In Teaching Literature In The Context Of Literacy Instruction, coauthors Jocelyn Chadwick and John Grassie explore how the familiar literature we love can be taught in a way that not only engages students but does so within the context of literacy instruction, reflecting the needs of today’s classrooms. They address complex questions secondary English teachers wrangle with daily: Where does literature live within the Common Core’s mandates? How can we embrace informational texts in our literature classrooms? And most importantly, how can we help students recognize how canonical works are relevant to them?

In today's blog, the authors discuss the task of making informational texts engaging inside of a literature classroom.

Embracing Informational Texts In Literature Classrooms

by Jocelyn Chadwick and John Grassie

Quite recently, I was asked to talk about and introduce Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass to a class of high school boys at Woodberry Forest School, in Virginia. However, I can never focus on a single author in isolation—one cannot discuss any text, particularly a personal narrative or an autobiography, without exploring the period, the literature, the concerns, and the people who might have had some impact on the writing. So I decided to include complementary texts, events, and people that affected Douglass and discuss them in light of his personal narrative.

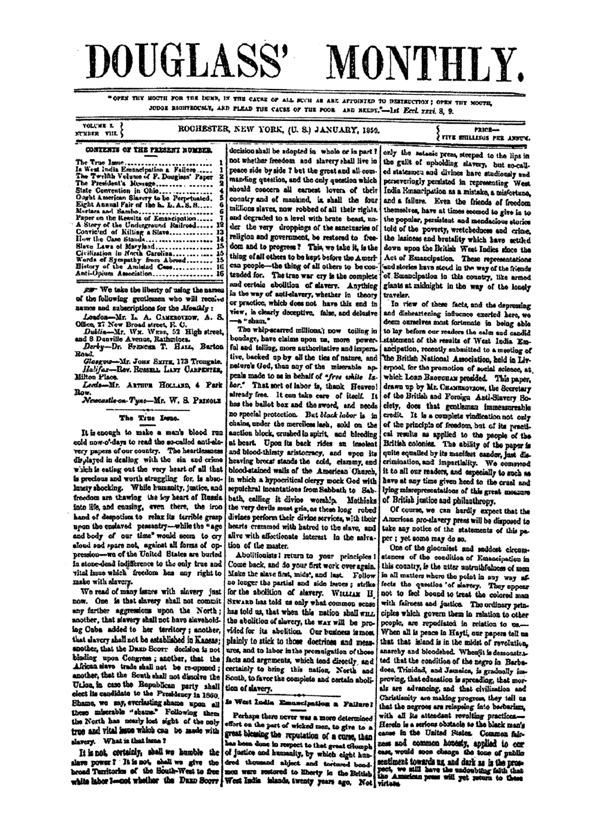

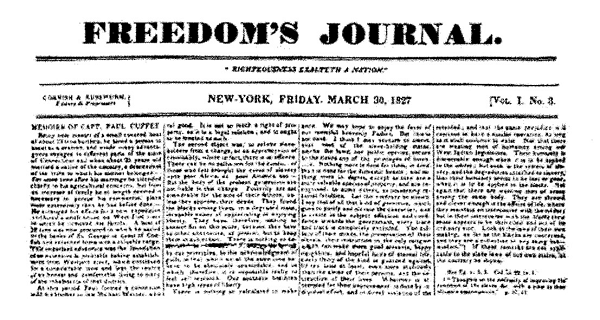

In addition, I had to think about my audience—high school boys—and the school’s classical instructional approach. To complement, even clarify, Douglass’ personal narrative, I included one primary example from Douglass’ Monthly, a journal he published from 1858–1863; a primary source example of Freedom’s Journal, an excerpt from Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1827), and excerpts from Emerson’s “The American Scholar” and “Self-Reliance.” My rationale for blending these specific texts was that Douglass’ narrative is at once autobiography and slave narrative and American success metaphor.

But who was this man—what inspired him to act, to be an activist, to refuse to give up in the face of seeming and real insurmountable challenges, especially at a time in U.S. history when the country itself was groaning, stretching, and careening into a spasm that would literally break apart the country and its people? My instructional goal was to bring this scene, this moment, to the students, using these blended texts—both literary and nonfiction/informational. I hoped that by experiencing them, the students would have questions, would be curious, and would want to know more—enough to read the autobiography in its entirety. It was an amazing experience for me, for the students, and for their teacher.

As we sat in a circle, I asked:

Me: So what is your initial impression of Frederick Douglass?

Student 1: Well, he had a hard time and escaped from slavery.

Student 2: He was unique, right, because he could read and write and was a slave?

Student 3: I really like him.

The remaining comments conveyed similar sentiments. My students at Irving High School in the late 1970s and early 1980s offered similar responses at the beginning of the year, as do the students I encounter throughout the country today. This reluctance is partly because I am new to their classroom; it also stems from the way students and many adults read in the twenty-first century—scanning, taking the text in chunks, instead of experiencing it. (Henry James, who advised readers to engage a text, particularly his own, in little bits, would be shocked and dismayed.)

I then asked the students what else they knew about this period in American literary history. Again, there were very few direct responses. I assured them I was not there to test them, there were no wrong responses; I was just curious. Next, I began building up to the narrative, setting the scene: “Let’s take a look at what was surrounding Douglass—events, people, issues in America that would affect him and his views and actions. I want to ask you a question, and you will have to guess the answer. When was the first African American newspaper published?”

Student responses included the 1970s, 1960s, 1980s, 1950s, 1930s. They were all surprised when I said 1827 and shared a primary source example. What happened next is exactly how I wanted the learning process to proceed:

Student 1: Wow! Why? Why did they publish? What did they publish?

Student 2: What was their goal?

Student 3: Who read this newspaper?

Student 4: How did they distribute it, and were there any other African American newspapers?

The increase in the students’ interest was clear. They even sat up a bit straighter and leaned in to the growing conversation.

Next, I showed them two primary sources—the first edition of Freedom’s Journal and an edition of Douglass’ Monthly. As each student viewed the documents (one they could hold in their hands, the other they could see on my iPad), I was thrilled to see that they were actually reading the texts and that their reading prompted further questions about Frederick Douglass.

I mentioned the relationship of Emerson’s essays to the unique “Americanness” of Douglass’ language and style in his Narrative. Before we realized it, the period ended, with everyone still in animated conversation—a very different response from that at the beginning of the class.

Click here to learn more about Teaching Literature In The Context of Literacy Instruction.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Jocelyn A. Chadwick has been an English teacher for over thirty years—beginning at Irving High School in Texas and later moving on to the Harvard Graduate School of Education where she was a professor for nine years and still guest lectures. Dr. Chadwick also serves as a consultant for school districts around the country and assists English departments with curricula to reflect diversity and cross-curricular content. For the past two years, she has served as a consultant for NBC News Education's Common Core Project for Parents, ParentToolkit. In June 2015, Chadwick was elected Vice President for the National Council of Teachers of English.

John Grassie is a veteran broadcast journalist, with more than 25 years’ experience producing news coverage, program series, and documentaries for Public Television, NBC News, and Discovery. During his broadcast career, Grassie’s work received numerous awards for excellence in journalism.