In author Dan Feigelson's new book, Reading Projects Reimagined, Feigelson shows us how conference-based, individual reading projects help students learn to think for themselves. Feigelson raises an important question about the larger goal of reading instruction: while it’s our job as reading teachers to introduce students to new ideas and comprehension strategies, shouldn’t we also teach them to come up with their own ideas? In today’s blog, Feigelson uses a conversation with a 5th grader to bring home the importance of allowing kids to do reading work based on their own thinking.

In author Dan Feigelson's new book, Reading Projects Reimagined, Feigelson shows us how conference-based, individual reading projects help students learn to think for themselves. Feigelson raises an important question about the larger goal of reading instruction: while it’s our job as reading teachers to introduce students to new ideas and comprehension strategies, shouldn’t we also teach them to come up with their own ideas? In today’s blog, Feigelson uses a conversation with a 5th grader to bring home the importance of allowing kids to do reading work based on their own thinking.

Helping Kids Expand their Own Ideas

Written by Dan Feigelson

Fifth grader Bronwen, like many upper elementary and middle school students, couldn’t get enough of dystopian novels. After going through the entire Hunger Games series in a week and a half, she had moved on to Lois Lowry’s The Giver. When I sat down for a conference with her and asked what she was noticing about the genre, she thought for a minute. “Well, they aren’t the easiest kind of books,” she finally responded. “You sort of have to know how to read them.” Intrigued, I asked her to say more. “Well, there are certain kinds of parts where you really have to stop and pay attention. Like here in Chapter 2—Jonah’s parents are telling him about the Ceremony of Twelve, where he’s going to find out what his job will be when he grows up.”

I was genuinely curious. “You said there were certain kinds of parts. What kind of part is that one?”

“Well, it’s like when there’s a big ceremony it’s usually really important. And also, Jonah’s parents are explaining it to him. I’ve noticed that when a parent or some older person explains something to a younger person that’s usually a big deal.”

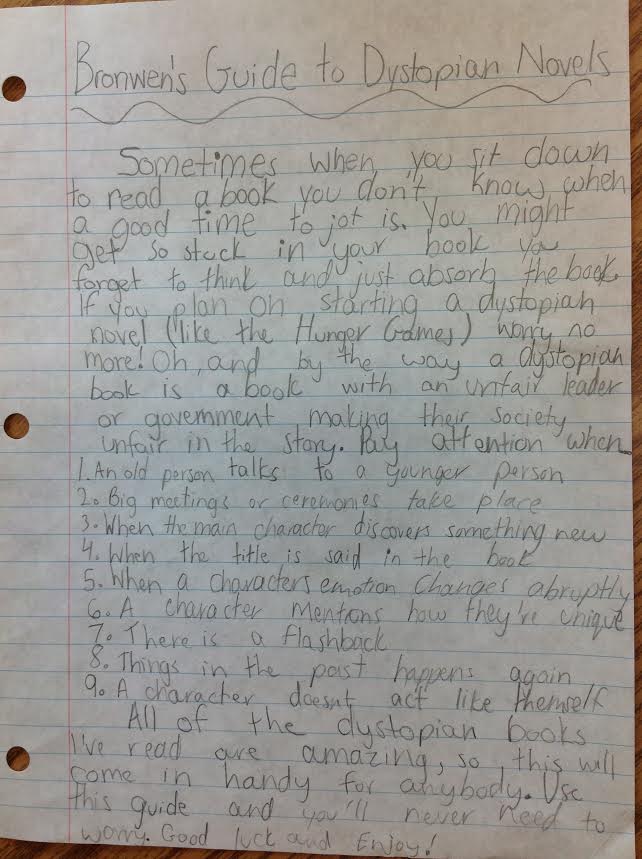

After a couple more minutes of conversation, I suggested that her reading work for the next several days could be to put together a guide to dystopian novels, teaching other readers where they should stop and pay attention. Here’s what she came up with:

My conversation with Bronwen didn’t come out of nowhere. Most people who become teachers do so, at least in part, because they are fascinated with the way kids think. At one time or another each of us has marveled at some idiosyncratic piece of wisdom coming from the mind of a child.

Sadly, once we enter the hectic life of the classroom the ideas of students tend to take a back seat to standards and units of study. Schools and districts are under enormous pressure to achieve and to test well. This means kids must be able to perform at a level comparable to other children of the same age. A teacher who cares about the success of her students has little time to concentrate on the quirky ideas of each individual kid—especially when it comes to core academic subjects like reading.

It’s not that paying attention to literacy standards is a bad idea; wise curriculum is critical for a good reading class. Indeed, we wouldn’t be doing our job as educators if our fourth graders finished the year without knowing the stuff fourth graders are supposed to know. But the truth is most students are raised on a steady diet of clever comprehension questions formulated by teachers or commercial programs. The result is that kids—even those who do well on state tests—often have a hard time knowing how to approach a complex text when there is no one there telling them what to think about.

Over the last several years I’ve had the good fortune to explore this issue with many courageous teachers. We’ve realized that at least some of our time in reading class should be spent teaching kids to recognize, name, and extend their own ideas about what they read.

To do this well means getting back to that original passion all teachers share. We need to allow ourselves the time and space to be fascinated with what our students think. This means that when we ask them to comment on a story or an informational text, we listen for the most interesting part of what they say and ask them to say more about that rather than quickly going on to the next child—or jumping in with our own agenda. And lo and behold, when kids do reading work based on their own thinking they are more engaged, more independent, and willing to take on new challenges. The classroom takes on a very different buzz. The rigor goes up, not down—and it carries over into whole-class curriculum work as well.

In Reading Projects Reimagined I’ve laid out a series of steps for teachers to use in individual reading conferences so their students can engage in rigorous work based on their own thinking. My hope is that these sorts of conferences will help create joyful, independent student readers who are just as good at coming up with their own ideas about books as they are at answering questions on tests.

Click here to download a sample chapter and for more information on Reading Projects Reimagined.