Imagine a lesson that is accessible to all levels of learners. Students are actively engaged and believe their voices matter. Imagine a lesson where students have easy-to-use structures in place that support independence and thinking dispositions such as curiosity, open-mindedness, reflection, critical thinking, creativity, and innovation. As students collaborate, they realize learning is not just an individual process driven by the teacher but a social endeavor where understanding grows from a community of students making their thinking visible to one another. Last, imagine a lesson where you have time to observe students closely, reflect on their thinking and learning, and create curriculum that truly grows from their needs and interests.

For some time, my imagination for teaching and learning like this felt diminished. As I tried to balance the overwhelming parts of the job—new standards, materials, online testing, changing technology, meetings, growing administrative details, and minimal collaboration time—I found it harder and harder to stay focused on the deeper goals and purpose of my work. I lost a sense of what meaningful work was for me as well as my own understanding—not the district’s—of how to build lifelong learners who were prepared for the challenges of the 21st century.

As most teachers, I am also deeply concerned about student engagement. I am often aware of students’ passivity and lack of personal involvement in their learning, almost like they are waiting for learning to be handed down or are dependent on a select few students to do the work. I am sensitive and highly attuned to my students’ facial expressions and energy, and I often feel my rising anxiety and sadness toward those I may not be reaching.

This unease and desire to improve my practice propelled me to attend summer institutes and online classes at Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero, where I learned about the Visible Thinking framework—a framework that is transforming my teaching.

Visible Thinking is “a broad and flexible framework for enriching classroom learning in all content areas and fostering student development at the same time. One of its key goals is a shift in classroom culture toward a community of enthusiastically engaged thinkers and learners. Teachers are invited to use with their students a number of ‘thinking routines’—simple protocols for exploring ideas—around whatever topics are important.”

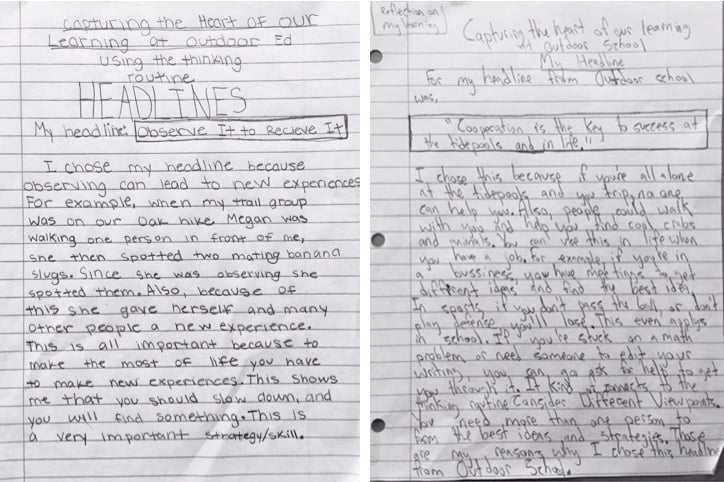

For example, to help synthesize their ideas or capture the heart of learning after a unit of study, reading a single text, or a class activity, my students frequently use a thinking routine called Headlines. A Headline is a sentence or phrase that shows what a student thinks is at the core of his or her learning, requiring reflection on what is important to remember about a topic or an issue. After drafting, students share their Headlines and their reasoning behind them.

To give you a specific example of Headlines in action, in the beginning of the year our class went for a week of outdoor school. When we returned, students wrote reflections about their learning. After generating ideas together in small groups, they wrote their own Headlines about what was most significant for them. Here are a few of the reflections alongside the Headlines they suggested:

These Headlines were a wonderful window into getting to know my students in the beginning of the year. Throughout the year, we have used Headlines to show the connections between ideas in our study of the early American colonies, to reveal quick snapshots of student thinking about themes in Home of the Brave (a story about a Sudanese refugee child coming to America), and to uncover what the main character comes to realize about himself in A Week in the Woods.

The Headlines routine helps students remember what is front and center in their learning and helps them make connections to future learning. Through discussions and writing, it makes their ideas visible to one another and helps them see multiple perspectives on a topic. Students who are quiet or who fear expressing their ideas in large class discussions engage more easily in the small group activity. As students share ideas, I am able to get a quick snapshot of student thinking and learning, which is informative and often surprising.

Other thinking routines we use in the classroom are organized around other specific types of thinking, such as looking closely, wondering, making connections, reasoning, building explanations, considering different viewpoints, and uncovering complexity. The easy-to-use frameworks have opened my eyes to how routinely used metacognitive tools can support engagement, independence, and a more dynamic learning environment for all learners.

Project Zero’s Visible Thinking framework and Ron Ritchhart’s books Making Thinking Visible and Creating Cultures of Thinking have motivated me to begin a journey of deep inquiry, observation, and reflection. They have led me to my Heinemann Fellows research question: In what ways does teaching students to be metacognitive through visible thinking support engagement and independence in the classroom?

As I delve into this new body of research that feels authentic and meaningful, I find I am imagining a new story about what good teaching might look like. In my upcoming blogs I will be writing more about my research and experience in the classroom using the Visible Thinking framework.

Hollis’ pedagogy is steeped in an emphasis on interdisciplinary learning, global citizenship, and visible thinking. “There is a social and ethical component to being a good teacher. Students need to learn how to be good individuals, citizens, and workers. They need to reflect and engage thoughtfully in conversations about social issues and how to take action, even if it is with simple acts of kindness.” Hollis is a 5th Grade Teacher at Montair Elementary School.

Hollis’ pedagogy is steeped in an emphasis on interdisciplinary learning, global citizenship, and visible thinking. “There is a social and ethical component to being a good teacher. Students need to learn how to be good individuals, citizens, and workers. They need to reflect and engage thoughtfully in conversations about social issues and how to take action, even if it is with simple acts of kindness.” Hollis is a 5th Grade Teacher at Montair Elementary School.