The most frequently taught elements of argument are the initial work of developing claims, reasoning, and evidence. Here, we’d like to take the work a bit deeper, focusing on what we’ve come to consider the parts of this process that are most crucial for developing ethical citizens—listening, revising our thinking, responding to rational counterarguments, and acknowledging complexity and conditionality. This work is important for an engaged citizenry. It’s also good for kids. When kids learn to listen, they become more nuanced. When they learn to listen, they see each other and the world in more empathetic ways. And others respond to them differently as well.

To teach kids to value listening as part of the process of research and argumentation, you have to create a paradigm in which kids are not learning to argue, or arguing to win, but instead, are arguing to learn. If you and your class enter into argumentation with the idea that everyone will learn from those whose positions differ, then your students will be willing to accept different points of view more gracefully—and perhaps even change their own. Launch your work, then, by explaining that the mark of a sophisticated thinker is the willingness to revise their thinking. This is different from the urge to dominate, to win. Your students will instead strive to teach and to learn.

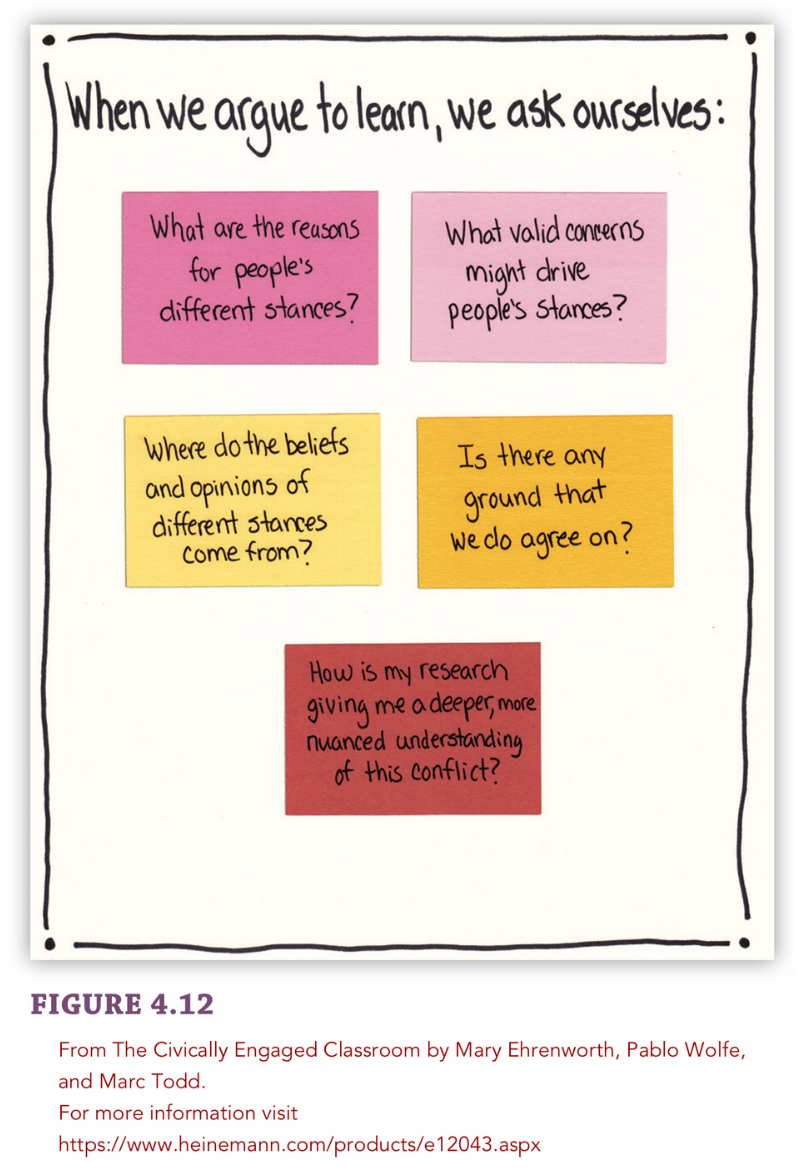

There are some central questions you can teach students to pose as they strive to become ethical researchers and arguers. To be ethical means you don’t hide from conflict and you don’t override complexity, but, instead, you seek out diverse points of view and honestly try to understand what informs those viewpoints. It can be helpful for students to pose critical questions, of themselves and others, to help them develop their arguments and hear others’, see some examples in Figure 4.12.

As we strive to help students become better listeners, we do not ask them to empathize with every viewpoint they encounter. Some arguments are ones where you can’t settle on a middle ground.

However, students can practice listening to alternative points of view and even to points of view that diverge inside of coalition teams: disagreements not about whether racism is bad or good but about which ways to combat racism are the most powerful; disagreements not about whether we should explore green energy but about the most effective ways to promote green energy or protect the climate. These interior debates are far more nuanced than simply labeling one side good and another bad. They also involve careful listening.

Listening, we’ve found, can mean listening actively as you read, and listening actively to others as you debate and argue. Here are some protocols to strengthen students’ listening skills and openness.

Engaging in Low-Stakes Social Arguments

One way to help young people understand that listening is an important part of compelling argumentation is to engage them in practicing small, low-stakes social arguments about causes that are dear to their hearts; for instance, asking their parents for a dog or for a later curfew, or to be able to drive the family car, or asking friends to change in some way. When you give kids the opportunity to practice personal, low-stakes arguments, and they try them out at home or on their friends, taking time to work on addressing counterarguments gracefully, you teach kids to listen to opposing viewpoints and to respond to them respectfully. This is a significant life skill. Often kids report back that they “didn’t get the dog,” but that over time, the dynamics in their relationships changed, and they feel more listened to. What has really happened is that they are now more listened to because they are better listeners.

Starting with Hypotheses Rather Than Claims

In the last few years we’ve done a lot of work collaborating with both science teachers and working scientists on argumentation, especially related to the climate crisis. One thing that scientists have suggested to us is that working scientists don’t start with a claim—they start with a hypothesis, even when they are publishing peer-reviewed journal articles about their research. They pose a hypothesis and then show how they have tested out that hypothesis. They’re careful to show when their suppositions played out strongly, and when their evidence was less compelling or more opaque. They often explore the boundaries or conditions under which their hypothesis seems most true. These are helpful protocols in any discipline, and you can guide your kids to begin, in any argument process, with a hypothesis. The same principle works in ELA or Social Studies classes, when kids begin with a hypothesis (“It seems likely that. . .”) and then test out their idea through the act of writing and/or research.

Developing Rituals for Complimenting Your Opponents’ Best Points

Whenever your students are about to engage in a debate or a debate-like discussion, let them know that, after the exchange, they will be telling their opponents which points they found most compelling, and why. When students know that they will need to describe their opponents’ best point, they begin to take note when their opponent speaks. When they also practice complimenting, they learn to recognize and respond to the nuances of opposing viewpoints.

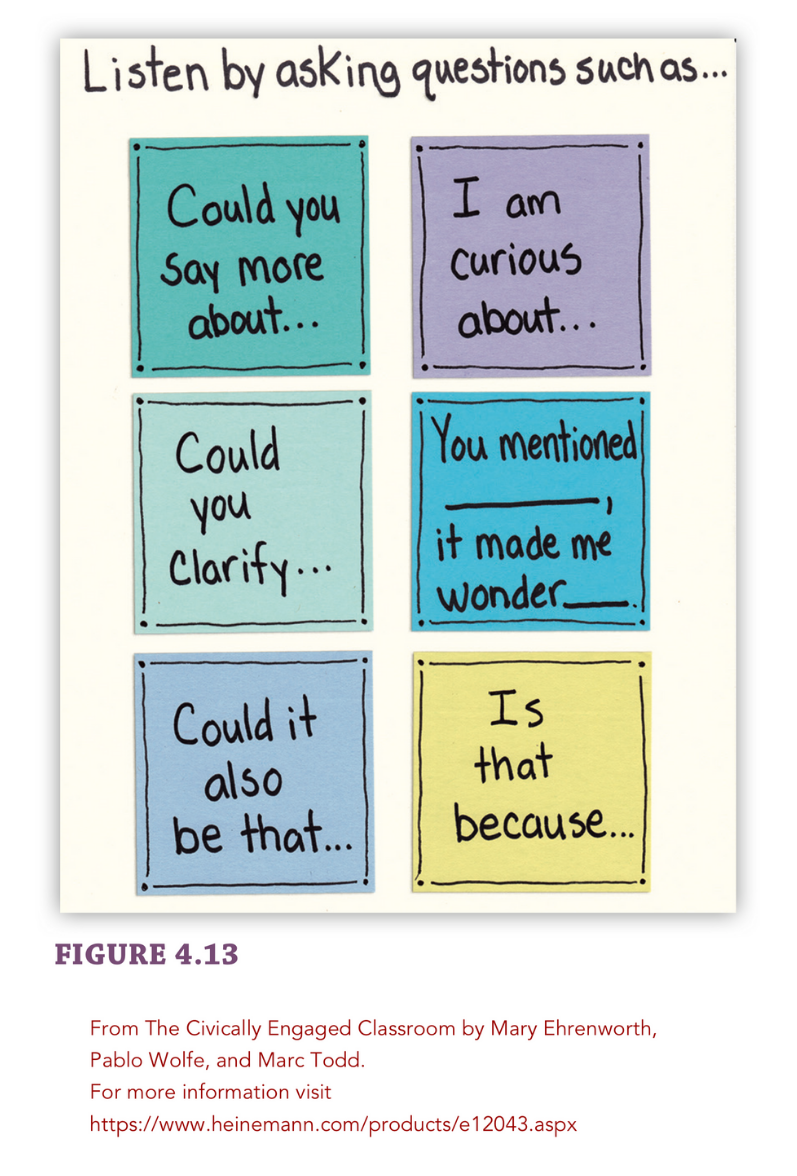

Questioning as a Way of Listening

Teach students graceful questioning, the kind of questioning that you can only do if you have been listening carefully. Suggest that they jot notes as they listen, and prepare to probe more deeply, not to override but to understand better. Some helpful sentence starters might include those shown in Figure 4.13. Considering Counterclaims with Thought-Partners

Considering Counterclaims with Thought-Partners

Giving kids time to work together to consider counter claims and to develop their own responses increases students’ openness to complexity. First, it helps kids to recognize that there are counterclaims and to consider their validity. Second, it helps them see that many topics are complex and there are rational aspects to opposing sides. Third, it helps kids develop rational and responsive refutations to counterclaims so that instead of simply restating their positions, they respond to the points brought up by the other side.

Considering Conditionality

Encourage students to ask themselves, “Under what conditions does my argument most hold true?” Putting constraints on a position can make it stronger, a significant lesson for young argument writers.

Listening for Fallacies

Teach students to first listen for some of the most predictable logical fallacies and then to work to make their arguments more ethical and to call out less-than-logical techniques. (See Chapter 3 of The Civically Engaged Classroom for guidance in teaching students about logical fallacies.)

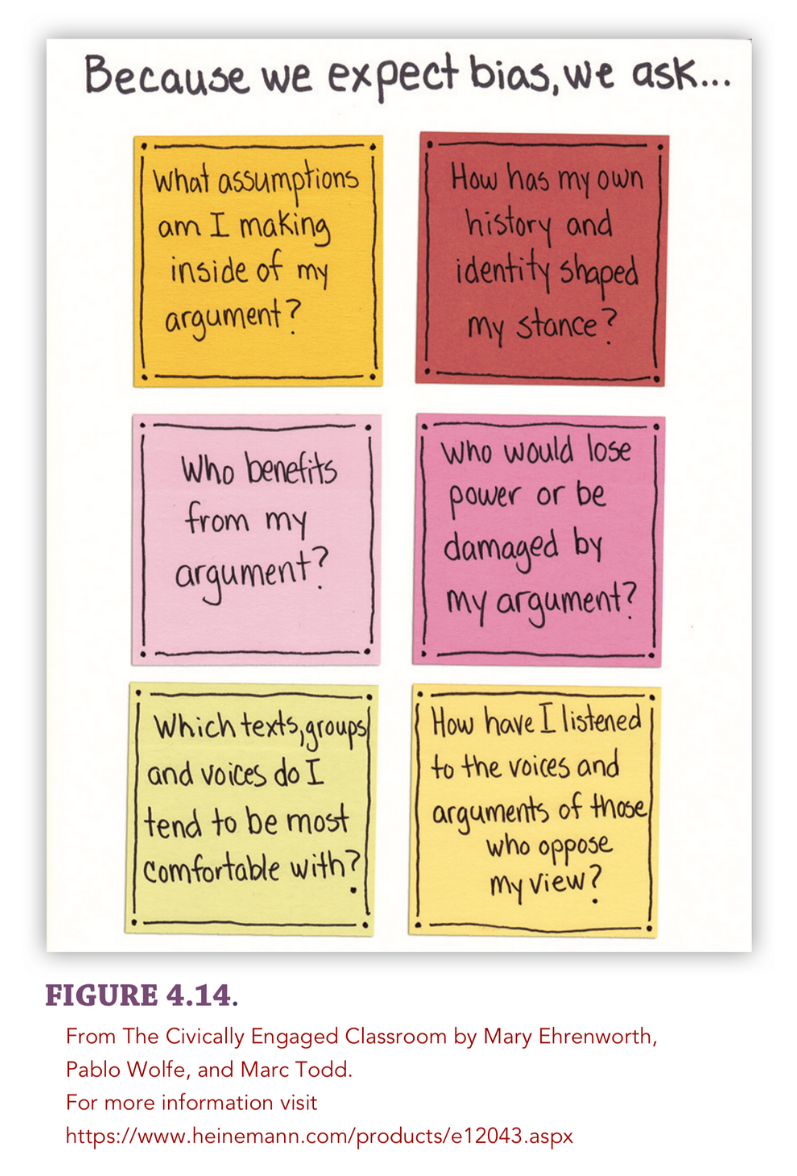

Listening for Bias of All Kinds

We’re all biased, all the time. But we can listen for and reflect on bias that seeps into our arguments. Some questions that can help students tackle this work include those shown in Figure 4.14.

To learn more about this book visit Heinemann.com.

👉 Watch Laying the Groundwork for A Civically Engaged Classroom: A Video Series

Mary Ehrenworth, Senior Deputy Director of the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project and co-editor for the Units of Study for Teaching Reading, Middle School series, works with schools and districts around the globe, and is a frequent keynote speaker at Project events and national and international conferences. Mary’s interest in critical literacies, deep interpretation, and reading and writing for social justice all inform the books she has authored or co-authored in the Reading and Writing Units of Study series as well as her many articles and other books on instruction and leadership. You can connect with her on Twitter @MaryEhrenworth.

Mary Ehrenworth, Senior Deputy Director of the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project and co-editor for the Units of Study for Teaching Reading, Middle School series, works with schools and districts around the globe, and is a frequent keynote speaker at Project events and national and international conferences. Mary’s interest in critical literacies, deep interpretation, and reading and writing for social justice all inform the books she has authored or co-authored in the Reading and Writing Units of Study series as well as her many articles and other books on instruction and leadership. You can connect with her on Twitter @MaryEhrenworth.

Pablo Wolfe is a Washington DC-based educator who promotes civic education as a means to improve student engagement, celebrate student identity, and embolden the next generation of activists. He's been a public school administrator, a staff developer with the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, a teacher, and a parent, and in all of these roles has sought to make school a training ground for civic life. Whether planning town hall meetings with groups of 7th graders, writing letters to elected officials, or organizing opportunities for service learning, Pablo believes that academic skills are best learned when applied towards addressing social injustices. He is currently working to create a network of civic-minded educators to share stories and best practices that illustrate how civic knowledge, values, and behaviors improve student outcomes and transform schools. A strong believer in the role of teachers as agents of social change, he strives to thread this idea through his writing, staff development and teaching. You can connect with him on Twitter @pablowolfe.

Marc Todd teaches Social Studies at IS 289, the Hudson River Middle School in New York, and is a national presenter for the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. He collaborates with teachers around the world and leads workshops and institutes on culturally relevant pedagogy and teaching students to be critical readers of history. Marc believes in immersing kids in nonfiction reading and making notebook work inside of content classes both serious and joyful.

Marc Todd teaches Social Studies at IS 289, the Hudson River Middle School in New York, and is a national presenter for the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. He collaborates with teachers around the world and leads workshops and institutes on culturally relevant pedagogy and teaching students to be critical readers of history. Marc believes in immersing kids in nonfiction reading and making notebook work inside of content classes both serious and joyful.

You can connect with him on Twitter @marctoddnyc.