The following is an adapted excerpt from Valerie Bang-Jensen’s Literacy Moves Outdoors.

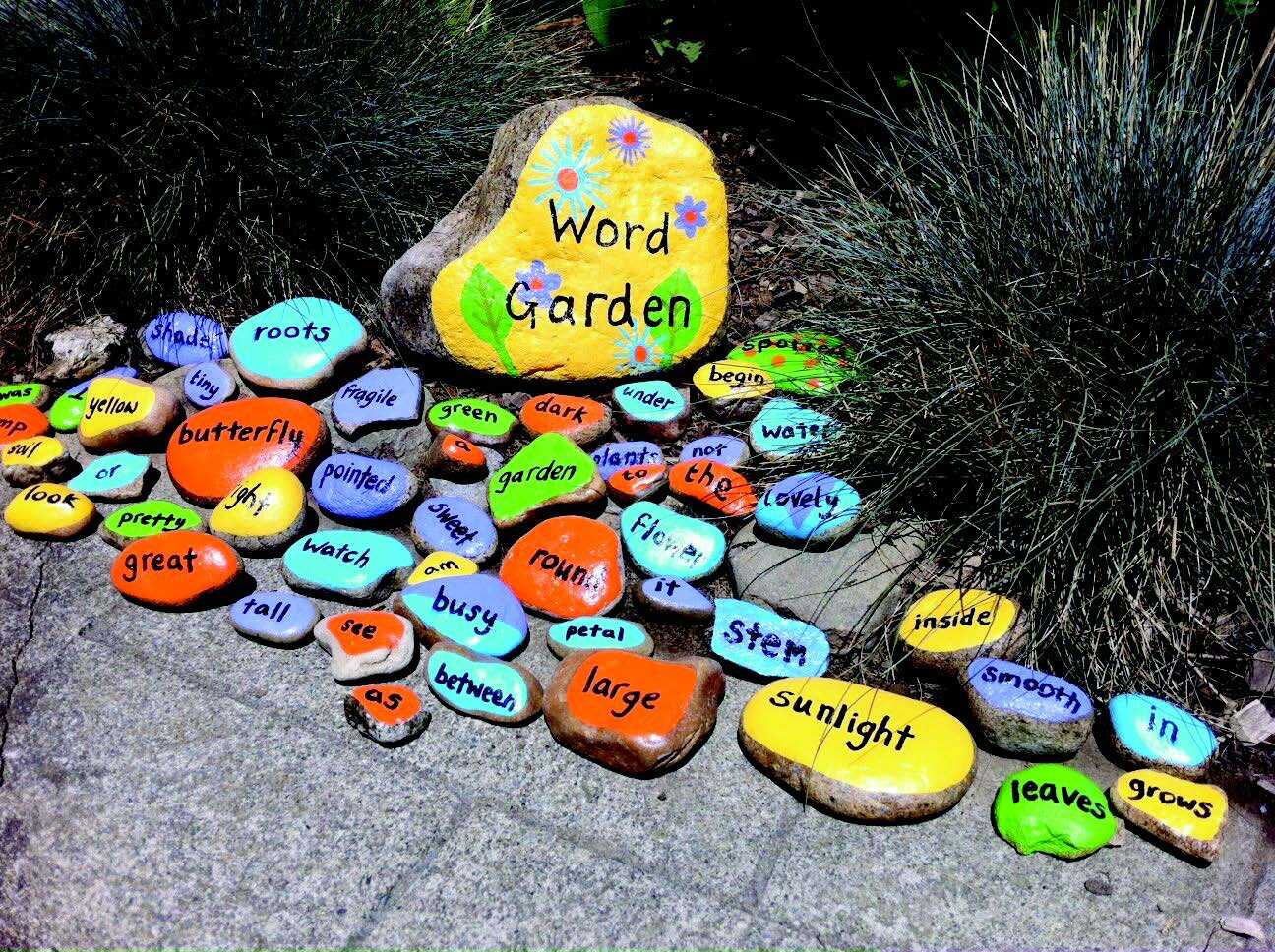

If you’ve played around with magnetic poetry, then you’ve already got the idea of a word garden. Imagine the words on stones, blocks of scrap wood, painted jar lids, or other materials placed in a corner of your playground, a bed of gravel, or any available space. The words might be painted, etched, or written on the stones with chalk or a marker—the result provides many options for wordplay and learning. Like magnetic poetry, students enjoy moving these words around, but word gardens invite participation far beyond the physical task. Your students can leave messages, create poetry, start a discussion, make a joke, and just about everything else you can do with words.

Word work in the garden

A word garden, because it is made up of words, can be the perfect place for word study and wordplay. Much of the word work you do in your classroom can take place in a word garden, along with the added benefits of being outdoors and the chance for students to move around. Once you and your grade-level team have created the stones with words from your phonics or word study curriculum, word sorts like patterns, syllables, and concepts can be done with stones.

A word garden, because it is made up of words, can be the perfect place for word study and wordplay. Much of the word work you do in your classroom can take place in a word garden, along with the added benefits of being outdoors and the chance for students to move around. Once you and your grade-level team have created the stones with words from your phonics or word study curriculum, word sorts like patterns, syllables, and concepts can be done with stones.

Poetry

Word gardens are a perfect match for poetry writing. If you are writing words with chalk or paint, then your poets can expand the selection of words by adding words they choose as they write their poems. A different type of writing challenge can be to craft images and lines only from words that are right there in front of you. You might prompt students to see the possibilities in the word stones: Where might the words gnome, poncho, or rumble lead your mind? Is there a “found” line already set up in stones that you find inspiring? What might you add to it to make it your own? Teachers often encourage students to create poems individually, in pairs, or in small groups, because partner work invites conversations about language.

Word gardens are a perfect match for poetry writing. If you are writing words with chalk or paint, then your poets can expand the selection of words by adding words they choose as they write their poems. A different type of writing challenge can be to craft images and lines only from words that are right there in front of you. You might prompt students to see the possibilities in the word stones: Where might the words gnome, poncho, or rumble lead your mind? Is there a “found” line already set up in stones that you find inspiring? What might you add to it to make it your own? Teachers often encourage students to create poems individually, in pairs, or in small groups, because partner work invites conversations about language.

Comprehension

Word stones are great tools for working on comprehension, too. A second-grade teacher helps each of her students create a set of three word stones labeled B, M, and E, to represent Beginning, Middle, and End. During and after read-alouds she engages the children in discussion, using the stones as prompts in identifying different parts of the story. She also challenges them to retell stories using word stones that say main idea and supporting detail.

Word stones are great tools for working on comprehension, too. A second-grade teacher helps each of her students create a set of three word stones labeled B, M, and E, to represent Beginning, Middle, and End. During and after read-alouds she engages the children in discussion, using the stones as prompts in identifying different parts of the story. She also challenges them to retell stories using word stones that say main idea and supporting detail.

Make science connections in the word garden

One city school in Vermont placed a word garden in a corner of the play yard next to raised garden beds to create inspiration for science notebook writing. The science coach selected the words she wanted students to use as a springboard for observations: data, observe, seeds, and hypothesis are found among other more common and versatile high-frequency words to support student thinking and writing. Students chalked additional words onto stones as they wrote about their observations. Because the word stones were outside near the raised beds, they served as a word wall for brainstorming science notebook writing.

One city school in Vermont placed a word garden in a corner of the play yard next to raised garden beds to create inspiration for science notebook writing. The science coach selected the words she wanted students to use as a springboard for observations: data, observe, seeds, and hypothesis are found among other more common and versatile high-frequency words to support student thinking and writing. Students chalked additional words onto stones as they wrote about their observations. Because the word stones were outside near the raised beds, they served as a word wall for brainstorming science notebook writing.

Social studies in the word garden

Any social studies topic can be explored using a word garden, whether the curriculum is prescribed or emergent. A history-based curriculum might inspire a garden featuring events, concepts, and vocabulary that invites students to match up the ideas represented by words on stones.

Any social studies topic can be explored using a word garden, whether the curriculum is prescribed or emergent. A history-based curriculum might inspire a garden featuring events, concepts, and vocabulary that invites students to match up the ideas represented by words on stones.

A common social studies unit for early elementary grades is community, with a focus on important institutions in a city or town, the services provided, and the roles that people play. Together with your students, you might add stones to your garden identifying these three groups and related vocabulary words. Stable large stones for the institutions and smaller ones for the services and roles would enable students to physically match the ideas and concepts. With chalk or paint, they could add new ones as the unit progresses.

Other Connections: Guidance

At one elementary school, a guidance counselor’s purpose for the word garden is a “Zen space for children.” Her goal is to create a place for students to get outside and connect with nature in a meaningful way. Discussions with fifth graders end with each student contributing a word that has the potential to spark an idea when others read it. The fifth graders’ brainstorm list generated words such as chill, Zen, family, peaceful, and nature. These word choices offer the counselor and students a chance to launch a discussion that goes well beyond the confines of a garden, such as considering the question “What does peace mean to you?”

At one elementary school, a guidance counselor’s purpose for the word garden is a “Zen space for children.” Her goal is to create a place for students to get outside and connect with nature in a meaningful way. Discussions with fifth graders end with each student contributing a word that has the potential to spark an idea when others read it. The fifth graders’ brainstorm list generated words such as chill, Zen, family, peaceful, and nature. These word choices offer the counselor and students a chance to launch a discussion that goes well beyond the confines of a garden, such as considering the question “What does peace mean to you?”

While there are many ways to use a word garden in literacy learning, perhaps some of the most surprising and strongest arguments are about building a sense of school community and moving beyond age or grade-level curricula because all students can contribute in various ways. Word gardens are engaging and adaptable learning spaces that are easily created and allow teachers to structure experiences that help students meet curricular goals.

Literacy Moves Outdoors provides the rationale, resources, and information to help you get started, all organized to help maximize learning and connect what you do outside to what you teach inside. Explore and adopt practices that engage students, meet their interests and needs, and give them the tools to communicate and discover themselves and the world around them.

Also available as an audiobook! Listen to a sample on the Heinemann commuter podcast.

Valerie Bang-Jensen is Professor of Education at Saint Michael's College, where she has earned the college’s Rathgeb Teaching Award. She received her A.B. at Smith College and MA, M.Ed., and Ed.D. degrees from Teachers College, Columbia University. Valerie has taught in K-6 classrooms and library programs in public and independent schools in the U.S. and Paris, and was the district elementary writing coordinator in Ithaca, New York. She serves as a consultant for museums, libraries, schools and gardens for children. Valerie's areas of interest include children's literature, nonfiction, and connections between literacy and first-hand experiences. Valerie co-founded the Teaching Gardens of Saint Michael’s College, including one called Books in Bloom, which features flowers found in children’s books.