This post is adapted from No More Teaching A Letter A Week by Rebecca McCay and William Teale.

How Many Letters and Letter Sounds Should Young Children Know, And By When?

This question becomes important in light of the differing standards for alphabet knowledge that can be found for preschoolers:

- Alaska, Alabama, Arizona, South Dakota—at least 10 letters

- Indiana—13 uppercase letters

- The Head Start Outcomes Framework—“Identifies at least 10 letters of the alphabet, especially those in their own name”

- Early Reading First Performance Targets—16 to 19 letters.

You get the picture—standards for alphabet knowledge vary considerably.

What does research say about what standards should be?

There is as yet no comprehensive answer to this question, in part because the question itself is multifaceted: Is it how many to be considered not at risk? To be successful in reading at third grade? At first grade? And so forth… It is also the case that few studies have addressed this question directly. The best indicator we have to date comes from research conducted by Piasta, Petscher, and Justice (2012). They investigated the diagnostic efficiency of various upper- and lowercase letter-naming standards for 371 preschoolers, and one particular question in the study attempted to identify “optimal benchmarks.” Findings indicated that an end-of-preschool/beginning of kindergarten benchmark of ten letters was adequate to determine negative predictive power (the vast majority of children reaching this benchmark would not be at risk for low literacy achievement in grade 1), but also that optimal benchmarks were eighteen uppercase letters and fifteen lowercase letters when considering the three later grade literacy outcomes of letter–word identification, spelling, and passage comprehension. Thus, Piasta, Petscher, and Justice (2012) advocate setting higher end-of-preschool benchmarks than those typically appearing in state early learning standards or Head Start standards.

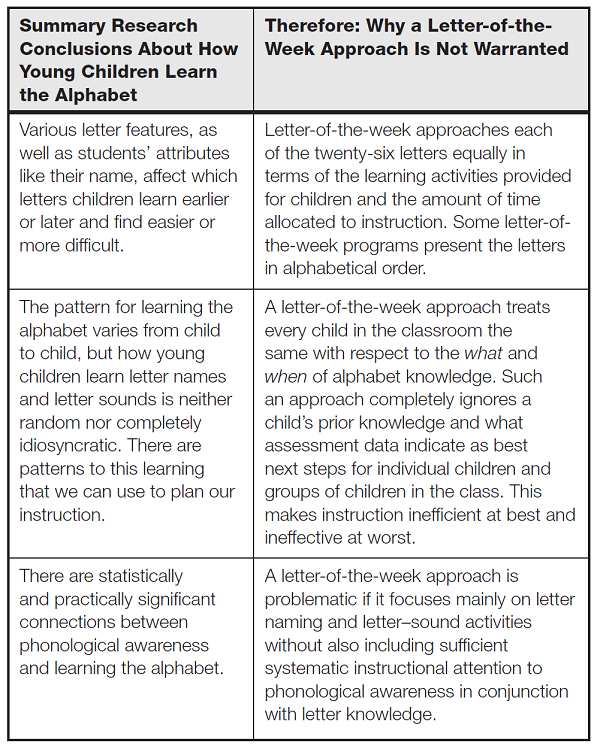

Overall conclusions based on research about how young children learn the alphabet are outlined in the figure below.

William Teale is Professor, University Scholar, and Director of the Center for Literacy at the University of Illinois at Chicago. His work was central to bringing forth the concept of emergent literacy, and he has published widely in the field for the past 35 years.

Former Teacher of the Year in Alabama, Rebecca McKay is a literacy coach, a Teacher Consultant for the National Writing Project, a former trainer of trainers for the Alabama Reading Initiative, and a national presenter on a variety of literacy topics.