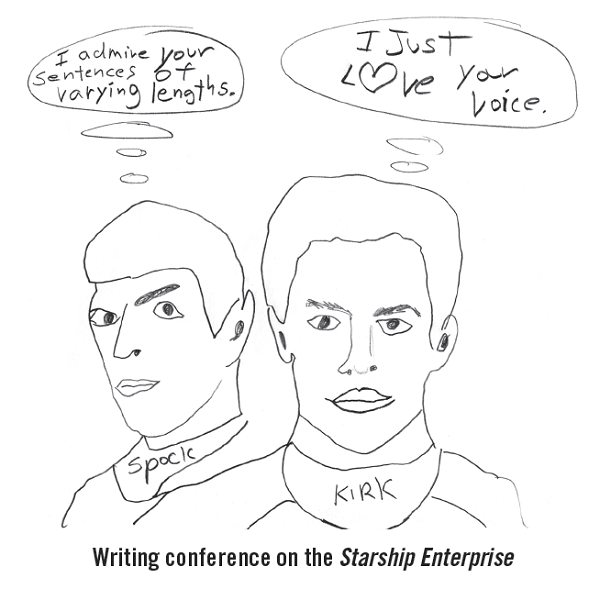

Barry Lane's best-selling After THE END helped teachers see revision in a whole new light and inspired a generation of students to not only embrace revision but to realize that writing is revision. Now, the long-awaited second edition keeps Barry's humorous and endearing tone while updating his ideas and lessons for teaching writing with heart. In today's post and video adapted from the book, Barry compares students' relationship with academic writing to that of Kirk and Spock, commanding officers of the U.S.S. Enterprise.

More Kirk, Less Spock

by Barry Lane

[dropcap]One[/dropcap] of the great longstanding offenses of boring academic writing instruction is the insistence that good writing begin with a predictable central idea to prove, rather than a question to explore and expand upon. One glance at writing rubrics from any state or testing company will find the phrase controlling idea mentioned throughout. Terms like this are never used by writers, who spend more time chasing ideas than controlling them. Good nonfiction writing, according to most states and test companies, is viewed as a sort of mathematical equation: Controlling idea (thesis) + Supporting relevant evidence + Conclusion = Excellent essay.

I call this Spock writing, after the half-Vulcan, half-human character played by the late Leonard Nimoy on the famous TV series Star Trek. Like most Vulcans, Spock is supremely rational and calculates each situation with his overworked left hemisphere. Spock would simply be a robot if not for his half-human lineage and his close association with Captain James Tiberius Kirk, the dreamy, defiant, unorthodox, deeply flawed leader, who is just as likely to punch his way out of a situation as calmly negotiate. The problem with state standards and other rigid textbook approaches to writing is that they are all Spock and no Kirk. All reason and no bluster. The best nonfiction writing has an element of Captain Kirk in it. It is unpredictable, surprising, dreamy, inquiring. It contains, in Star Trek language, strange anomalies. Not all paragraphs begin with topic sentences. Not all details are held in place by a neat controlling idea. The inquiring writer takes the reader on a journey, and neither is totally certain where they will end up. The writing is organized around the passion of the author, a question trying to be answered, an idea unfolding, a thesis explored, not just proven.

Once, I was asked to write a short essay on the power of reading. I began writing with no idea where it would lead. When I started thinking about reading, I started by comparing my TV days of childhood when I didn’t read with the days after I started reading. I remembered some key reading experiences. By the end of the essay, my writing led me to one very simple truth: reading is not a skill; it is a miracle. I found the main idea of my essay in the very last sentence. Imagine how the essay would have read differently if I had started with, “Reading is not a skill; it is a miracle. There are three main reasons why. First of all…” Encourage your students to take the journey to the thesis, or, to paraphrase the famous captain, to boldly go where no nonfiction writer has gone before.

After THE END, Second Edition: Teaching and Learning Creative Revision is available now.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Barry Lane has taught writing in grades K–12, and authored many professional books to help teachers teach writing with joy and passion. His other books include Reviser's Toolbox, But How Do You Teach Writing? and Force Field for Good (with Colleen Mestdagh).

Barry Lane has taught writing in grades K–12, and authored many professional books to help teachers teach writing with joy and passion. His other books include Reviser's Toolbox, But How Do You Teach Writing? and Force Field for Good (with Colleen Mestdagh).