This is the second part of the "Social-Emotional Support for Adolescent Multilingual Learners" blog series, adapted from Andrea Honigsfeld's forthcoming Growing Language and Literacy, Grades 6-12.

***

Developing level adolescent learners’ well-being and academic engagement depend on a number of factors, of which you must already be mindful (no pun intended). Researchers have documented what you and I have witnessed when working with adolescents: there seems to be a gradual but predictable decline in engagement from the end of elementary school through about tenth grade. A team of researchers at OECD (2018) identified some important indicators specifically focusing on immigrant youth that we need to carefully consider and proactively address:

- students’ sense of belonging at school;

- their satisfaction with life in general;

- their level of school-related anxiety; and

- their motivation to achieve.

When students have high levels of motivation, when they have a sense of belonging, and when they understand how much adults care about them, they find a way to show it.

Have you ever seen any of your adolescent MLs becoming disengaged from the learning process temporarily or for a longer period of time? Have you tried to understand possible causes and search for viable responses? By using the following set of questions and selecting from the tips below each, you can get closer to understanding what might be going on and plan strategically to address these issues.

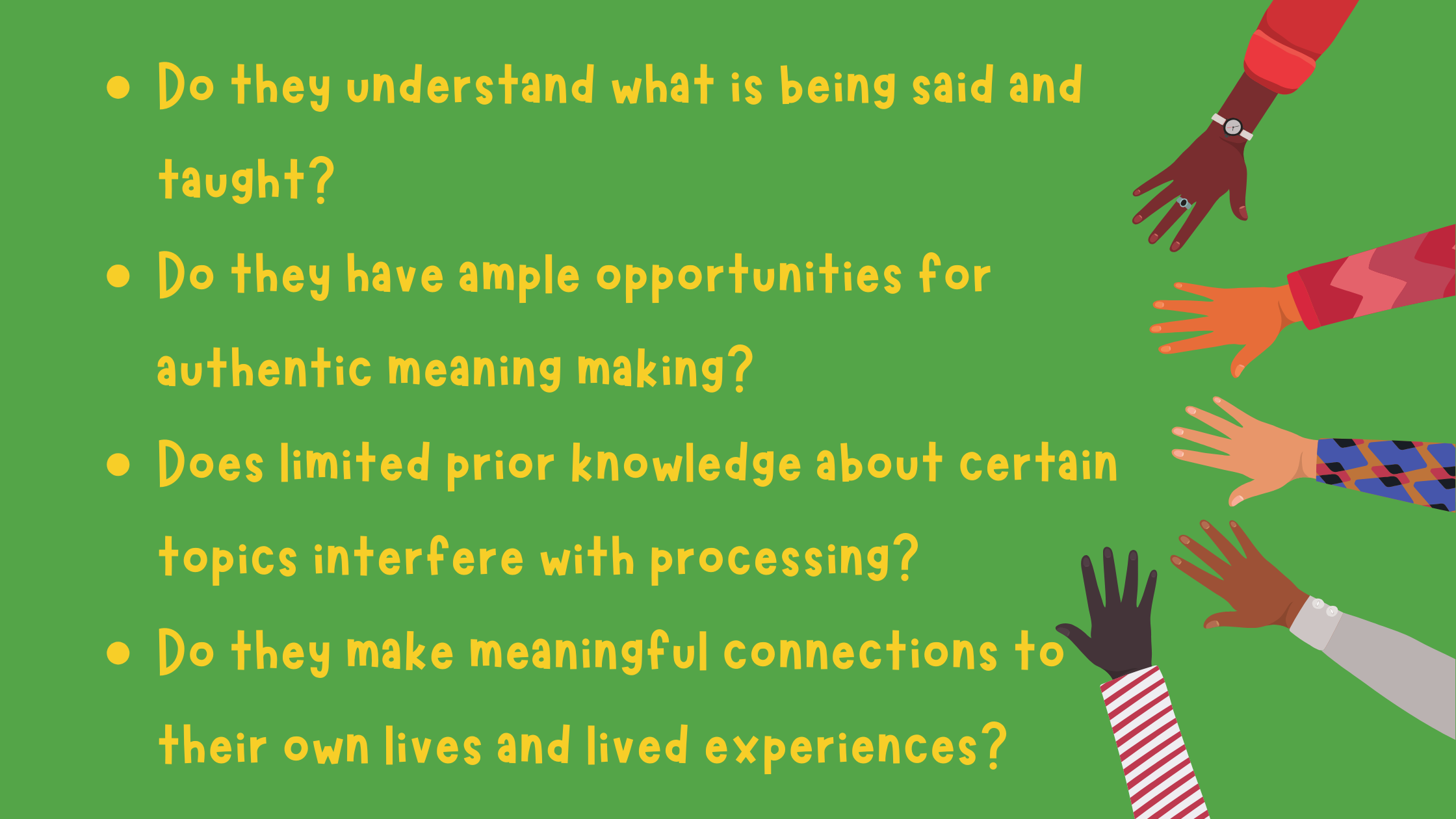

Do they understand what is being said and taught?

Do they understand what is being said and taught?

- Implement multimodal, multilingual, multilevel scaffolding.

- Check for understanding frequently.

- Encourage peer-to peer learning (students might just learn more from each other than from you).

- Use various models of lesson delivery and infuse technology tools to enhance comprehension.

- Teach about and encourage self-advocacy when students need help.

Do they have ample opportunities for authentic meaning making?

- Give students choices in their in-class activities and out-of-class assignments.

- Illustrate the usefulness and practical utility of what you are teaching.

- Encourage mistakes and help students to accept them as part of the natural process of learning anything.

Does limited prior knowledge about certain topics interfere with processing?

- Begin each unit with an irresistible hook.

- Continue your unit of study with a shared exploration of what everyone needs to know.

- Personalize aspects of the unit to better align to students’ interests.

- Flip your class by pre-teaching and front-loading essential background information.

Do they make meaningful connections to their own lives and lived experiences?

- Learn about your students so you can help make those connections for them and with them.

- Learn about your students’ countries of origin and cultural heritages.

- Learn a few phrases and sentences in your students’ primary languages (let them be the teachers and you the striving learner, trying hard to remember words and pronounce sounds correctly).

- Integrate your students’ out-of-school lives and literacies (including digital and nontraditional kinds of knowing) into the curriculum.

How would you determine your role in all this? How can you embrace a powerful stance as an educator of adolescent MLs? Borrowing from Lisa Delpit’s (2013) seminal work, let’s all collectively agree to be warm demanders, who “expect a great deal of their students, convince them of their own brilliance, and help them to reach their potential in a disciplined and structured environment” (77). The challenge—and amazing opportunity—you might be facing with this student group is to create a learning environment in which your students become and remain highly motivated and engaged to learn, an environment where they know and celebrate their own brilliance rather than get weighed down by perceived deficiencies. Can we collectively commit to that?

It is up to us to create vibrant learning spaces for adolescent MLs filled with peer interactions; project-based, hands-on, and kinesthetic learning; integration of visual tools and technology; recognition of what they already know; and so on. As Morrison and colleagues (2020) remind us, “non-threatening, nurturing environments fulfilling students’ cognitive, linguistic, and socioemotional needs contribute to higher academic achievement and motivation to learn science among bilingual students” (257).

***

Listen to Andrea in conversation with Pam Schwallier on the Heinemann Podcast.

Growing Language and Literacy: Strategies for Secondary Multilingual Learners, Grades 6-12 released on April 16th, 2024.

Dr. Andrea Honigsfeld is TESOL professor at Molloy University , Rockville Centre, NY. Before entering the field of teacher education, she was an English as a Foreign Language teacher in Hungary (grades 5-8 and adult), an English as a Second Language teacher in New York City (grades K-3 and adult), and taught Hungarian at New York University. A Fulbright Scholar and sought after national presenter, Andrea is the coauthor or coeditor of 27 books on education and numerous chapters and research articles related to the needs of diverse learners. Andrea is coauthor of the Core Instructional Routines books with Judy Dodge. Visit Andrea at www.andreahonigsfeld.com.