I have spent a lot of time teaching kids how to write graphic novels, teaching educators about graphic novels and comic books, and countless hours reading comics myself. Based on my expertise in this area, I have developed a list of the top three things to avoid when teaching kids how to write graphic novels.

1. Don’t assume every child is familiar with the comic book medium.

Sales of comics and graphic novels rose more than 60% in 2021, according to Milton Griepp, CEO of the website ICv2 which provides news and information for geek culture retailers. Griepp also shares that graphic novels make up more than 70% of the comics market.

Even with this massive growth in the comics market, there are still kids in your class who have never read a graphic novel before. This is why my co-author, Hareem Atif Khan, and I launch our unit with an inquiry into the graphic novel medium.

To prepare for the inquiry, gather a few baskets of graphic novels. If you don’t have a lot in your own personal classroom library, perhaps you could work with your grade level colleagues to create bins of graphic novels that could rotate around the various classrooms launching this unit. If your school has a librarian, I’m sure they would also be happy to help! As a last resort, you could also copy a few pages from the graphic novels you do have. The idea is that each table or group of writers might have a basket of graphic novels to study, perhaps even rotating to different bins depending on your timeframe.

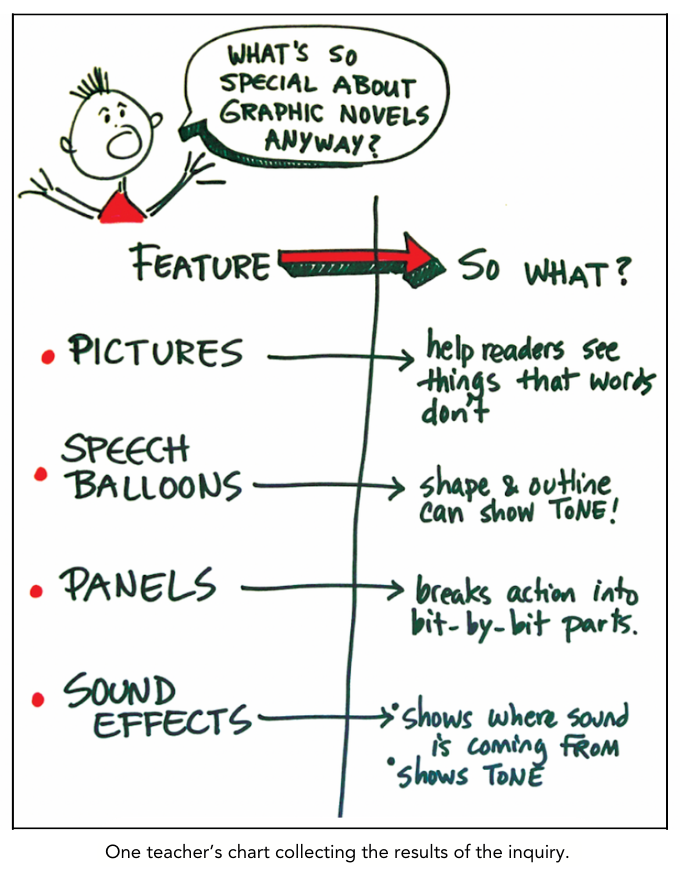

You will want to push your young graphic novelists to do more than just name what they see. One way to do this is to set your inquiry chart up, as you see below, with two columns, “Feature” and “So what?” The question “So what?” is a shortened version of “So what does this feature do?” or “So what effect does this feature have on the reader?”

This inquiry will also be beneficial to the graphic novel aficionados in your classroom. Even kids who read a lot of graphic novels don’t always have a firm grasp on the vocabulary of the form.

To get you started, I’ve collected some important vocabulary for graphic novel readers and creators in the chart below.

The Vocabulary of Graphic Novels & Comics

| panel | A typically rectangular shape that contains the art and text. Each panel represents a moment in time. |

| gutter | The typically white space that separates the panel. Time passes within the panel. This time could be a moment, a day, or a year. |

| emanata | Unrealistic lines or symbols that symbolize something about a character i.e. a sweat drop, heat rays or a question mark by a character’s head Fun Fact: This term was coined by American cartoonist Mort Walker of Beetle Bailey fame! |

| speech balloons | Show what a character says. The shape of the balloon show the expression in which the dialogue should be read. |

| thought bubble | Shows a character’s thoughts. |

Here’s another chart in which the elements of a page are labeled.

By not assuming that all of your writers are already experts of the graphic novel medium, you “level the playing field” and set up all of your writers for success.

2. Don’t limit the narrative genre that kids write within.

Graphic Novels: Writing in Pictures and Words is innovative for a writing unit of study, because it focuses on a medium rather than a genre. In all other TCRWP Writing Units of Study, the lessons teach kids how to write realistic fiction, literary essays, or research reports. This is important, because the writing genre is the nucleus around which the lessons rotate.

In this Unit of Study, however, our nucleus is a medium. The comic book medium, or format, in inclusive of multiple genres. Smile by Raina Telgemeier is a memoir, Amulet by Kazu Kibuishi is a fantasy story, and Leon The Extraordinary by Jamar Nicholas is a superhero story–but ALL of these stories are told in the graphic novel MEDIUM.

There are even non-fiction graphic novels. Hareem and I decided to zoom-in on narrative writing so as to be able to unify the teaching within the lessons more clearly. It would be exciting to think about the ways in which the graphic novel form could be extended into writing about science or social studies concepts after this unit.

During this unit, you might have young writers creating true stories, realistic stories or even fantasy stories.

Here are a few strengths of the new unit:

- It allows for more student choice than other units. They get to choose their own genre. The more choice a student has, the more engaged they will be.

- It provides an opportunity for writers to revisit a favorite genre from earlier in the year. Our scope and sequences are usually bursting at the seams. Very rarely do we have a chance to allow kids to write another fantasy story, if they love writing fantasy. This unit provides the time to do just that!

- It creates the chance for kids to collaborate. Group the kids writing within the same genre together into a publishing house! Publishing houses could support each other as they work on their stories. At the end of the unit, your publishing houses could combine their pieces to create sci-fi or memoir anthologies.

I think it would be a mistake to tell all of your writers to write, for example, realistic fiction stories. By doing this, you remove a facet of this Unit of Study that makes it unique and even more engaging.

3. Don’t limit kids by using pre-printed comic book pages.

I am all for graphic organizers when they are a scaffold and not a limit. When they provide access to a skill that otherwise would be off the table for a writer. The goal is to eventually remove the scaffold, because scaffolding is not meant to be permanent. The wall is meant to eventually stand on its own.

You may feel the desire to give your students pre-designed comic pages. Please restrain this desire. So much of the craft of comics is connected to creating the page. The size, shape, and number of panels on a page contribute to the pacing and emotional impact of the story.

By providing a pre-designed page, you are preventing your writers from making important choices.

Should I start with a large panel to establish the setting or begin on a close-up on the character’s eyes and then zoom out in a series of panels? Should I make this panel lean forward to mimic the action happening with the panel to create some momentum? Should I break the panel here to really show how hard the batter hit the ball?

These are the kinds of questions I want your creators to wrestle with. By asking these questions, they will learn so much about what works (and what doesn’t!) in visual storytelling.

Embrace the imperfection of student-drawn panels. When Hareem and I met with Art Spiegelman, he described a graphic novel as being an artifact in a way that a prose book isn’t, because the creator crafts every part of a graphic novel. It’s much more personal in that way than most prose.

You can provide some support to help your students. You might cut panel templates out of cardstock for writers to trace around. Rulers will also be a big help. Some teachers also used graph paper for their graphic novelists to create their pages. The rows and columns aid them in being neater. If a student has a need, as determined by an IEP or needs OT support, then you should provide whatever will allow access to writing graphic novels.

For most of your students, I recommend that you allow them to fully experience the work of crafting their pages by hand.

Graphic Novels, Grades 4-6, with Trade Pack by Hareem A. Khan and Eric Hand

Eric Hand is a former staff developer at the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project who has taken all his expertise back into the classroom. He has a master’s degree in literacy education and has taught in a variety of classroom settings. While at TCRWP, Eric joined Hareem, Mary Ehrenworth, and others in spearheading efforts to incorporate graphic novels and comic books into Units of Study in Writing. The institute that he and Hareem co-led helped to generate enthusiasm for this important work. Currently, Eric is putting all he knows into action—and he’s learning from his students every day. He regularly posts his learning on his blog, Written by Hand. If you are looking for Eric, check your local comic book shop.