By Brian J. Melton

To be honest, when I started my Heinemann action research project in August 2018, I had no clue what I was doing. I had this sort of nebulous notion that our kids were leaving high school with a very poor understanding of what it is to do deep, meaningful, scholarly critical reading and writing. I knew in my heart that the answer involved creativity, but there were some real moments at the beginning of the year—and well into the start of the second semester—where I would attempt to do this work with my students, asking them to create a piece of art in response to a poem, or a short story in response to a novel chapter, and I had the feeling the kids were thinking to themselves, “Man, Mr. Melton is super weird.” I was just some dude wearing the outfit of the researcher yelling into my Twitter account. The self-doubt really crept in when Rida, one of my most skeptical research subjects, tossed her hand-drawn Macbeth comic book at me and said, “Melton . . . like, I appreciate what you’re trying to do. But I don’t think any of this creative stuff is going to help me prepare for next year.” I mean, was she right?

I started doing my own creative thinking. I was concerned, at the very core of my research question, with the connections students make between what they know and what they are reading in class. Giving the students space to develop their own creative identity was another pathway to the creation of meaning and empowerment of the student as scholar. Sometime in late February, when we began working on a Macbeth analysis essay, I rolled out eleven different prompts and students selected whichever was closest to the way they saw the play. It was limited choice, like a Denny’s menu, but it allowed a structure for the students to confront their interpretations. Initially, I was simply trying to give the students more creative choice. However, I started to see that what I had been doing was slowly building, through a variety of different creative exercises, student agency through that choice.

…

When I declared my major as English literature at the University of Texas, I quickly noticed that I had no clue how to write an academic essay. The first few papers I turned in to my professors were rightfully trashed, but the feedback was limited on how to progress as an academic writer. So, I took to the stacks at the Perry-Castañeda Library and started digging for critical analysis that aligned with what I was already curious about in the novels and poetry we were reading. I did something that I now watch my own toddlers do as they engage with the world around them: I found model texts and began to imitate those. It is certainly something we embrace at the high school level in regard to narrative, but now I encourage its use in the analyses we ask our students to do.

So when Isabella said, “Mr. Melton, writing this is so hard! Why did you give us so many prompts?” something clicked.

“What I’d really like to do for the next essay,” I said, a little off the cuff, “is to get rid of the prompt entirely.”

The look of panic in her eyes told me the idea had merit.

“I think I might die,” Isabella said.

I smiled. “Not if we do it right.”

Suddenly I had a real and achievable goal for the addition of art, poetry, and music into the ELA curriculum. I realized that what I had been trying to build through giving the students different types of interpretive experiences was their confidence as scholars. As Jean Piaget explored throughout his career, a child’s first instinct in their educational life is to begin to imitate their parents and other caregivers. When an adult waves at an infant and that infant waves back, we regard this event as a milestone in a child’s development. If a parent were to take a child’s hand and make the motion for them, no one would congratulate the baby for waving. They certainly wouldn’t give that baby an A+. However, when it comes to the practice of literary analysis, teachers often wave a student’s hand for them.

…

Students are asked to go home, passively read the material put in front of them, then wait for the teacher’s interpretation of the text during the lecture the next day. We hope they take notes, and then eagerly wait for those students to parrot the interpretation back to us either on a test or in a highly structured essay written to a prompt we have created based on our own interpretive end game. This is hardly the way it is done in the academic world. No self-respecting professor sits down in front of a computer with a stack of John Updike novels and a set of notes to simply parrot the work of Harold Bloom. If we want our students to produce quality literary analysis, we need to gradually remove the scaffolding and allow the space for them to creatively engage with the text and to, as Katherine Bomer writes in The Journey Is Everything, “closely imitate” the work of established academics. Literary analysis too can feel like “play.” We just need to shift our thinking.

Our next essay was Wuthering Heights and I decided to make Isabella’s nightmare come true: it was time to write the promptless essay. As we read through the novel, I intentionally introduced different critical interpretations into the discussion by giving the students short chunks of theory on a variety of topics—from the role of gender in Brontë’s novel to the relationship between evolution and natural theology as symbolized by the two houses. We talked about race theory, read some feminist theory, discussed the role of the triangle slave trade in Victorian England, and looked at the role orphans play in biblical stories. To focus their thinking, I asked the students to select a topic, trend, or theme that stood out to them as viable for analysis. This is where we hit a snag.

The day before, we had fallen down a rabbit hole of sorts. Following a discussion about the role orphans play in the novel, we discussed the scene in which Heathcliff hangs Isabella’s dog Fanny from a tree. After we read through the scene again, I looked out into the classroom and asked, “So guys, the question I have for you is . . . what in the world is up with all of the dogs in this novel?” The interpretations were pretty surface level, and I could tell they hadn’t given the repeated dog references much thought at all. Finally, Vidhi M., one of the most thoughtful writers in class, made the connection between Fanny’s strangulation and what would probably happen to Isabella at Wuthering Heights. After several light bulbs in the form of “oohs” and “ahhs,” I assigned the students an online discussion asking them to identify the trend/topic/theme that they would be interested in tracking for the remainder of the novel in preparation of their promptless essay.

I was excited to see what the students were interested in, so I monitored the online discussion pretty closely that evening and what I got was underwhelming. Student after student replied in the discussion thread that what they were most interested in tracking for the remainder of the novel was, you guessed it, “dogs.” My heart sank.

I returned to class the next day and addressed the issue. “Guys, do you think I would want to read thirty essays about orphans and dogs?” The kids all sheepishly laughed, but, in their defense, why wouldn’t I? All essay prompts ever ask of students is to write to one specific topic or subject, and that topic reflects exactly what we talk about in lectures and discussions. What the kids were saying on that discussion board was simply, “See Melty, we were listening in class today and we got it!” Isn’t that what we are asking of our students when we give prompts? “Were you paying attention? Did you retain the information long enough to make it to the next time I ask you about it? You did? Here’s a grade!”

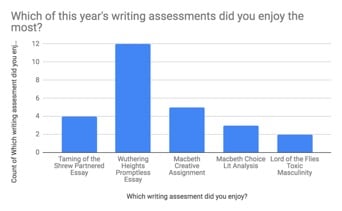

By removing the prompt for the Wuthering Heights assessment, I was challenging the students to own their interpretations of Brontë’s novel. Additionally, I forced my students (many against their will) to authentically think about what they were interested in researching and writing about. Gone was the idea that if they missed reciting a specific lecture, their essay grade would suffer. They were free to explore. In addition, I wanted students to model the writing I knew they would be doing in college, so I made scholarly research a requirement for the essay before they wrote their thesis statement. During the research phase, a majority of the students were exposed to additional critical theory that shored up the interpretations they were already making. I can think of no better way to begin to trust one’s own ability to make meaning of a text than to construct a theory and then discover that published academics have had similar ideas. It validates, and what our students need is validation of their ideas, not a recitation of ideas they’ve heard in class. As evidenced by the survey my students took at the end of the year, a majority of the class enjoyed the promptless Wuthering Heights essay more than any other essay we wrote throughout the year.

…

Was it scary for them to be so unstructured? Almost unanimously. But we had been working on freedom and creativity as part of the class since the beginning of the year. In hindsight, helping students develop their own creative voices was foundational to their ability to explore their own interpretations.

Was it scary for them to be so unstructured? Almost unanimously. But we had been working on freedom and creativity as part of the class since the beginning of the year. In hindsight, helping students develop their own creative voices was foundational to their ability to explore their own interpretations.

Ishita P. explains:

I liked the freedom we had. If you gave us that [promptless essay] at the beginning of the year I would have freaked out, but I felt like the work we did in this class led to writing this essay. I liked being able to come up with thoughts and ideas for myself and express them without too many restrictions.

Lucy N. further explained that

[The Wuthering Heights essay] was my highest grade and even though at first I felt lost, once I got to research, formulate my own thoughts and write what I wanted to write, it was nice. It felt like I was being intellectual and being rewarded for something that is normal in the world of writing, but not the world of high school writing.

As to Lucy’s discussion of her grade, it was true across the class. I believe that because students were writing less for the grade and more from their own understanding of the novel, their grades, on average, were much higher. According to the survey, even students who hated reading Wuthering Heights still found the essay about Wuthering Heights to be the most gratifying of the essays we wrote in class.

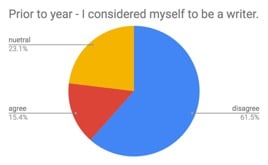

One of the most informative pieces of data to come out of the research was that the students became more confident in their overall belief in themselves as writers. As teachers, we often put far too much emphasis on the corrective nature of writing. Through standards and scaffolding we eventually squeeze the life out of the process, as evidenced by the “prior to the year” data.

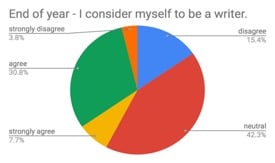

Nearly 62 percent of my sophomore students did not consider themselves to be writers and another 23 percent did not feel confident enough to say that they were. However, by the end of the year, the results were inspiring. With the exception of the one outlier, a significant percentage of students viewed themselves as writers and were more confident and agentive. If a simple shift in approach in the types of reading and writing our students are doing in class can make that much of an impact in a year, a major shift in curriculum across disciplines would have a massive impact in the way our students see themselves as scholars.

Nearly 62 percent of my sophomore students did not consider themselves to be writers and another 23 percent did not feel confident enough to say that they were. However, by the end of the year, the results were inspiring. With the exception of the one outlier, a significant percentage of students viewed themselves as writers and were more confident and agentive. If a simple shift in approach in the types of reading and writing our students are doing in class can make that much of an impact in a year, a major shift in curriculum across disciplines would have a massive impact in the way our students see themselves as scholars.

Academic writing was the furthest thing from my mind when I came up with my research question and decided to incorporate more creativity into the classroom. I knew that adding more creative components into the ELA classroom wouldn’t be detrimental to a student’s academic writing, but I did not expect the impact the creative work we did would have on the academic. In listening to my students discuss their experience this year in a recorded group chat, I walked away with the knowledge that even small shifts in crossing the creative desert can have an incredible impact on both our students and our classroom.

…

Brian J. Melton started his career in radio, journalism, and public relations. He integrates the experiences from his first career into his current role as an English and Creative Writing teacher at Glenbard North High School in Carol Stream, IL. He also advises a slam poetry team, who in 2017 performed at the Louder Than A Bomb youth competition. Brian believes in the power of conversation and self-reflection and infuses these values into his practice as an educator and leader. You can follow him on Twitter @Beezy_Melt

Brian J. Melton started his career in radio, journalism, and public relations. He integrates the experiences from his first career into his current role as an English and Creative Writing teacher at Glenbard North High School in Carol Stream, IL. He also advises a slam poetry team, who in 2017 performed at the Louder Than A Bomb youth competition. Brian believes in the power of conversation and self-reflection and infuses these values into his practice as an educator and leader. You can follow him on Twitter @Beezy_Melt