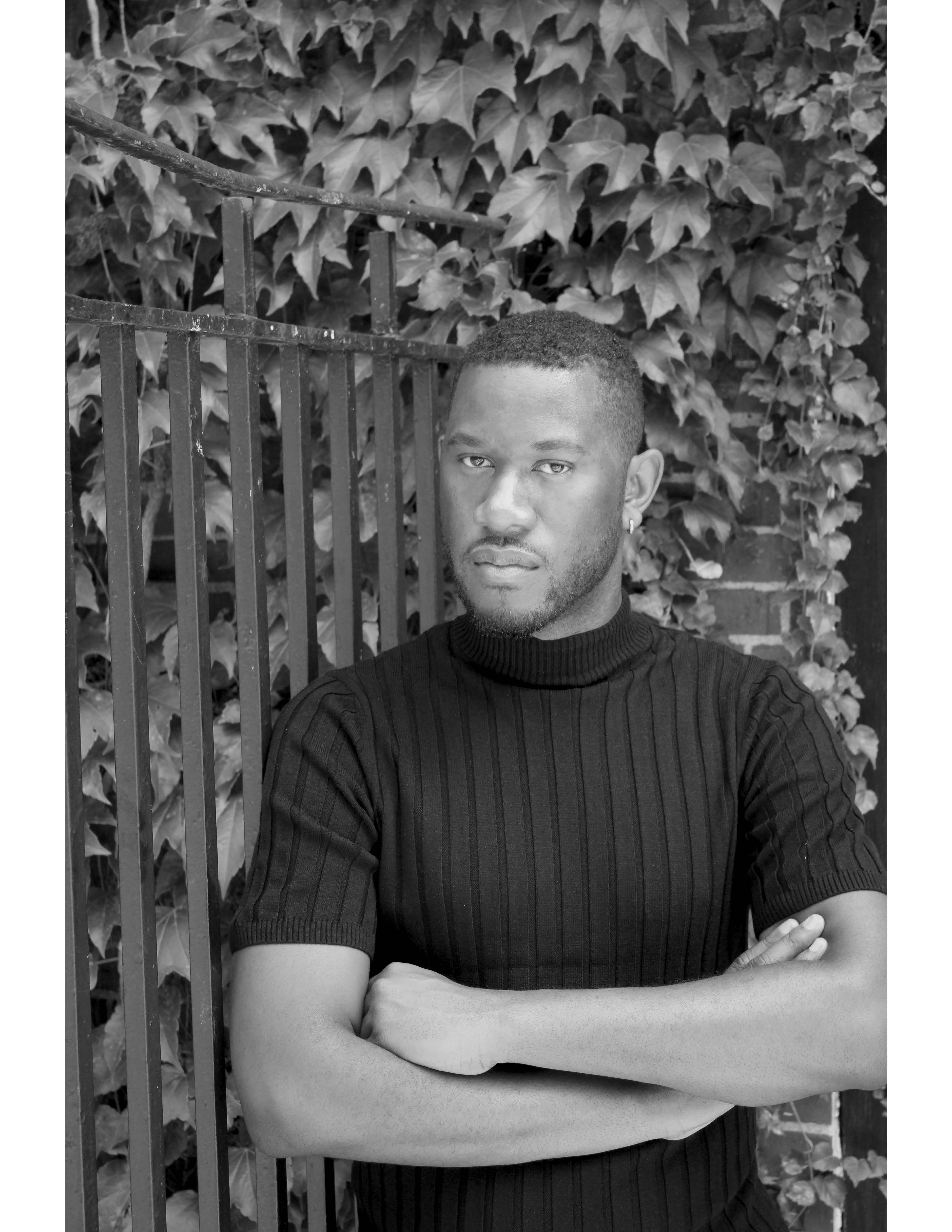

Shamari K. Reid I often refer to myself as an ordinary Black Gay cisgender man from Oklahoma with extraordinary dreams. Currently, that dream involves completing my doctoral work at Teachers College, Columbia University in the department of Curriculum & Teaching where I focus on urban education and teacher education. Before starting my doctoral program, I completed a B.A. in Spanish Education at Oklahoma City University and an M.A in Spanish and TESOL at New York University. I've taught Spanish and ESL at the elementary, secondary, and post secondary levels in Oklahoma, New York, Uruguay, and Spain. In addition to my doctoral work, I have spent the last few years as an instructor at Hunter College- CUNY offering courses on the teaching of reading, urban education, and language, literacy, and culture. I have also been engaged in work as a consultant for the New York City Department of Education’s initiative to combat the discrimination students of color face. My research interests include Black youth agency, advocacy, and activism and transformative teacher education. I am currently in the process of completing my dissertation on the agency of Black LGBTQ+ youth in NYC. Oh, and I have small addiction to chocolate chip cookies.

Shamari K. Reid I often refer to myself as an ordinary Black Gay cisgender man from Oklahoma with extraordinary dreams. Currently, that dream involves completing my doctoral work at Teachers College, Columbia University in the department of Curriculum & Teaching where I focus on urban education and teacher education. Before starting my doctoral program, I completed a B.A. in Spanish Education at Oklahoma City University and an M.A in Spanish and TESOL at New York University. I've taught Spanish and ESL at the elementary, secondary, and post secondary levels in Oklahoma, New York, Uruguay, and Spain. In addition to my doctoral work, I have spent the last few years as an instructor at Hunter College- CUNY offering courses on the teaching of reading, urban education, and language, literacy, and culture. I have also been engaged in work as a consultant for the New York City Department of Education’s initiative to combat the discrimination students of color face. My research interests include Black youth agency, advocacy, and activism and transformative teacher education. I am currently in the process of completing my dissertation on the agency of Black LGBTQ+ youth in NYC. Oh, and I have small addiction to chocolate chip cookies.

Holly Marie Jordan has been a public school teacher for fifteen years, all of them at Hillside High School in Durham, NC, where she teaches International Baccalaureate English, advises the Hillside Gender and Sexuality Alliance, and mentors preservice and beginning teachers through the Duke University Master of Arts in Teaching program and the Duke Teach House fellowship.

Holly Marie Jordan has been a public school teacher for fifteen years, all of them at Hillside High School in Durham, NC, where she teaches International Baccalaureate English, advises the Hillside Gender and Sexuality Alliance, and mentors preservice and beginning teachers through the Duke University Master of Arts in Teaching program and the Duke Teach House fellowship.

As a white, cisgender, able-bodied, middle class woman, Holly came of age in Illinois and Wisconsin with little understanding of systemic racism or of her own privilege. Her experience teaching the phenomenal students of Hillside High, Durham’s historically Black high school, changed the trajectory of her life. Now, she is an active learner and teacher of racial and social justice both inside and outside of the classroom. Holly is a former chair of the Safe Schools North Carolina Board of Directors and frequently leads professional development about LGBTQ+ equity and inclusion, anti-racist teaching, and teacher well-being.

Holly lives in Durham with her partner Dolores, their animal friends, and an ever-increasing number of houseplants.

Bonus! Check out the preview episode of Water for Teachers!

Steph: Hey, everyone. This is Steph from Heinemann, and I'm so excited to share with you all a teaser episode of a brand new miniseries called Water For Teachers, coming out on the Heinemann Network soon. Today, I'm going to be talking with Shamari Reid, who is the host and creator of Water For Teachers. And we hope that you stay on after our conversation for a short preview of the first episode.

Shamari is a human who teaches. He began his career in education as an ELA and Spanish teacher, and now he works with pre-service teachers as a teacher educator. And he also loves chocolate chip cookies, and is learning to play the guitar. So Shamari, welcome. It is so great to see your face again.

Shamari: Hi It's really weird to be on this side of it, right?

Steph: Yeah, yep.

Shamari: I'm so used to being on that side. And it's like, "Oh, now they're going to ask me." But I'm excited. Thanks for having me.

Steph: Yeah. Thank you for joining us. So for listeners who don't already know you, in as many words as you're comfortable sharing, could you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you came up with the idea for the Water For Teachers podcast?

Shamari: Of course. You know that... So I'm not really a shy person and I have no problem talking about myself, but that question, right? "Tell me a bit about yourself." It reminds me to times I've been on dates, that's where I think I hear it the most. And the date is like, "So tell me about yourself." You're like, "What?" And I just get speechless.

So what I'll say now is I'm a human, I am a human who is beautiful and complex, imperfect, flawed, and incredible. And just like Brené Brown says, who I love, "Though I'm imperfect and I'm flawed, I am human and worthy and deserving of the most beautiful things life has to offer." I think the idea of Water for Teacher really comes from that, from my knowing that I'm a human and that teachers are humans too.

And so I wanted to sort of position the podcast as an invitation for educators to come together, to have conversations, and to be human. Come together and breathe, especially in a world in which educators are sometimes treated like machines, who are supposed to just do and do and do. And in a world in which we are bombarded with messages about how we should do our jobs and all the things that we are doing wrong.

I just wanted us to have a place where we could explore our humanity together. Where we could pause, where we could hydrate and nourish ourselves, because like other humans, we need to be watered too.

Steph: I love that. And you alluded so perfectly to my next question, which is about this phrase that you use, I think in every episode, which is humans who teach. And it struck me every time you said it, because I grew up with a parent who's a teacher and I have so many memories of like early elementary school before break.

And there'd always be these conversations like, "Where do you think the teacher's going to go? Are they going to sleep here?" And I'd always be thinking like, "Yeah, like they go home." And that's obviously a silly thing I think a lot of kids think and we grow out of it. But as you just said, even as adults, we assume teachers to be teaching machines.

Shamari: Yeah!

Steph: So again, I know you just kind of alluded to this, but can you talk a little bit more about that phrase and what it means to you and why you use it?

Shamari: It's a reminder, I think to myself, but to others too, that we are humans first. And yes, we teach, but we're still human. We still have needs that must be met. We are also living through a time of collective crisis and we love and we cry and we hurt and we heal.

And so it's a reminder that all of us are humans. And I do mean all of us, those of us who teach, those of us who do other things, we are all humans. And as humans, we're all valuable and worthy of being here. And I know that because we are here. And so my using that phrase is just to say, you are human first. You are valuable. You are worthy of being here.

And I know that because you're here. And if you weren't supposed to be here or if you didn't matter, then you wouldn't be here. But yet look. Here we all are, here, as humans. And so it's just a reframing to really invite everyone, including educators, to think of ourselves as people who have needs, who've loved and who've lost and who have dreams. But just to get back to our collective humanity,

Steph: That's beautiful. And you have all these very human themes for each episode. What are the themes that listeners can look forward to hearing?

Shamari: Yeah. So, I'm really excited to also talk about how they came to be.

Steph: Yes!

Shamari: They were really organic. And so many of the guests who you will meet throughout the podcast, I didn't know any of them before. I mean, that was sort of a requirement that I told myself, I wanted to talk to other humans who teach, who I didn't know. I wanted to get to meet people on the air.

But to sort of plan some of the themes I had these initial conversations with everyone who was interested. And I'm so grateful to share that there were a lot of folks, a lot of humans who teach, who wanted to be a part of this. And so through talking to them, I noticed trends and patterns and things that were on their minds. And so I figured these were teachers and here's what's coming up for them organically. And so I think the podcast has to explore these things.

And so what came up was vulnerability, our imperfect humanity, our identities, intersectionality, our ability to love as humans and how we sent our love in the classroom, confronting our fears and doing what's best for students, joy. And so what you'll find throughout the episodes are these themes that I'm so grateful to the people, honestly, who are a guest on the show, but also who reached out to me to just talk about it before.

I owe all of them a huge thank you because the themes and ideas really did come from conversations I've had with all of them. And so I can't take credit. I just sort of sat back and let the world go. And I went with it. And these are the things that sort of were illuminated, if you will, to me, through having conversations with these wonderful people who teach.

Steph: And the very first episode of Water For Teachers is out on February 4th. It should be about a week from when this preview is released. What are you hoping that listeners will take away from the show?

Shamari: Wow. I hope they walk away, the humans who teach who listen, and any human who listens in, but I hope they walk away knowing that as someone I love, Toni Morrison, reminds us, that you are your best thing. I hope they walk away knowing that you are your best thing. Take care of your best thing. Spend time with your best thing. Nurture your best thing. Water your best thing, because you are worth it.

And I hope that this podcast and the first episode really are invitations for you to begin to explore your own humanity, your own best thing. And figuring out what your best thing needs, what things you want to hold onto, and what things you want to let go of, so that you can lead a life full of peace, love, and joy.

Steph: Beautiful. Shamari, thank you so much for joining us for this quick conversation today. For anyone listening, you can listen to Water For Teachers on the Heinemann podcast feed. So if you're not subscribed already, please go ahead and subscribe. You can also follow @Water4Teachers, that's with the number four, on Twitter. And please enjoy this preview of Water For Teachers.

…

Shamari: And there are just so many misconceptions about our work. And even in a way I feel that's dehumanizing, to expect us to be able to take a weekend and bounce back and have everything sort of transitioned to remote instruction. That is wild to me.

And as a human I'm just like, "No, I'm also affected. I'm also tired. I'm also losing people. And so I need time to mourn and grieve. And you want to give me two days to turn 15 years, mind you, 15 years of curriculum that you've built and adapt it for an online space?"

That is dehumanizing. And that is why I think, for me, this podcast is so important. It's like, "We are people. You can not treat us like this. You cannot treat us like robots. We need time too. We need care too."

And so I wanted to ask, as we think about misconceptions, as a human who teaches, what do you wish others knew about you and your work?

Holly: Well, what you just said brought to mind is this narrative around teachers that I think a lot of people think is flattering, which is that teachers are superheroes. The shirts that say, "I teach, what's your superpower?" Or I saw another sort of meme going around Facebook or somewhere that talked about, "Teachers..." I don't remember the phrasing, but it was basically about teachers aren't teaching for the money, they're teaching for the output that students will have.

And, sure. Do I believe that teaching is a vocation for me? Yes. But am I a professional who deserves to be paid for my time? Also, yes.

And I really wish that instead of saying, "Teachers are superheroes." Or, "Teachers are martyrs." That's the other one that comes up so much. Instead of sort of perpetuating those narratives around educators, can we perpetuate the idea that teachers are professionals? Who know what they are doing, who have trained, and who have skills that mean they should be both paid and treated like professionals.

And I really think we need a whole switch in how this country sees teachers. I don't want to be a martyr. I am a professional.

Shamari: That's right.