Words Matter: Language That Fosters Flexible Thinking by Chris Hall and Mike Anderson

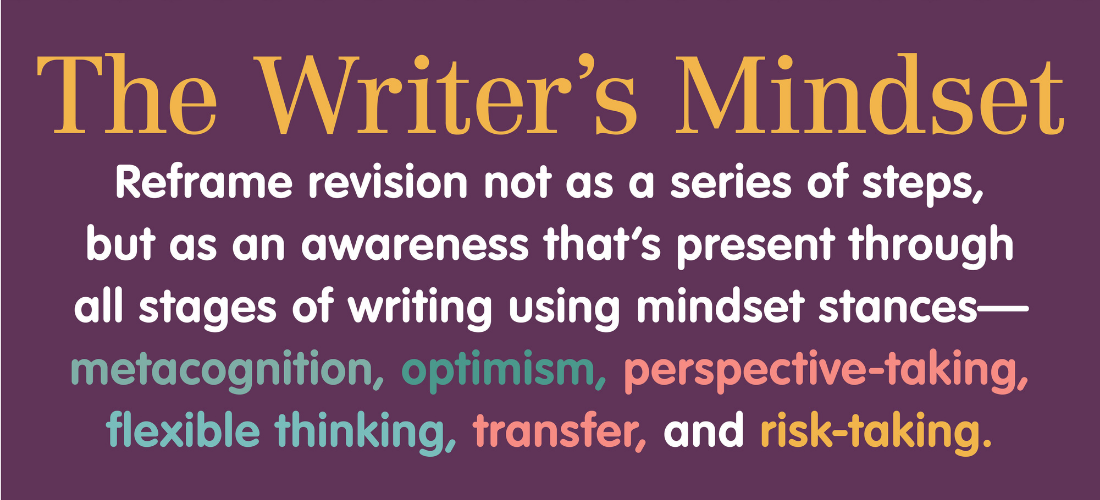

As writing teachers, we want to foster flexible thinking in our students: we want them to be open to new approaches and ideas as they revise. We want each of our young writers to consider what their draft needs, not rush to complete it. To have the confidence to experiment and try something novel and creative with their writing – but also the humility to know that great ideas might come from listening to others. We want them to have the curiosity to seek out fresh solutions to make their writing the best it can be.

One way that we can encourage flexibility and openness is through the language we use as teachers. Our words matter, perhaps more than anything we do. The language we use as teachers can reinforce our core beliefs about writing and revision, or it can inadvertently send the wrong message. We–Mike and Chris–have certainly found ourselves in our own teaching slipping into language patterns that undermined, rather than supported, our best intentions. Here are a few you might consider.

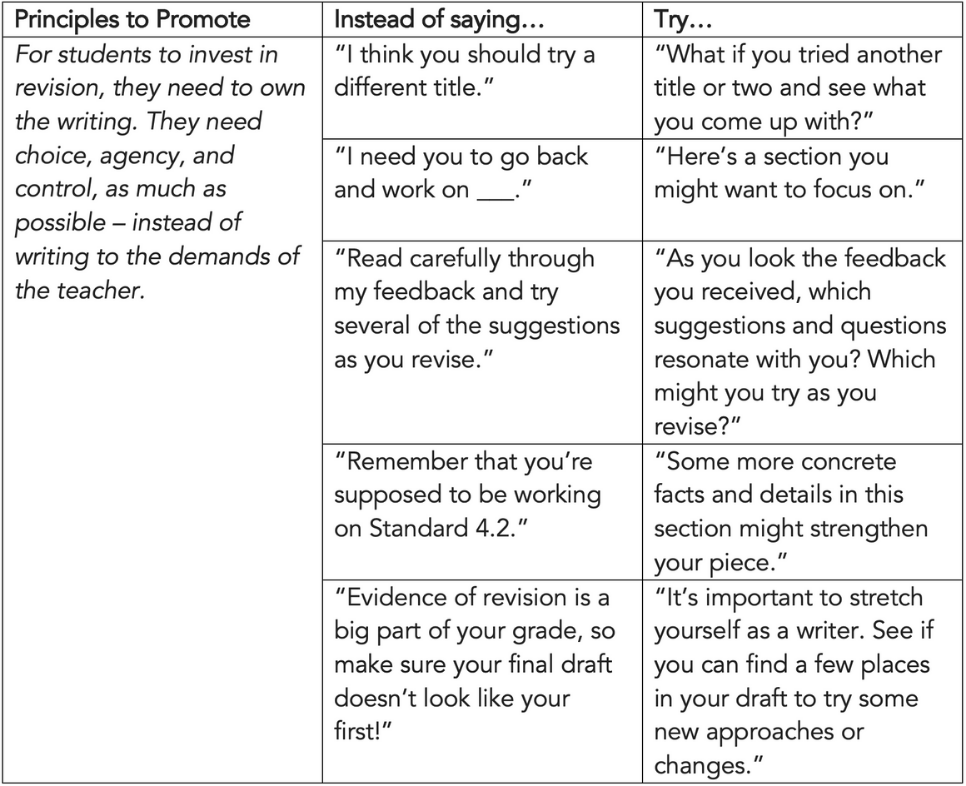

Use Language that Encourages Student Ownership

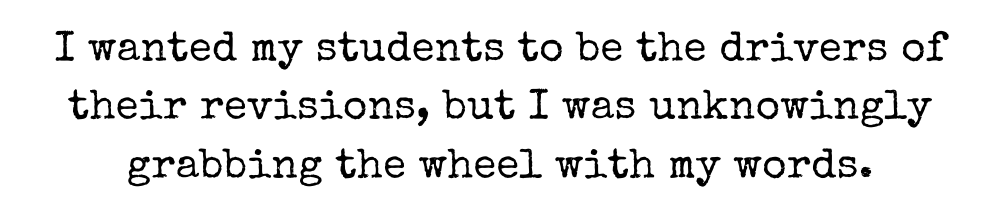

If we want students to be flexible as writers, they need to feel invested and self-motivated. They need the lion’s share of autonomy and control. This is one of the foundational ideas of a writing workshop, and of course, as teachers, we want our students to feel a sense of agency.  Yet, without meaning to, we might accidentally give students the idea that revision is about compliance or writing for some outside demand. We want students to be flexible thinkers as they revise, but that shouldn’t mean flexing just to meet our suggestions. I (Chris) have found myself in writing conferences saying, “I’m looking for you to…” – only to realize the message I was sending: this meeting (and piece) is about my ideas, not yours. There was nothing wrong with offering my perspective, of course, but my default into teacher-centric language emphasized that I was the one in control. I wanted my students to be the drivers of their revisions, but I was unknowingly grabbing the wheel with my words. Likewise, when we overemphasize grades or standards, we can inadvertently make these the motivators for revision, rather than our students’ genuine, intrinsic desire to make changes because they care about the piece.

Yet, without meaning to, we might accidentally give students the idea that revision is about compliance or writing for some outside demand. We want students to be flexible thinkers as they revise, but that shouldn’t mean flexing just to meet our suggestions. I (Chris) have found myself in writing conferences saying, “I’m looking for you to…” – only to realize the message I was sending: this meeting (and piece) is about my ideas, not yours. There was nothing wrong with offering my perspective, of course, but my default into teacher-centric language emphasized that I was the one in control. I wanted my students to be the drivers of their revisions, but I was unknowingly grabbing the wheel with my words. Likewise, when we overemphasize grades or standards, we can inadvertently make these the motivators for revision, rather than our students’ genuine, intrinsic desire to make changes because they care about the piece.

Instead, we can consciously try invitational language that emphasizes student ownership and voice.

Use Language that Encourages Discovery

One of the joys of writing is that moment when your writing takes an unexpected turn. “Where did that idea come from?!” you wonder. We want students to remain open to these moments of epiphany and surprise. As Robert Frost said, the “delight is in the surprise of remembering something I didn’t know I knew.” We want students to see that writers often make these discoveries through the writing process – that new insights often come as we’re writing, not as a precursor to it. Our language can remind students to keep an eye out for these fresh insights – that their best title might be the last one they brainstorm. That they might discover the heart of their piece at the end of the writing process. That we might suddenly realize – mid-draft – that changing the verb tense or the point of view is just the thing our piece needs.

Yet how often, in an attempt to make a messy process feel tidy, do we make the writing process sound linear? “First you plan. Then you draft, revise, and edit. Then you publish.” When we make revision sound like it’s simply one fixed step in the process instead of an ongoing and dynamic element of writing, students can miss the chance to follow their curiosities and find the unexpected.

Use Language That Promotes Play and Growth (and Dials Back Judgment)

Flexible thinking requires vulnerability and risk-taking, and these things are almost impossible when we’re in a place of self-judgment.

Don Murray used to talk about the challenge of turning off his internal censor—that voice in our heads that whispers worries as we write. (“Is this good enough?” “That’s a dumb idea.” “This doesn’t make any sense.”) This is one of the reasons that writing can feel so debilitating at times—a writer’s anxiety can get the in the way of getting into the flow of writing.

So, we need to be careful that we’re not accidentally upping the emotional ante or triggering their inner self-critic as we encourage our students. I (Mike) have started lessons saying, “Good writers…” when modeling certain behaviors or craft moves, but language like this can place students in a position of self-judgment and fixed identity. Yikes—I don’t do that in my writing, our students might worry. I guess I’m not a good writer.

Sometimes our words might prompt kids to critique their work too early in the process, when their ideas are still forming. We want students staying in the flow of writing, not pulling back to assess with a critical eye while their text is just starting to take shape. Without intending to, we might make revision sound like it’s about fixing mistakes or errors – like hunting for something we’ve done wrong as writers.

So let’s strive for language that reinforces play, experimentation, and growth with our emerging drafts. We want our students to be open and flexible with making revisions, but even a few modest changes can be a lot. It can feel vulnerable to make the smallest of changes to a draft.

We want our students to be open and flexible with making revisions, but even a few modest changes can be a lot. It can feel vulnerable to make the smallest of changes to a draft.

The same is true for revising the words we use as teachers.

Making changes to our language can feel overwhelming. Language is part of everything we do, so it can feel threatening to examine something so tied to our identity as educators. It’s natural to hew to certain patterns with our words – and we wouldn’t want to move through our days questioning every word that escapes our lips – but perhaps consider a change or two.

The words we use to talk about writing and revision matter. Which of your words closely match your beliefs, and which might unknowingly run counter to them? As you look to the year ahead in your writing workshop, consider some small but significant language shifts to help your students stay flexible and open-minded as they revise.

Learn more about the The Writer's Mindset on Heinemann.com.

Browse more blogs featuring The Writer's Mindset here, including this podcast.

|

|

Connect with Chris Hall and Mike Anderson on Twitter