Historically, schools often viewed multilingual learners from a position of what they did not have: English proficiency or proficient performance on English assessments. I have heard teachers say things like, “They don’t have background knowledge.” I always reply that multilingual students have more background knowledge and experiences than we could ever imagine.

All of our students come with many cultural and linguistic resources, and it is our job to build on those “funds of knowledge” (Moll et al. 1992) and simultaneously support their ability to communicate those resources in English when their teacher and peers do not speak their home language. I view and frame all second language learning stages and processes as assets. Multilingual learners bring so many assets from their home language and experiences, and they are also learning English and academic content in English in school. That is impressive! All assets-based instruction begins with identification of what multilingual learners know, and the goals of all instruction are situated in what students can and will be able to do.

One important aspect of identifying students’ background knowledge, experiences, and prior learning is acknowledging that their current understandings will and should evolve and change over time with new learning. Research has documented that building on students’ background knowledge and experiences is an effective scaffold to introduce additional material and content that will deepen and extend their knowledge (Goldenberg 2013).

Five Instructional Strategies

The following instructional strategies draw on research findings to provide multiple approaches to identifying and building on students’ background knowledge and prior experiences to connect to new learning.

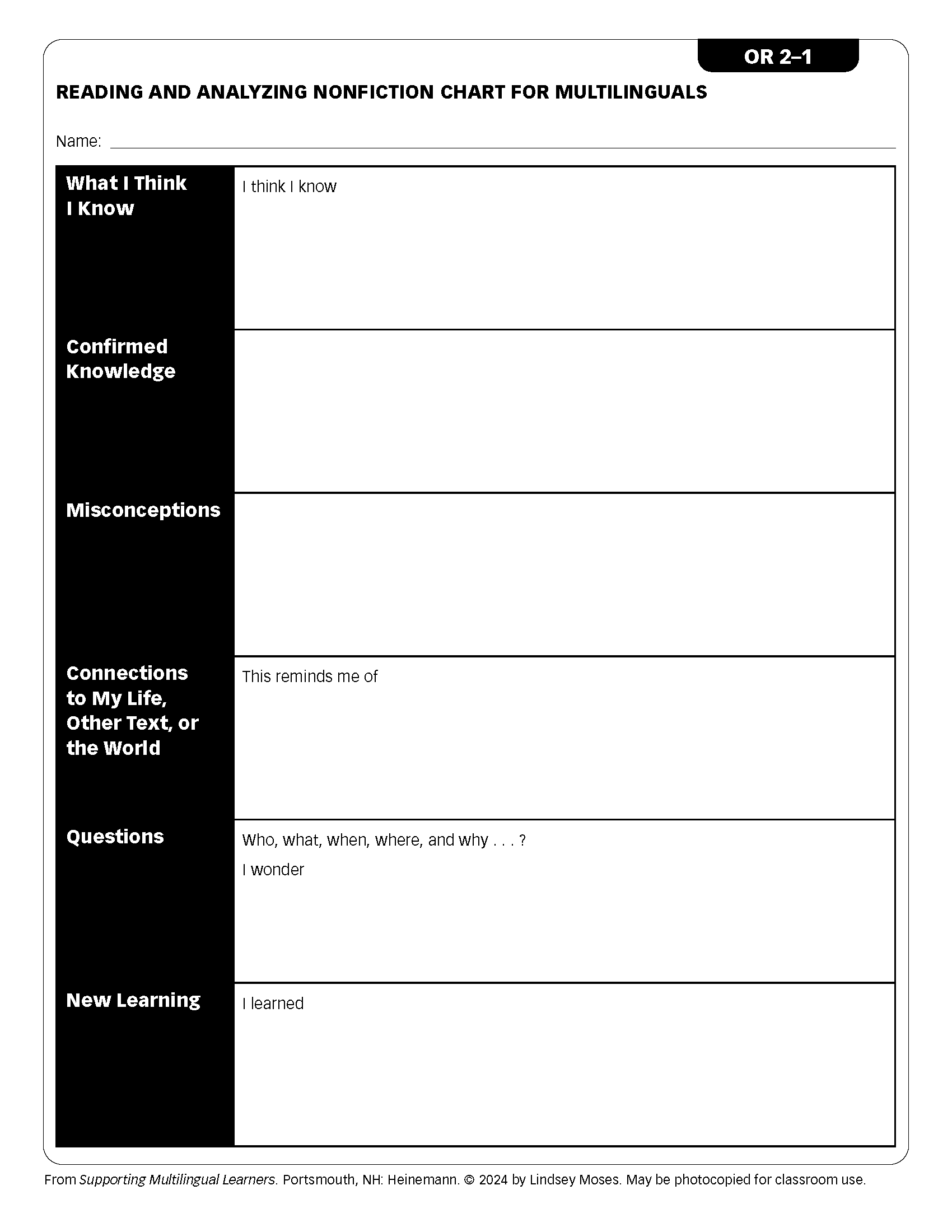

STRATEGY 1: RAN Chart with Multilingual Adaptations

The reading and analyzing nonfiction (RAN) chart (Stead 2006) remedies some of the limiting challenges of the KWL (know/want to/learned) chart by including five columns. The above version incorporates activating prior knowledge before reading, confirming and reevaluating that prior knowledge while reading, noting new information learned, and asking questions.

For multilingual students, this decreases the anxiety of being right and having to know something for certain and celebrates moving information from the “What I Think I Know” column to the “Misconceptions” column. You can use this instructional strategy with the whole class, small groups, or individuals.

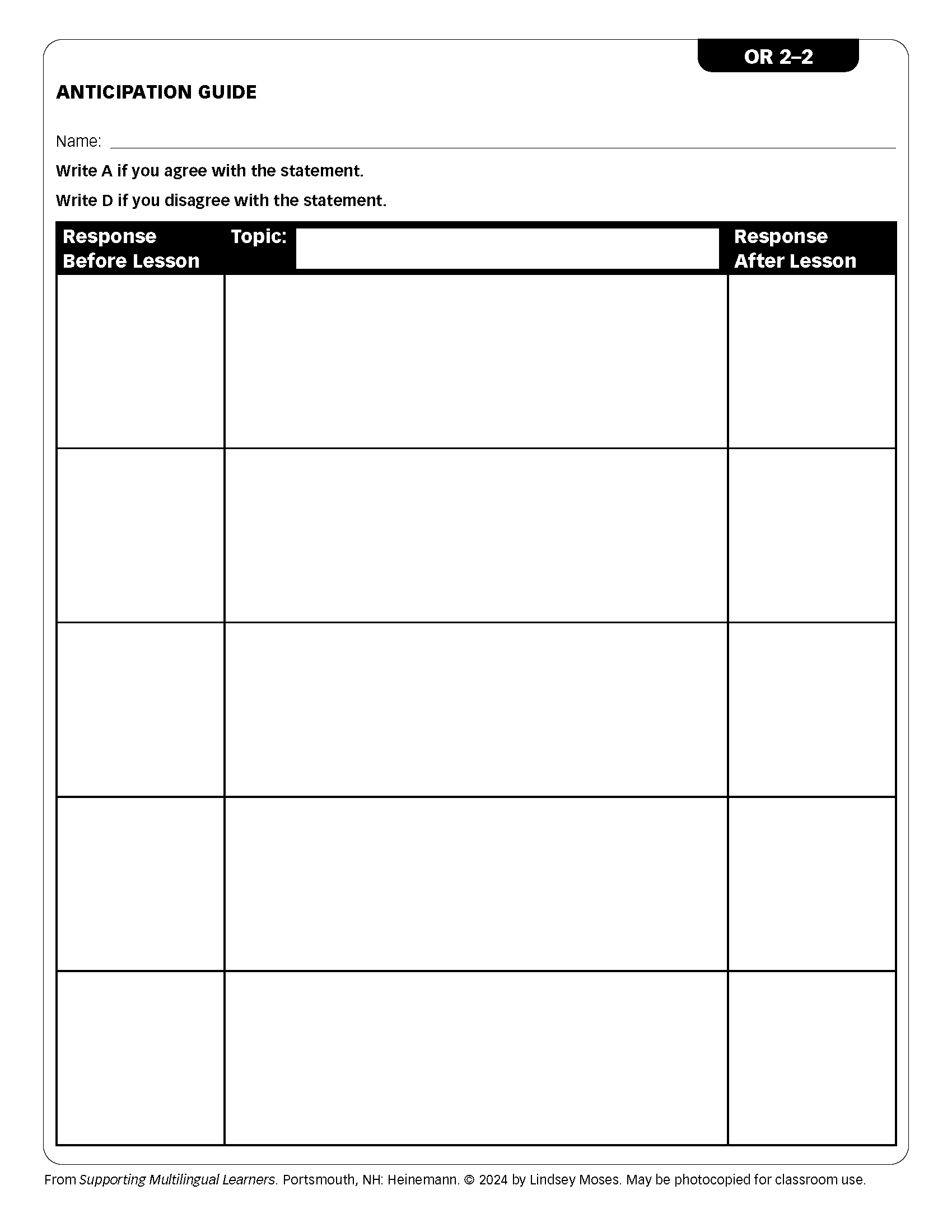

STRATEGY 2: Anticipation Guides

Anticipation guides include a series of statements related to the topic that students are going to read about or study. The anticipation guide is typically structured to require students to agree or disagree with the statements. Teachers ask students to complete the anticipation guide both before and after reading. The anticipation guide was originally developed by Herber (1978) with a purpose of increasing students’ comprehension of a text by actively involving them in making predictions with secondary students, but more recently it has been adapted to support learners of all ages.

Anticipation guides can take on various forms. The first is primarily informational, where the anticipation guide includes statements outside of common knowledge on the topic of study. Students respond to these statements, providing an initial assessment about their knowledge prior to the reading or unit. Then, students revisit the same questions after reading or the unit concludes to assess their learning. Depending on the language proficiency needs of your students, possible modifications include simplified language, translated anticipation guides, and modified or alternative text.

STRATEGY 3: Multimedia Preview and Preparation

Multimodal presentations of essential information can help students connect to their previous knowledge while simultaneously acquiring foundational concepts needed for the upcoming learning experiences.

The multimedia preview and preparation can take on many forms, such as a related video, slideshow, photograph, newscast, interview, or music. These should include engaging and interesting multimodal content related to the key ideas and concepts that will be part of the upcoming learning. Subtitles or information in students’ home language can be helpful for supporting multilingual students, and I also always add an opportunity for discussion around their noticings and reactions to the content.

STRATEGY 4: Making Connections

Proficient readers make connections while they read that help them better understand the text. These might include connections to their own lives or experiences, to other texts they have read, and to events or happenings around the world. While many readers intuitively make connections while they are reading, many students need explicit instruction about how to make connections before, during, and after reading. The classic comprehension strategy of making connections (text-to-text, text-to-self, and text-to-world) became popular and was used in many literacy classrooms after the release of Strategies That Work (Harvey and Goudvis 2000). Teachers modeled the strategies by reading a text and documenting their connections on sticky notes or in a reading notebook. Then they prompted the students to document their connections while reading and then share them with a partner or small group.

This comprehension strategy can be beneficial for all learners, but it is particularly helpful for students learning an additional language. It provides time and opportunities to document how students are connecting what they are reading to their prior knowledge and experiences. However, I have also seen some confusion and challenges with teaching this strategy when working with multilingual students.

For example, after a teacher and I taught this strategy to a group of second graders, the students thought they needed to use a sticky and write down a connection for anything that was familiar. We had a lot of responses like “There is a tree in the book. There is a tree outside,” or “They live in a house, and I live in a house.” As a way to encourage students to move beyond superficial use of identification and connection, we created an anchor chart with visuals to talk about the purpose of the strategy, modeled how to make a connection with language frames, and encouraged deeper connections.

STRATEGY 5: Getting to Know Your Students Through Asset Mapping

While this strategy might seem obvious, getting to know more about your students throughout the year can result in stronger relationships and opportunities for building on students’ interests and knowledge outside of school. Our relationships and our knowledge about our students should remain a focus and get deeper over time.

There are many ways to do this, including asking students to write personal narratives or autobiographies, participate in a passion project (where you dedicate research, reading, and writing time in school for studying a topic of interest), or create a multimedia presentation of the assets and resources in their local community. Another option could be creating surveys or reflection opportunities for students to discuss their skills and community practices outside of school. The possibilities for classroom applications and connections are endless when we know more about the strengths and resources in the communities in which we teach. The strategy of asset mapping is a learning experience for teachers and students.

.jpg)

Lindsey Moses recently visited the Heinemann podcast to discuss community asset mapping. Listen here.