Written by Kara Pranikoff, author of Teaching Talk: A Practical Guide to Fostering Student Thinking and Conversation

Educators are granted the incredible gift of revision, a chance to reflect on and refine instruction year after year. Try again. Do over. Make better. At its core, education is a creative process, facilitated by a teacher and constructed by the student community. It’s a meeting of the minds.

In the fall we aim for instruction that will introduce the fundamental concepts we’ll nurture across the year. I’m dedicated to creating a classroom where student ideas and voices are the foundation of our daily discussions.

Our first work is to tune into the internal voice that comments, questions, and thinks alongside the words in a book. At every age, it’s these thoughts that bring books to life and construct meaning. “For the reader, the literary work is a particular and personal event: the electric current of his mind and personality lighting up the pattern of symbols on the printed page,” writes Louise Rosenblatt in her collection of essays Making Meaning with Text (2005, 63). I love this image, as if readers can suddenly be aware of the reading moments that cause their synapses to glow red with ideas. How can teachers harness this energy, hold on to student thinking and the moments in text that make brains light up?

One key is for teachers to stay quiet (yes, it’s more difficult than it might seem) so that students can see by our actions that we prioritize their ideas. Consider shifting your read aloud routine. When you pause to talk, ask your students to do the work. Open the class conversation with the simple question What are you thinking? and proceed by recording what is shared. No judgments or guidance, and verbatim as well as you can.

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

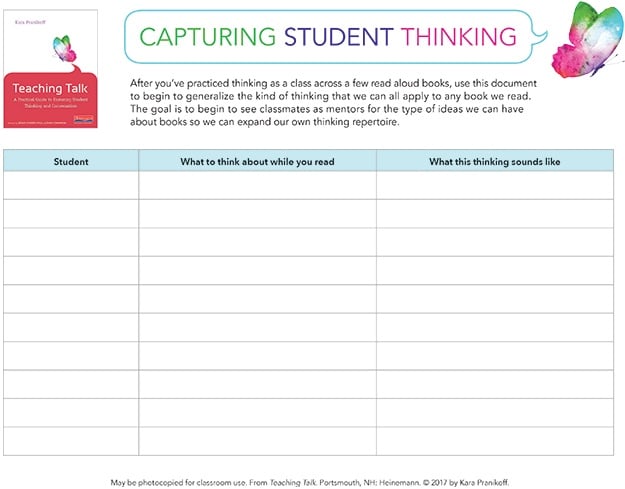

What to think about while you read

What this thinking sounds like

⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼⎼

After you’ve read a few books in this fashion your students will see that their ideas are what matter most. Soon you’ll have enough information to make some generalizations that will support independent thinking across the year. The examples below come from the work of Lauren and Arielle’s fifth-grade class after reading several picture books by William Steig.

| What to think about while you read |

What this thinking sounds like |

| How books make you feel |

Amos and Borris makes me feel a combination of happy and sad |

| Recognize yourself in a text. Compare yourself to the text |

Sometimes, I get grumpy like Spiny, and no one can cheer me up |

| Ask big questions |

Why would a writer write about something sad? |

Teaching Talk, pg. 96

Now is the time to curate a pile of books that make readers stop and think and react. Be sure to include a variety (realistic fiction, nonfiction, fantasy, poetry, even wordless books) and plan to share them across the first month of classes. Choose one to read each day and make space for your students to talk and think.

To get started, ask students to turn and talk with a partner each time you pause your reading. This ensures everyone has some beginning time to process their thoughts. Then, you can open the discussion up to the whole class by simply asking, What are you thinking?

You can also offer students a chance to keep track of their thinking through writing. As you read aloud they can record their ideas in whatever way is easiest -- scribble in a notebook, jot on a sticky note, or mark up a copy of text. Again, provide time for students to share with a partner before they get their thoughts out into the open with the whole class.

Remember, you’re not aiming for anything profound. That takes time and practice. Your goal right now is for students to know that this is the year that their ideas take center stage. Students never disappoint, so enjoy your listening.

Here’s a document to get you started.

♦ ♦ ♦

To learn more about Teaching Talk: A Practical Guide to Fostering Student Thinking and Conversation, and to download a sample chapter, visit Heinemann.com.

♦ ♦ ♦

Conversation seeker and careful listener, Kara Pranikoff is fortunate to spend her days learning with children and teachers. Currently a literacy coach, you can find Kara at PS 234, a progressive, inquiry-based school in NYC where she works alongside teachers to strengthen their reading and writing instruction. Kara has been a classroom teacher in NYC and at a Title 1 school in Buffalo, NY. She has taught small groups of students in reading intervention, co-led a series of workshops for instructional coaches in her district, and has been a literacy consultant for schools outside of the city. She speaks at national conferences about the ways teachers can foster productive, dynamic, and independent student discussions.

Conversation seeker and careful listener, Kara Pranikoff is fortunate to spend her days learning with children and teachers. Currently a literacy coach, you can find Kara at PS 234, a progressive, inquiry-based school in NYC where she works alongside teachers to strengthen their reading and writing instruction. Kara has been a classroom teacher in NYC and at a Title 1 school in Buffalo, NY. She has taught small groups of students in reading intervention, co-led a series of workshops for instructional coaches in her district, and has been a literacy consultant for schools outside of the city. She speaks at national conferences about the ways teachers can foster productive, dynamic, and independent student discussions.