The Science of Challenging Behaviors

The following is adapted from Kids 1st From Day One by Christine Hertz and Kristine Mraz.

Dr. Daniel Siegel, author of The Whole Brain Child, suggests that one way to understand the brain is to think of it as a house, with an upstairs and a downstairs (2011, 38).

The “upstairs” brain—the cerebral cortex—is sometimes called the “thinking” brain and is responsible for more sophisticated functions such as planning, problem solving, empathy, and inhibiting impulses. When you’re planning your next math lesson or figuring out what to cook for dinner, you’re using your upstairs brain. The “downstairs” brain—the amygdala, the brain stem, the limbic region—is responsible for housekeeping duties such as breathing and controlling body temperature, as well as controlling big emotions such as anger and fear. Most of the time you’re not even aware of your downstairs brain, and usually these brain areas work seamlessly together. But stress, in many ways, acts like a locked door to the upstairs brain: the more stress we are placed under, the less access we have to that upstairs brain. There’s actually a reason for the expression “you’ve flipped your lid.” When we get really heated, really emotional, the upstairs part of our brain goes off line and the downstairs part of our brains takes over (Siegel 2011, 39–40). At that moment, our brains tell us to go into flight (storm out of a room), fight (yell, hit, kick), freeze (totally shut down), or flock (seek out the protection of others).

When a child’s downstairs brain is controlling his actions, he is not intentionally choosing to yell at you or bolt out of the classroom. His actions are triggered by a sense of threat—and here the key is to reimagine the word threat—because the threat might just be that the child does not have the necessary social or emotional skills to handle the situation. A child with a low tolerance for distress might interpret “I don’t know how to write the ideas I have” or “It’s time to clean up and I’m not done” or “My friend is mad at me and likely to hate me forever” in a much different way than we would expect. The higher the state of the child’s arousal (the hotter the engine, to return to the metaphor from before), the more she is reacting from her emotional brain rather than her logical brain.

In this moment, remember, unless you have a detached view of the behavior (as in “it’s not about me” and “all behaviors are a form of communication” and not “this child hates me”), you have been placed under stress, too. You are likely not thinking with your upstairs brain, and your anger, frustration, or frozen response means your first response may not be the most helpful or productive one. Take a moment to recite those mantras, take a deep breath, and then address the situation.

Start from a Place of Genuine Curiosity

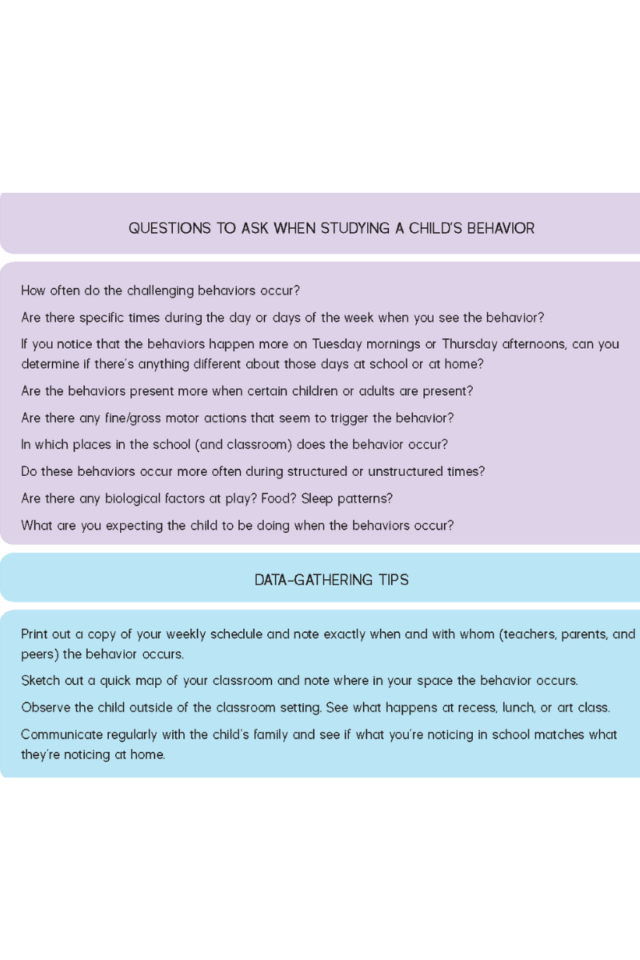

Observe behaviors and gather information. The first place you may want to start when addressing challenging behaviors is by fixing everything right away. We get it. That’s why clip charts, sticker charts, and tally systems are so seductive: they are like hanging a picture to cover a crack in the wall. You may no longer see it, but as soon as you move the picture, the issue is there, possibly even worse than before. Same with challenging behaviors; if we remember that every behavior is a child trying to communicate lack of a skill he is compensating for, then it’s much more helpful in the long run, for the benefit of the child’s life in society, not just in our classroom, to determine what he’s trying to communicate. Just as a child who is struggling with place value isn’t going to necessarily say to you, “Gee, I could really use some help understanding the value of this digit,” children struggling with behavior aren’t going to say, “FYI, transition times are really tricky for me. I have a hard time going from one thing to another.” We can start, then, by observing closely and asking ourselves and our colleagues questions.

Develop a Plan

Once you sit down to answer some of those questions and really observe your student, you’ll start to notice patterns and specific lagging skills. Maybe angry outbursts occur when there is a “zigzag” to the plan and the child has difficulty with flexibility. Perhaps a child has a hard time following directions when you just give them as spoken commands with no visuals. Or maybe a child hits another child when she feels left out or rejected. As in all aspects of teaching, pick a specific skill and a strategy to try first.

A quick note: the best time to start this conversation is not when you feel your own engine overheating. We are all human, we all have immediate reactions, we all react and overreact. Take a moment to breathe deeply, vent out your feelings of frustration privately, and then begin. You cannot help a child develop better community skills by forgoing your own modeling of behavior. We will have more to say about this in a minute.

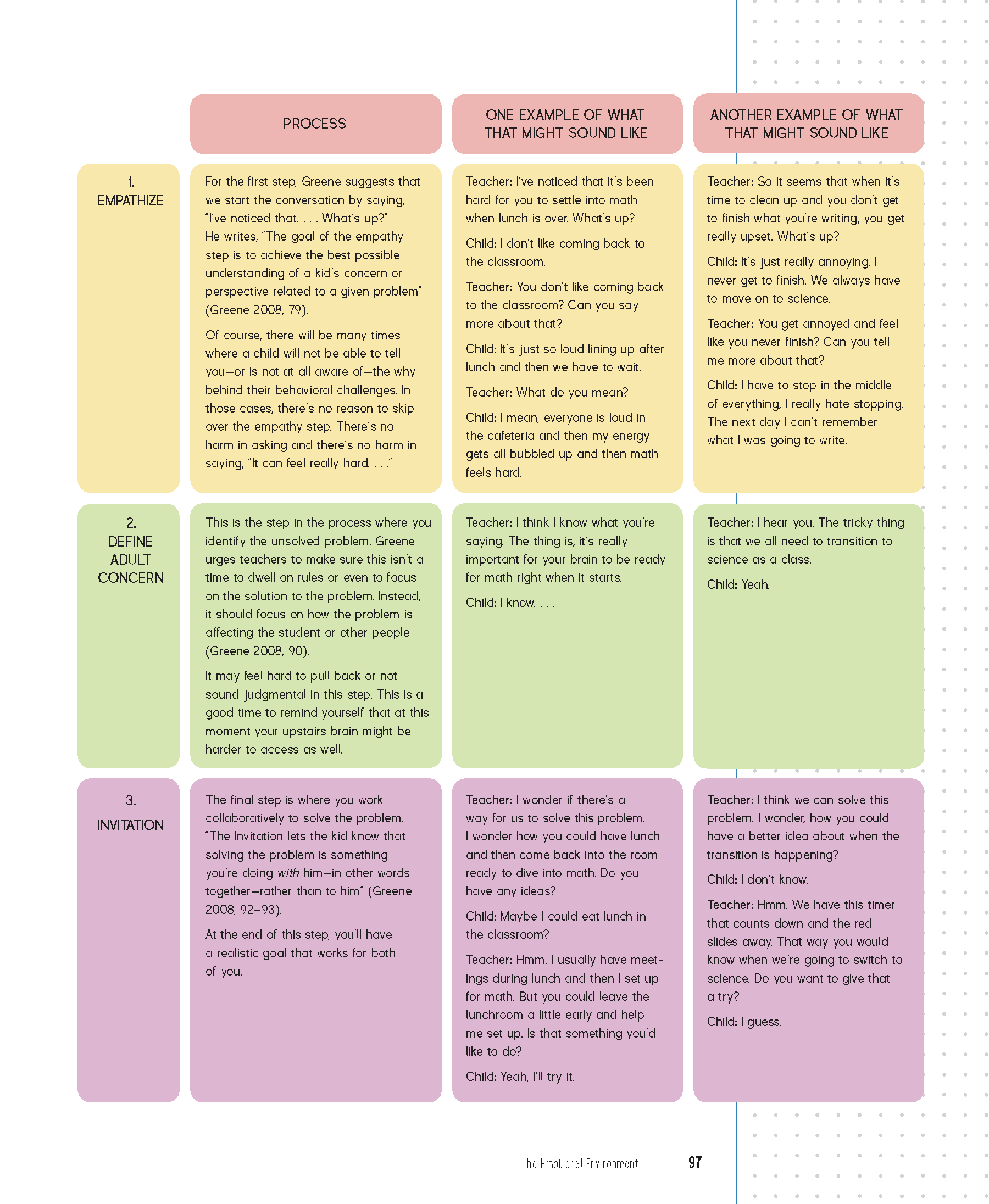

Ross Greene (2008, 78) recommends three steps for solving these unsolved problems:

- Empathize with the student.

- Define adult concerns.

- Offer an invitation.

This process might look familiar to those of you who confer and set goals with children.