Teach students about the impact that stress has on their brains and bodies by giving them language for the why behind their feelings: Introduce the terms sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous system, and discuss how both parts of the nervous system influence the way we feel.

The SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM (Downstairs Brain) controls our fight-flight-or-freeze response. When this part of the nervous system is engaged, we feel physical sensations such as a fast heartbeat, sweaty palms, tense muscles, quickened breathing. We’re ramped up and ready to go (fight), to run away (flight), or to shut down (freeze), depending on our perceived threat. It’s hard for our brains to think clearly, let alone learn, in this state (Harvard Health Publishing 2011).

The PARASYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM (Upstairs Brain) is our “rest and digest” system, responsible for making us feel calm and at peace. This is the system we tap into during meditation, yoga, deep breathing, and other relaxation exercises. When we engage our parasympathetic nervous system, we lower our blood pressure, slow our breathing, and create physiological conditions that promote higher cognitive functioning (van der Kolk 2014, 79; Shulman 2018, 95).

A common metaphor for understanding the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems comes from trauma scientist Dan Siegel, who describes the former as the “downstairs brain” and the latter as “the upstairs brain” (Souers and Hall 2016, 31). In our upstairs brain, we engage in executive functioning—reasoning, analyzing, thinking, learning, planning, dreaming, imagining, inhibiting impulses. But grief, stress, and potentially traumatic experiences often throw us into our downstairs brain, which makes it quite challenging to achieve any of these tasks.

Both our upstairs and downstairs brains are crucial to survival. They carry their own unique wisdom, alerting us to situations that are challenging or potentially dangerous. When working with kids, it’s important to emphasize that the downstairs brain is not bad, nor is the upstairs brain ideal. We need to listen to and integrate both.

Sometimes, though, the downstairs brain overdoes it. It can be perfectionistic and doesn’t always know when it’s time to leave the party. When this happens, and the sympathetic nervous system is stuck in overdrive, students might exhibit a range of behaviors that are, essentially, creative adaptations meant to fulfill a need or manage pain (e.g. connection-seeking or avoidance behaviors, demonstrations of perfectionism or apathy, physical health complaints, increased arousal or aggression, etc.). In such moments, it’s helpful for students and teachers to have strategies on hand to facilitate regulation and co-regulation; de-escalation; and restoration. By grounding and centering ourselves and each other, we steer clear of punitive disciplinary strategies that perpetuate a deficit lens and risk further harming impacted students, and we make space to honor the ingenuity with which students have adapted to loss contexts, the assets and resources that they bring into the learning space (which can, itself, be a place and source of loss and/or trauma, especially for students with marginalized identifiers not reflected or equitably represented through the structure and content of the classroom environment).

| Important Note: In discussions about regulation, it’s critical to simultaneously employ an equity-centered lens; consider the ways in which definitions or perceptions of “regulated behavior” may intersect with specific cultural codes (and perpetuate assimilationist narratives); the contexts from which students losses may be born; and employ consistent, integrated practices geared toward antibias, antiracist work and grief-responsive teaching, not merely through “one-and-done” activities but wrap-around systems of support. There is much critique of the ways in which mindfulness, for example, might feel offensive in the context of loss and/or inequity. We can’t “deep breathe” our way through systemic injustices, and it would be offensive to imply any iteration of that message in our work with students. Instead, re-frame regulation as a state from which systems-change occurs, revealing to students how their personal regulation strategies (reflected upon in the Brain Building Activity, for example) help alleviate some of the physical impacts of stress so that their brains and bodies can reach a state in which they hold the most power to engage in conversations about, and activism around, the equity issues they care about. Centeredness allows us to serve as co-conspirators. |

Regulatory strategies might look different for every student, especially because the behaviors born out of the downstairs brain occur on a broad spectrum, but there are a number of ways we can all work to access our upstairs brains when we’re feeling stuck in our brain basements, each strategy a rung of the ladder.

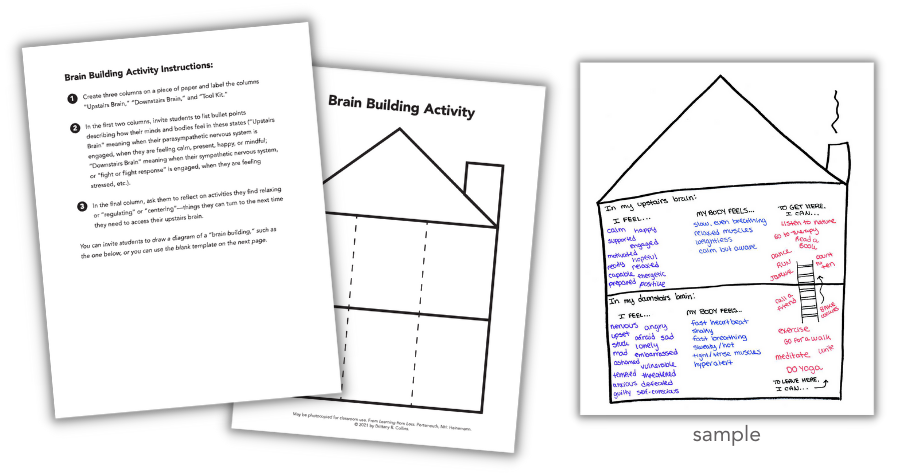

To help students identify ways they can access their upstairs brain, even in times of stress, try this Brain Building Activity. Take a look at the student example and then download the blank version. Use it yourself or with your PLC first, then try it with students.

Click here or the image above to download the Brain Building Activity. Click here to view the sample.

Visit Heinemann.com to learn more about Learning from Loss.

![]()

Brittany Collins is an author, educator, and curriculum designer dedicated to supporting teachers’ and students’ social and emotional wellbeing, especially in times of adversity. Her work explores the impacts of grief, loss, and trauma in the school system, as well as how innovative pedagogies—from inquiry-based learning to identity development curricula—can create conditions supportive of all learners. She is the Founder of Grief-Responsive Teaching, a professional learning community and resource hub that supports students' and teachers' wellbeing in times of loss.

Brittany is passionate about connecting theory and practice to foster collaborative relationships with students, teachers, and writers around the world. She is the Director of Teaching & Learning and Product Manager of Global Writing Workshops at Write the World LLC, where she designs, develops, and implements original writing curricula and supports middle and high school students and teachers across continents.

Her writing has appeared in The Washington Post; Education Week; Edutopia; Inside Higher Ed; We Need Diverse Books; English Journal and Literacy & NCTE of the National Council of Teachers of English; Teachers’ and Writers’ Magazine; and Thrive Global, among other outlets, and she has developed curricula for PBS Learning Media, Write the World, Smith College, Boston University, and Race Project Kansas City, among other schools and organizations.

Brittany studied English and Education at Smith College and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Creative Nonfiction at the Yale Writer’s Workshop; and is pursuing her certificate in Trauma Studies from the Trauma Research Foundation. You can connect with Brittany on her website.