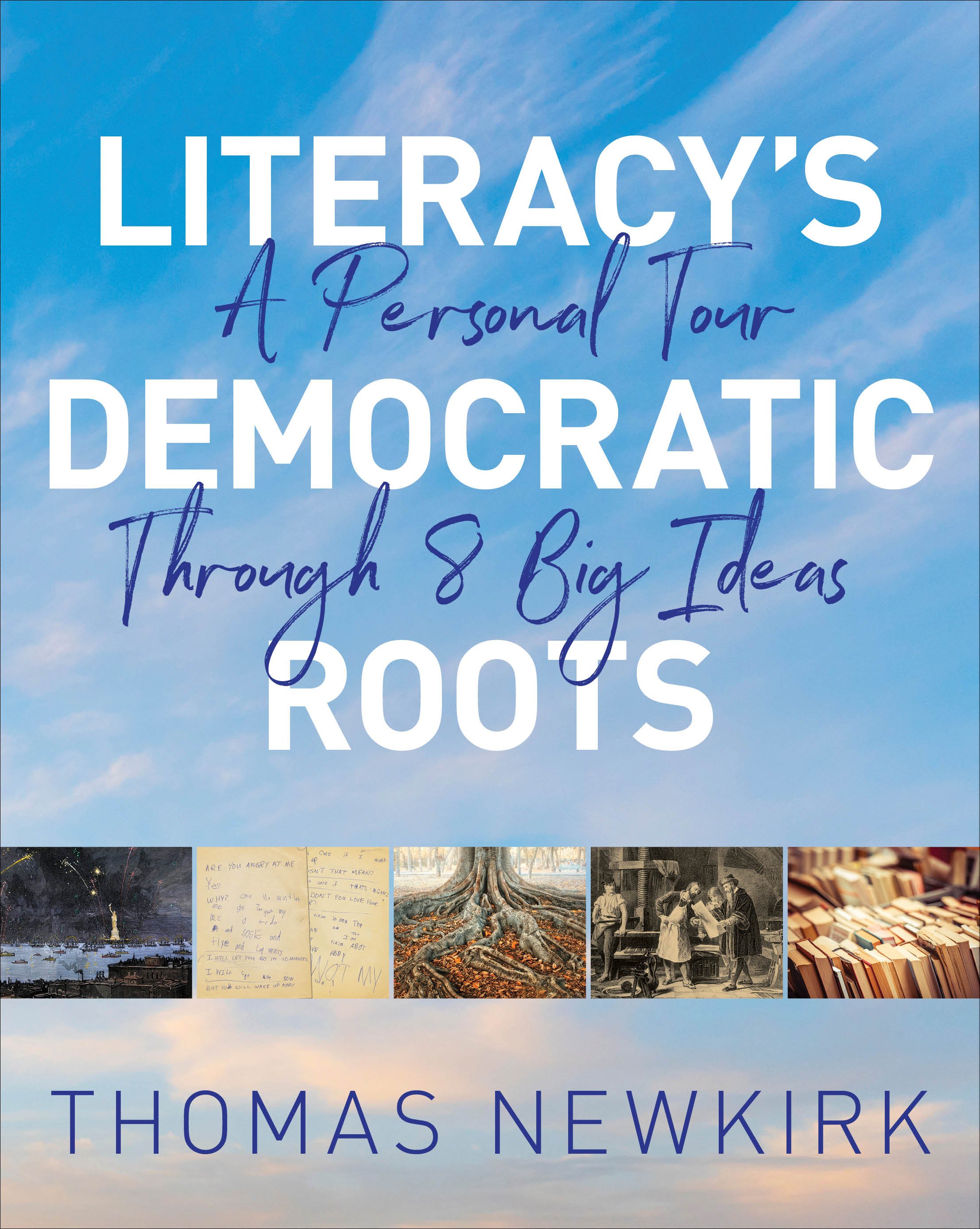

The following is adapted from Literacy’s Democratic Roots: A Personal Tour Through 8 Big Ideas by Thomas Newkirk.

Literacy and Democracy—or “Where I’m From”

If you enter almost any public school, you will encounter a range of offices, for administrators, counselors, nurses, custodians, security. But there will be one type of office you will not find—an admissions office, for the simple reason that public schools are open to all. Don’t speak English? You’re in. Need a wheelchair to move from place to place? You’re in. You’ve suffered from trauma or have a learning disability? You’re in. You’re a Democrat, a Republican, a Free Stater? Christian, Muslim, agnostic? You’re in.

This absence of an admissions office, this open door, is the extraordinary feature of the public school. Its absence symbolizes a promise, or at least an aspiration, to serve the needs of all who enter, to make everyone feel welcome, respected, at home, and successful. That we so often fall short of this ideal does not negate its significance.

The public school, what Horace Mann called the “common school,” open to all, is a great democratic ambition, achievement, and challenge. It was a realization of that wonderful expression of John Adams, prominent in the Massachusetts Constitution (and the New Hampshire Constitution, which copied it), commanding that “in all future periods” governments should “cherish” public education (Volinsky 2004, 837). Cherish, hold dear.

When I first played with the idea of writing about big generative ideas, I considered each chapter a separate unit, unconnected thematically. But when I explained the project to others, the question was always “So how are these tied together?” At first, I resisted this expectation. It felt like I was planning a basic dive—say, a one and a half flip—and someone was asking that I add a full twist. But I became convinced there was a thematic connection—to democracy. Hence the current title.

If someone with way too much time on their hands were to do a word search of all I have written, I suspect democracy would not appear. It seemed that democracy, or patriotism, or love of country, was always co-opted by the educational right, who cling to test scores (especially when they show decline), “cultural literacy,” (white) nationalism, or a sanitized view of our history, and who at some level see diversity as a problem. Whatever the question, the answer was often testing, standardization, or privatization.

A case in point: In 1983, A Nation at Risk warned us (melo)dramatically that public education was so deficient that “the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threaten our very future as a Nation and a people” (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 6). Or worse. “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war” (6).

Only one problem—even as the ink was drying from that report, the United States was entering a prolonged period of extraordinary growth, running to about the year 2000, averaging 3.5 percent growth over that period (Macrotrends 2010–23), outpacing the Japanese economy, which was the concern at the time. Clearly US workers, educated in US schools, had something to do with that. Talk about bad predictions. Yet I’m not aware of any retractions or corrections—because only negative national education stories sell.

It has also felt to me presumptuous to justify or explain my ideas in such broad political terms. My focus was usually on the individual student, held back by the constraints of curricula. The title of my last book, Writing Unbound, surely emphasized that theme. But as I thought about what the eight ideas in this book have in common, I did feel that there were democratic values at the heart—that they all had to do with access and diversity, with finding ways of connecting educational goals with the funds of knowledge students bring in when they walk through that door.

As I was refining my idea of this book, I sent out a tweet that received a strong response—with some followers turning it into a visual. I wrote: “The house of literacy has a thousand doors. Our job is to help students find one that will let them in.” It seemed to me there was the germ of a political idea here—that too many students never entered the house of literacy, and why was that? And what could we do about it? How can we make entry more possible, more inviting, more pleasurable? How are we as educators being held back by rigid ideas and curricula that do not reflect and honor what students, particularly students of color, students outside the mainstream, bring to schooling? How can we disrupt those patterns? How can we tell a better story about literacy? I found that these questions guided me to the ideas I would write about—and that it no longer seemed presumptuous to see this as a democratic issue.

As I wrote Literacy’s Democratic Roots, I came to see myself as a tour guide, taking you and other readers through eight big, amazing houses—each with more rooms than we could get to. I have spent time in the rooms of these houses. I’ve lived in them, and I know others who have helped build and furnish them, even some who set down the foundations. We’ll hear from some of them. I will call attention to artifacts in these rooms and tell stories. I’ll have to leave out a lot since our time is limited, and almost anyone who has written on literacy in the past thirty years has spent time in these houses or added their personal contribution, even done some of the major (re)construction.

In preparation for writing, I asked a number of scholars what their eight great ideas would be. Many of their suggestions would have made for possible chapters—scaffolding, writing across the curriculum, zone of proximal development, prior knowledge, comprehension strategies, voice, choice, flow, approximation, and metacognition, to name a few. Some of my correspondents tactfully pointed out that the idea of idea was vague and that it might include practices, concepts, or fully developed theories. One might protest that independent reading is a practice while Rosenblatt’s transactional model of reading is a fully developed theory. To this imprecision, I can only plead guilty.

As I challenged myself to think of a unifying principle for Literacy’s Democratic Roots, it came down to a core belief that as humans we have the great gift, the great evolutionary achievement, of speech and story. It’s what we do best—and all literacy instruction needs to honor and build on that gift. It is sinful to make students feel inadequate or out of place—to silence them, to treat them as empty vessels, or to make literacy such a chore that they choose not to try. Sinful. The traditions of writing instruction in particular—their obsession with form and correctness—need to be corrected. These eight big democratic ideas can help us build a house that everyone can enter.

Thomas Newkirk is the bestselling author of Minds Made for Stories, along with numerous other Heinemann titles, including Writing Unbound; Embarrassment; The Art of Slow Reading; The Performance of Self in Student Writing (winner of the NCTE’s David H. Russell Award); and Misreading Masculinity. He taught writing at the University of New Hampshire for thirty-nine years, and founded the New Hampshire Literacy Institutes, a summer program for teachers. In addition to working as a teacher, writer, and editor, he has served as the chair of his local school board for seven years.