In today’s linguistically diverse elementary classrooms, research suggests that a universal approach to building academic vocabulary and conceptual knowledge holds huge promise for closing the opportunity gaps among English learners.

Today's blog is adapted from Cultivating Knowledge, Building Language, wherein Nonie Lesaux and Julie Harris present a knowledge-based approach to literacy instruction that supports young English learners’ (ELs) development of academic content and vocabulary knowledge and sets them up for reading success.

What is Oral Language?

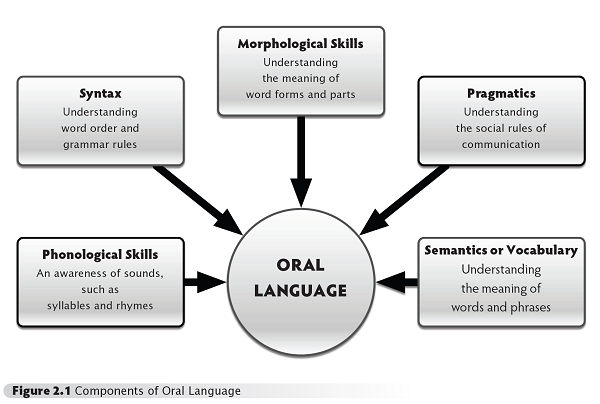

Oral language is the system through which we use spoken words to express knowledge, ideas, and feelings. Developing ELs’ oral language, then, means developing the skills and knowledge that go into listening and speaking—all of which have a strong relationship to reading comprehension and to writing. Oral language is made up of at least five key components (Moats 2010): phonological skills, pragmatics, syntax, morphological skills, and vocabulary (also referred to as semantics). All of these components of oral language are necessary to communicate and learn through conversation and spoken interaction, but there are important distinctions among them that have implications for literacy instruction.

The Components of Oral Language

A student’s phonological skills are those that give her an awareness of the sounds of language, such as the sounds of syllables and rhymes (Armbruster, Lehr, and Osborne 2001). In addition to being important for oral language development, these skills play a foundational role in supporting word-reading development. In the early stages of learning how to read words, children are often encouraged to sound out the words. But before even being able to match the sounds to the letters, students need to be able to hear and understand the discrete sounds that make up language. Phonological skills typically do not present lasting sources of difficulty for ELs; we know that under appropriate instructional circumstances, on average, ELs and their monolingual English-speaking peers develop phonological skills at similar levels, and in both groups, these skills are mastered by the early elementary grades. Students’ skills in the domains of syntax, morphology, and pragmatics are central for putting together and taking apart the meaning of sentences and paragraphs, and for oral and written dialogue.

Syntax refers to an understanding of word order and grammatical rules (Cain 2007; Nation and Snowling 2000). For example, consider the following two sentences: Sentence #1: Relationships are preserved only with care and attention. Sentence #2: Only with care and attention are relationships preserved.

In these cases, although the word orders are different, the sentences communicate the same message. In other cases, a slight change in word order alters a sentence’s meaning. For example:

Sentence #1: The swimmer passed the canoe.

Sentence #2: The canoe passed the swimmer.

Morphology, discussed in more detail in Chapter 7, refers to the smallest meaningful parts from which words are created, including roots, suffixes, and prefixes (Carlisle 2000; Deacon and Kirby 2004). When a reader stumbles upon an unfamiliar word (e.g., unpredictable), an awareness of how a particular prefix or suffix (e.g., un- and -able) might change the meaning of a word or how two words with the same root may relate in meaning to each other (e.g., predict, predictable, unpredictable) supports her ability to infer the unfamiliar word’s meaning. In fact, for both ELs and monolingual English speakers, there is a reciprocal relationship between morphological awareness and reading comprehension, and the strength of that relationship increases throughout elementary school (Carlisle 2000; Deacon and Kirby 2004; Goodwin et al. 2013; Kieffer, Biancarosa, and Mancilla-Martinez 2013; Nagy, Berninger, and Abbott 2006).

Pragmatics refers to an understanding of the social rules of communication (Snow and Uccelli 2009). So, for example, pragmatics involve how we talk when we have a particular purpose (e.g., persuading someone versus appeasing someone), how we communicate when we’re engaging with a particular audience (e.g., a family member versus an employer), and what we say when we find ourselves in a particular context (e.g., engaging in a casual conversation versus delivering a public speech). These often implicit social rules of communication differ across content areas or even text genres. Pragmatics play a role in reading comprehension because much of making meaning from text depends upon having the right ideas about the norms and conventions for interacting with others—to understand feelings, reactions, and dilemmas among characters or populations, for example, and even to make inferences and predictions. The reader has to be part of the social world of the text for effective comprehension.

Vocabulary knowledge must be fostered from early childhood through adolescence.

Finally, having the words to engage in dialogue—the vocabulary knowledge— is also a key part of oral language, not to mention comprehending and communicating using print (Beck, McKeown, and Kucan 2013; Ouellette 2006). Vocabulary knowledge, also referred to as semantic knowledge, involves understanding the meanings of words and phrases (aka receptive vocabulary) and using those words and phrases to communicate effectively (aka expressive vocabulary).

Notably, vocabulary knowledge exists in degrees, such that any learner has a particular “level” of knowledge of any given word (Beck, McKeown, and Kucan 2013). This begins with the word sounding familiar and moves toward the ability to use the word flexibly, even metaphorically, when speaking and writing. Vocabulary knowledge must be fostered from early childhood through adolescence. Deep vocabulary knowledge is often a source of difficulty for ELs, hindering their literacy development (August and Shanahan 2006).

If you would like to learn more about Cultivating Knowledge, Building Language, you can download a sample chapter here:

Nonie K. Lesaux, PhD, is the Juliana W. and William Foss Thompson Professor of Education and Society at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Lesaux leads a research program guided by the goal of increasing opportunities to learn for students from diverse linguistic, cultural, and economic backgrounds. Her research on reading development and instruction, and her work focused on using data to prevent reading difficulties, informs setting-level interventions, as well as public policy at the national and state level.

Julie Russ Harris, EdM, is the manager of the Language Diversity and Literacy Development Research Group at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. A former elementary school teacher and reading specialist in urban public schools, Harris’s work continues to be guided by the goal of increasing the quality of culturally diverse children’s learning environments.