Among the many attributes you might assign to teacher Michelle Logan, ‘dragon whisperer’ is not one that might first come to mind. But when Gus, a purple and green dragon, appears in her second-grade classroom, his words about bravery command respect among her 7- and 8-year-olds. “He’s a stuffed animal. The teacher is the only one who can hear him talk. And he talks about what it means to be brave as a reader,” said Logan. Gus, along with the writers of the new Units of Study in Reading, have many new things to say about becoming brave readers. Logan notes that in the previous edition of this unit “it felt as though we would do phonics work, and then that work was not practiced in actual reading. Now we are using the same language found in the phonics units in their reading. They work on decoding. Things are much more aligned and merged now.”

Gus, along with the writers of the new Units of Study in Reading, have many new things to say about becoming brave readers. Logan notes that in the previous edition of this unit “it felt as though we would do phonics work, and then that work was not practiced in actual reading. Now we are using the same language found in the phonics units in their reading. They work on decoding. Things are much more aligned and merged now.”

Logan was part of a group of teachers across the country piloting new Grade 2 Units of Study (UoS). In the updated unit, Tackling Longer Words and Longer Books, new research in reading instruction and better alignment of instructional materials lead students to engage challenging texts with confidence. Regarding phonics, the unit’s coauthors note in their introduction that “children will use and build on everything they learned about vowels across first grade and in prior units this year: vowel patterns with silent e, vowel teams, and vowels controlled by R. They will now apply all that knowledge to help them read and write big words.” To help students make this connection, Gus crosses over from the Phonics units to play a starring role in this new reading unit.

A seasoned teacher of twenty-four years, Logan teaches her class of nineteen students in the North Tonawanda City School District, which is about twenty minutes outside Buffalo, New York. Spruce Elementary School is a Title 1 K–3 school. “It’s a homey neighborhood school in a small city,” Logan said.

Among the many attributes you might assign to teacher Michelle Logan, ‘dragon whisperer’ is not one that might first come to mind. But when Gus, a purple and green dragon, appears in her second-grade classroom, his words about bravery command respect among her 7- and 8-year-olds. “He’s a stuffed animal. The teacher is the only one who can hear him talk. And he talks about what it means to be brave as a reader,” said Logan. Gus, along with the writers of the new Units of Study in Reading, have many new things to say about becoming brave readers. Logan notes that in the previous edition of this unit “it felt as though we would do phonics work, and then that work was not practiced in actual reading. Now we are using the same language found in the phonics units in their reading. They work on decoding. Things are much more aligned and merged now.”

Gus, along with the writers of the new Units of Study in Reading, have many new things to say about becoming brave readers. Logan notes that in the previous edition of this unit “it felt as though we would do phonics work, and then that work was not practiced in actual reading. Now we are using the same language found in the phonics units in their reading. They work on decoding. Things are much more aligned and merged now.”

Logan was part of a group of teachers across the country piloting new Grade 2 Units of Study (UoS). In the updated unit, Tackling Longer Words and Longer Books, new research in reading instruction and better alignment of instructional materials lead students to engage challenging texts with confidence. Regarding phonics, the unit’s coauthors note in their introduction that “children will use and build on everything they learned about vowels across first grade and in prior units this year: vowel patterns with silent e, vowel teams, and vowels controlled by R. They will now apply all that knowledge to help them read and write big words.” To help students make this connection, Gus crosses over from the Phonics units to play a starring role in this new reading unit.

A seasoned teacher of twenty-four years, Logan teaches her class of nineteen students in the North Tonawanda City School District, which is about twenty minutes outside Buffalo, New York. Spruce Elementary School is a Title 1 K–3 school. “It’s a homey neighborhood school in a small city,” Logan said.

Bend 1

Bend 1 lays the foundation for tackling longer words and moving through words methodically, allowing students to utilize their new phonics skills. Working with partners, students create themed “wish bins” of books by sifting through their classroom

library. The categories of books are up to the students.

“There was a basket of books with just pigs as main characters, books that make us laugh. Some made a scary book bin with titles that sounded like they would be scary,” said Logan. “They get to choose. It is kind of a frightening thing for a teacher because we don’t like to give up how we organize our books.”

Instructionally, the new lessons not only help students build strong peer-to-peer partnerships, but they also help students apply research-based strategies when coming across tricky and longer words. Logan noted that the literacy work builds foundational skills, but it is not exclusively about phonics and decoding.

Logan notes that, “You are lifting the level of reading not just with decoding, but you are still engaging students in making meaning. Ultimately, reading is about understanding, reading is about making meaning, reading is about enjoying reading.”

“You are lifting the level of reading not just with decoding, but you are still engaging students in making meaning. Reading is about understanding, reading is about making meaning, reading is about enjoying reading.”

Bend 2

Bend 2 is when second-grade students tackle longer books and chapter books. Small groups take on special importance for those who continue to struggle in basic literacy skills. There were also new challenges which presented themselves as a result of hybrid and online learning experiences during the pandemic. Logan’s students left typical in-person schooling experience in Kindergarten—for some in second grade it was their first full year in school.

“Developmentally, they are just lacking in knowing how to be in a classroom, knowing how the back and forth of conversation works, and when it is appropriate to turn and talk, and the ways you talk with your partner,” said Logan.

There were also basic things that needed to be reviewed such as letters and sounds, basic concepts of print, working left to right when decoding words, and to not rely on picture cues instead of doing the hard work of decoding.

“The kids are still really great,” said Logan. “They just missed a lot academically, socially, and emotionally because of the pandemic.”

Bend 3

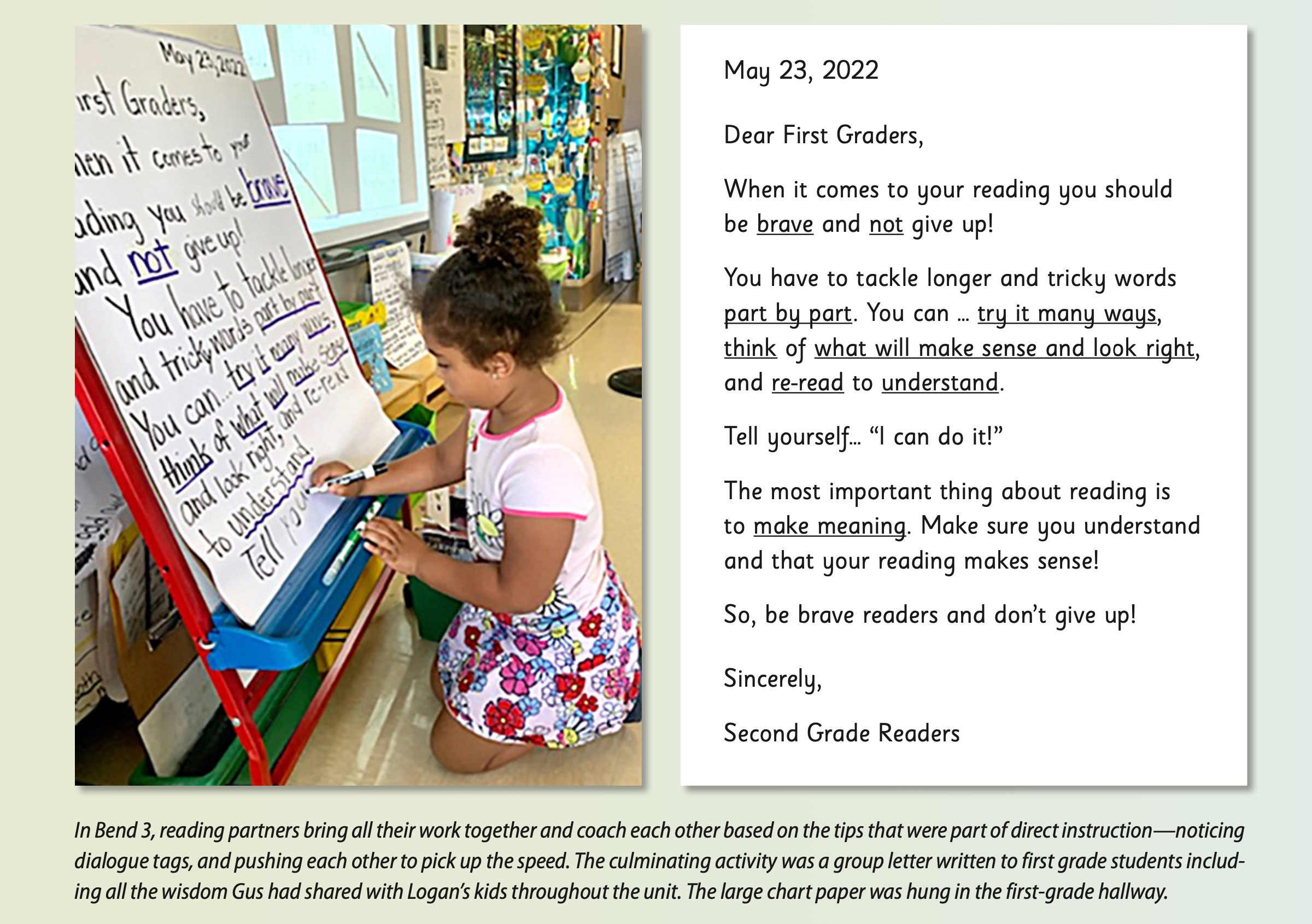

In Bend 3, reading partners brought all their work together to coach each other based on the tips that were part of direct instruction—noticing dialogue tags, and pushing each other to pick up the speed. The culminating activity was a group letter written to first grade students including all the wisdom Gus had shared with Logan’s kids throughout the unit. The letter, written on large chart paper, was hung in the first-grade hallway.

Collectively, Logan appreciated the alignment among the reading, writing, and phonics units. She also noted that the recommendations for read-alouds were much more diverse.

The culminating activity of the Tackling Longer Words and Longer Books unit was a group letter written to first-grade students including all the wisdom Gus had shared with Logan’s kids throughout the unit. The large chart paper was hung in the first-grade hallway.

• • •

About the Writer: Marc Marin has sojourned in education as an administrator and ELA teacher for more than two decades in Fairfield County, Connecticut. He briefly worked alongside his heroes in literacy at TCRWP at Columbia University in New York City before moving to full-time writing, consulting, and teaching. He currently lives in Trumbull, CT with his wife, 3 children, 5 chickens, and 20,000 honeybees. He can be found on Twitter @MarcJMarin.