Though I wish it could be, planning one’s own growth is not as simple as choosing a smart technique and trying it. There are times when you will have to be strategic about how you move forward. This work is equal parts mind-set, communication, and classroom execution. The steps in this process do not flow in a linear order, but when planning for how I want to grow to be better for children, I tend to start with mind-set. For me, the hardest work is always on my own attitude about the work at hand, so I start there.

Engage in Imaginative Mind-Set Work

There are so many times at school when we believe that nothing will change. Though some may see it as such, this is not being negative. Many of our beliefs that things will never change are built upon experience. You know your building; you know your colleagues; you know how things tend to go. It is important here to acknowledge the traditions, limitations, and patterns that you know to be true, but it is more important to begin to imagine the new realities that can be true. When we want to be self-determining in terms of our professional growth, the first thing that we can do is believe that things can be different. We certainly cannot expect to change an entire school or even a classroom yet, but we can change how we respond to the things that happen in those places. This response and the kind of imaginative work that we can choose to do after it is at the center of any freedom struggle. Specifically, imagination will be central to the work of being free to grow in the ways that can most powerfully serve our students. Whenever I find myself complaining or gossiping about a thing, I know that it’s time to do some growing. I understand that the stories that I tell at the teacher happy hour—the “Can you believe that?!” ones—are coping strategies, not change mechanisms. These stories, and the valid complaints that they personify, allow me to laugh, cry, or shrug my way through the impossible things that happen daily. They allow me to cope. They do not make the impossible situation possible. But they can. A lot of the stories that could potentially lead to change get left at the bar or in the teachers’ lounge or in the tear-stained box of tissues in my best friend’s classroom.

Each of the stories that we tell about our work, no matter how we embellish or downplay it, communicates some truth about the realities that we live. Taken collectively, those stories point to the persisting is-sues and to the school power structures that can plague us. And they shed some light on how we can work on ourselves so that we may better survive these things and develop the power to eventually change them altogether. As I imagine change in the context of my own work, I sometimes have to fight the urge to say, “That’s impossible,” or “They won’t let me do that.” You’ll have to do the same. Remember that to many of our heroes, freedom from bondage, full suffrage, and complete citizenship were impossible dreams too. When impossibility keeps surfacing, one way to push past it is by say-ng, “What if?” What if I could change the way that the kids entered the room? What if I could allow for more choice? What if I could engage kids differently? What if I had more time to take care of myself? Imagine what that would look and feel like, and assume, for now, that it is possible. Figure 6.2 shows one way that your strategic imagination can work.

Once I have started this imaginative mind-set work by considering my stories, I continue it by considering the actual work. I get to build the thing of my dreams. Here’s the thing about this, though: the thing in our dreams—that thing that we want for our classroom or our students or our community or ourselves—exists in our mind in a state of imagined perfection. As educators, sometimes we fail to act on our dreams because we fear that we cannot attain the perfection that we imagine. In truth, we won’t find this perfection right away. Dream work is messy, but when faced with the choice between the sometimes broken reality of what currently exists and the messy reality of progress, it is better to live in the mess.

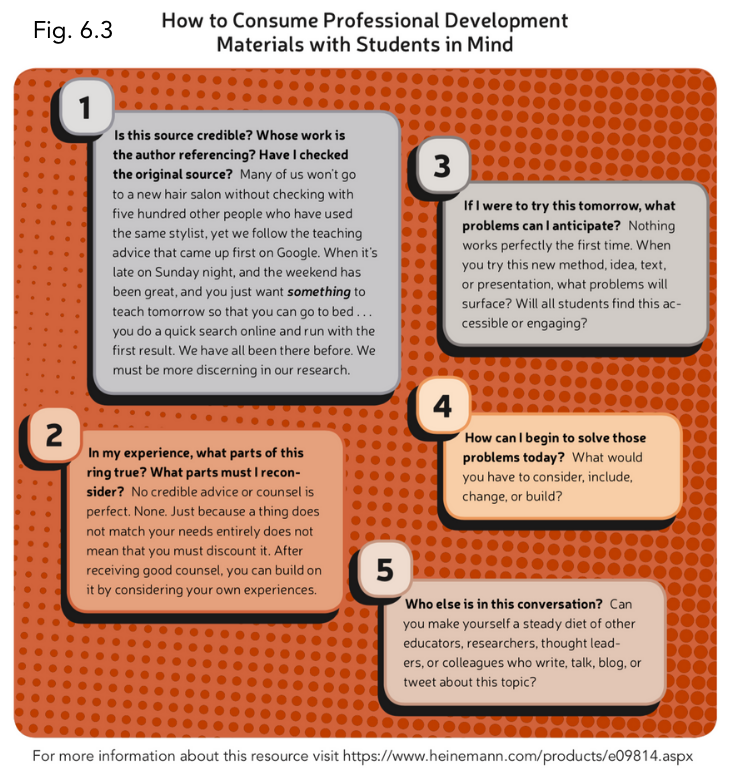

If we choose to act, things can be different. They won’t be radically different right away, but they can be incrementally better. The longer I stay in it, the more I realize that our work is more evolutionary than it is revolutionary. I always have to remind myself here that I am not the first educator to ever struggle. I’m not the first one to dream of better, and I’m not the first one to try to imagine tomorrows that are slightly better than our todays. As such, when I’m thinking about things that I can do or approaches that I can take to solve my problems or work through my challenges, I can lean on the experience of others as presented in books, articles, conversations, or virtual interactions. I can learn from their mistakes and stand on a foundation of their successes. When engaging in this kind of learning, it is important to do so authentically by remembering that we are doing this kind of thinking to free ourselves. We are not running from one orthodoxy to the next. This is not the work of questioning the methods of the leaders at school only to embrace the methods of random people on the Internet. This is the work of questioning everything and building paths for our-selves and our students based on our own study, consideration, planning, and trial and error, not on someone else’s promises of shortcuts and miracles. When I consume professional materials, I do so with my students in mind always. Unless the person whose advice I’m following personally knows my students, I ask the questions in Figure 6.3. Once I learn how to listen to advice, this impacts how I attend professional development, how I read professional texts, and how I surf the Internet. When you read, listen, think, and question powerfully, you’ll find that you are all the expert that you’ll ever need.

To learn more about We Got This visit Heinemann.com.

Cornelius Minor is a frequent keynote speaker for and Lead Staff Developer at the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. In that capacity, he works with teachers, school leaders, and leaders of community-based organizations to support deep and wide literacy reform in cities (and sometimes villages) across the globe. Whether working with teachers and young people in Singapore, Seattle, or New York City, Cornelius always uses his love for technology, hip-hop, and social media to recruit students’ engagement in reading and writing and teachers’ engagement in communities of practice. As a staff developer, Cornelius draws not only on his years teaching middle school in the Bronx and Brooklyn, but also on time spent skateboarding, shooting hoops, and working with young people.