The conversation about graphic novels and comics as a valid form of literature has been going on for decades at this point. For me, this debate has been settled. Comics ARE a valid and beneficial form of reading. If you need further reading for colleagues or parents check out these resources:

The conversation about graphic novels and comics as a valid form of literature has been going on for decades at this point. For me, this debate has been settled. Comics ARE a valid and beneficial form of reading. If you need further reading for colleagues or parents check out these resources:

- Why Comics?

- Don’t be afraid to let children read graphic novels. They’re real books.

- Reading Graphically: Examining the Effect of Graphic Novels on the Reading Comprehension of High School Students

- Visual Language Lab: Comics in Education

- Comics in the Classroom: Why Comics?

After the recent webinar, I received a query asking for resources to help convince others who might ask, Why should we teach students to WRITE graphic novels? This is a question that has not been as widely discussed. I will offer three reasons why teaching students to compose graphically is beneficial. I will focus on composing narrative graphic novels, as this is the focus of our Unit of Study.

Strengthening Story Structure

When we teach children to plan their prose stories, we teach them to plan a logical sequence of events. Perhaps a timeline or a story arc is used to support students in this work. Students need this skill when writing graphic narratives as well.

A prose writer, a writer who writes in sentences and paragraphs, does not need to worry about which events are happening on which page of their book. A big reveal on the right-hand page of a prose novel, will not be spoiled by a page turn. In graphic storytelling, it matters which events occur on which pages.

For example, if a story is about a girl searching for her lost dog, the moment when she finally discovers that her dog had been sleeping in her bed the entire time is a big reveal. In a prose novel, this reveal could happen on an odd numbered, right-hand page. In a graphic novel, it shouldn’t. As soon as a reader turns the page in a graphic novel, they will see the dog sleeping in her bed on the odd-numbered page and all tension is lost for the even-numbered page on the left. However, by placing this reveal moment on an even-numbered, left-hand page in a graphic novel, the tension in the previous pages is maintained and the reveal occurs after the page turn.

Whether the writer is creating a picture book or graphic novel, a writer composing graphically must consider the “page turn.” Picture book and graphic novelists might use a script or a bookmap to plan the pages on which each event occurs.  When composing graphically, stories must be planned more deliberately than in prose narratives. Scott McCloud, a comics theorist and author of Understanding Comics, would call this “choice of moment.” This means deciding which moments to show to tell your story. For me, this also means deciding which moment to leave out or leave to the reader to infer. Some events are left “in the gutter.” The gutter is the typically white space between panels. A panel represents a moment in time. In between each panel, in the gutter, time passes. These moments are left to the reader to infer and visualize.

When composing graphically, stories must be planned more deliberately than in prose narratives. Scott McCloud, a comics theorist and author of Understanding Comics, would call this “choice of moment.” This means deciding which moments to show to tell your story. For me, this also means deciding which moment to leave out or leave to the reader to infer. Some events are left “in the gutter.” The gutter is the typically white space between panels. A panel represents a moment in time. In between each panel, in the gutter, time passes. These moments are left to the reader to infer and visualize. Through planning a graphic narrative, writers must constantly consider pacing, make decisions about the moments necessary to clearly tell their story, and plan for page-turns. Asking young writers to wrestle with these decisions can be challenging, but at the same time the visual nature of the comics medium supports young writers in growing their understanding of these concepts.

Through planning a graphic narrative, writers must constantly consider pacing, make decisions about the moments necessary to clearly tell their story, and plan for page-turns. Asking young writers to wrestle with these decisions can be challenging, but at the same time the visual nature of the comics medium supports young writers in growing their understanding of these concepts.

Imagine coming back to narrative prose writing with writers who have a stronger grasp on pacing. Young writers who can visualize the events in their prose stories and decide the events that should be summarized, skipped over entirely, or “left in the gutter.” Young writers can choose the moments that should be told in more detail because they are important. Young writers who, like Dav Pilkey and Renée Russell, could begin crafting hybrid texts, one of the most popular formats with young readers today.

This work will not only transfer back to prose narratives, it could plant the seeds of future success in other media. Cinematographers, directors, cartoonists, animators, picture book authors and illustrators use the skills that writing graphic novels allows students to practice. You may be helping create the next Jordan Peele or Dion Beebe!

Creating A Pathway to Success

A lot has been written about how graphic novels support English Language Learners in comprehension and learning vocabulary, here is one example of research on this topic. Based on my anecdotal experience, it is also true that composing graphically provides access to the writing process for a wide-variety of writers.

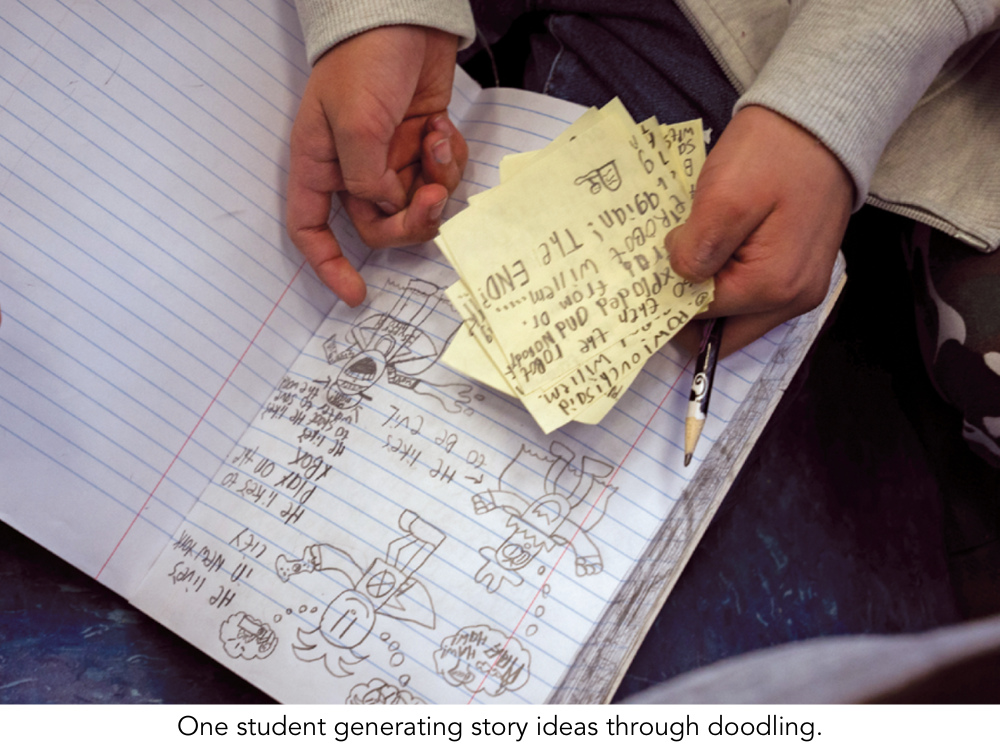

One day at New Bridges Elementary in Brooklyn, NY–a special school that centers the child in all things–I was piloting a very early version of one of the generating lessons that became session 2 in Hareem’s and my unit. This session, “Doodling to Generate Story Ideas”, teaches writers that graphic novelists often generate story ideas by doodling characters. As the young writers doodled talking pickles, big brothers, and star athletes, I coached them to sketch or jot the story ideas that came to them around their doodles.  “What does your character love? Hate?”

“What does your character love? Hate?”

“What do they want?”

“What’s getting in their way?”

“Who else in this story”

I wish you could have been in this classroom as it buzzed with the excitement of creation. As we were wrapping up writing workshop, Ms. Britt, the teacher, brought me over to one of her young writers.

“This is the most writing Amir has ever produced in a writing workshop!” she shared, holding up a page full of character sketches and the seeds of a plot. This young writer was in the process of learning English. By teaching him to begin composing a narrative through a combination of words and images, he was able to be more productive, and more importantly, more successful while writing.

This anecdote illustrates what I have seen in and heard from classrooms all over the country:

Emergent bilingual students have great success when composing graphically.

Those students who usually dread writing workshop, can’t wait to write their graphic novels.

Students who typically don’t achieve highly in writing, become the leaders and mentors to other writers during this unit.

When we only provide one pathway to success in writing, we leave a wide swath of writers behind. When we provide a variety of pathways to success, we provide multiple opportunities for our young writers to shine. Teaching kids to write graphic novels is one of these pathways.

Generating Excitement

I have been in a lot of classrooms. I have launched a lot of writing units. There is only one unit that elicits cheers from the class and it is this unit of study. When you launch this unit, you might say,

“Writers, I’ve been noticing that many of you have been doodling. You’ve been doodling in your notebooks, in the margins of your papers, basically anywhere you can. Can I tell you something that may surprise you? I have actually been admiring your doodles! Such creativity!

This has given me an idea for our next writing unit. For the next several weeks, we’re going to learn how to write…graphic novels!”

Cheers. Applause. Shared glances of disbelief. Young writers WANT to do this work. If I can teach my students something they want to learn and it will benefit their writing abilities, then I’m all in. I hope you are too.

You will never see engagement so high as during this unit. That makes this a perfect unit to bring life back to your writing workshop mid-year or to infuse energy into your class as you all limp towards the end of the school year.

So, why should we teach students to write graphic novels?

Their grasp of pacing and story structure will grow.

This unit will make students who may not see themselves as “writers” successful in writing.

They want to.

Graphic Novels, Grades 4-6, with Trade Pack by Hareem A Khan and Eric Hand

Eric Hand is a former staff developer at the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project who has taken all his expertise back into the classroom. He has a master’s degree in literacy education and has taught in a variety of classroom settings. While at TCRWP, Eric joined Hareem, Mary Ehrenworth, and others in spearheading efforts to incorporate graphic novels and comic books into Units of Study in Writing. The institute that he and Hareem co-led helped to generate enthusiasm for this important work. Currently, Eric is putting all he knows into action—and he’s learning from his students every day. He regularly posts his learning on his blog, Written by Hand. If you are looking for Eric, check your local comic book shop.

Eric Hand is a former staff developer at the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project who has taken all his expertise back into the classroom. He has a master’s degree in literacy education and has taught in a variety of classroom settings. While at TCRWP, Eric joined Hareem, Mary Ehrenworth, and others in spearheading efforts to incorporate graphic novels and comic books into Units of Study in Writing. The institute that he and Hareem co-led helped to generate enthusiasm for this important work. Currently, Eric is putting all he knows into action—and he’s learning from his students every day. He regularly posts his learning on his blog, Written by Hand. If you are looking for Eric, check your local comic book shop.