“I try to be as honest about what I see and to speak rather than be silent, especially if it means I can save lives, or serve humanity.” --Sandra Cisneros

This summer, as I was trying to regain energy and take time for much needed self-care, I heard and read reports about a state law that policed “culturally relevant” curriculum taught in schools. Former leaders of Arizona public schools moved to maintain the bill formerly known as HB 2281, which dismantled courses that offered curriculum centered on ethnic studies. Courses regarding Mexican-American history were significantly impacted. The HB 2281 bill stated:

...pupils should be taught to treat and value each other as individuals and not be taught to resent or hate other races or classes of people. A school district or charter school in the state shall not include in its program of instruction any courses or classes that:

- Promote the overthrow of the United States Government

- Promote the resentment toward a race or class of people

- Are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group

- Advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.

Why was there a movement to push out ethnic studies in Arizona schools? Who thought that these courses were angled to “overthrow”, teach “resentment”, and cast negativity on “ethnic solidarity”?

Sadness grew to rage as I looked at the children in my family who live in Arizona and wondered, whose histories will they learn? Will they even have a chance to access various perspectives, including their own? Will they be able freely and safely develop a critical consciousness? Would they have space to share their world? These questions apply not just to my own family, but to all of the students in our schools. If this bill is passed, it could be an open door for other districts around the United States to ban culturally relevant coursework. What that law doesn’t take into account is the power students feel when they are a part of the curriculum. When we teach students there is value in who they are and what they know, it becomes a launching point for learning. It helps them consider other perspectives, develop empathy, build resilience and take action.

Consider the words of critical theorist, Donaldo Macedo:

"If students are not able to transform their lived experiences into knowledge and to use the already acquired knowledge as a process to unveil new knowledge, they will never be able to participate rigorously in a dialogue as a process of learning and knowing." (19)

We can fuel student learning when we provide a safe space for students to share their histories and lives. Along with our colleagues, we can take concrete steps to begin to break down the barriers that silence students. We should begin through reflection of our practice, questioning the content of our resources and re-examining the classroom environment.

Reflecting on Our Practice

As we plan units and instruction, it’s critical to slow down and question the choices we make. Cornel Pewewardy, Native American educator, provides insight into one reason students might face adversity throughout their school experience “educators traditionally have attempted to insert culture into education, instead of inserting education into culture” (Ladson-Billings, 1995). One way we can start to insert education into culture is to reflect on what we teach, how we teach and how we evaluate.

| What I teach |

|

| How I teach |

|

| How I evaluate |

|

In my practice, I have noticed that taking a reflective stance provides students with more choice, I am more aware of possible triggers for my students, and it helps me establish a classroom culture that values different ways of knowing and understanding. One of the most important shifts has been an increased self awareness as a teacher. When I am more aware of what I teach, how I teach and how I evaluate, it helps me create an authentic, inclusive and responsive classroom environment.

Questioning the Content of Our Resources

Teachers are sometimes required to use specific materials or resources, but we do have a responsibility and a choice in how we think about those materials. We can start by asking ourselves some questions.

|

As we reflect on our resources, we might find areas of concern as I did years ago in my NYC classroom. I was planning to use a text about 9/11 with my students, some of whom were Muslim. Upon review, I noticed that the text only mentioned, “extreme Islam” and failed to provide further background information about Islam and its cultural components. I decided not to use the book because of the one sided portrayal of Islam and the assumptions it made about Muslims.

As teachers, we must search out, collect, and utilize resources that are inclusive of our students and represent groups of people in a multi-dimensional way.

Re-examine the environment

Classrooms are set up with a particular vibe in mind. Teachers spend hours designing environments that are “student friendly” and geared to “nurture.” However, environments go beyond the theme, color coordination, and learning nooks. The environment is the visual platform for what is privileged in the classroom. That visual platform of privilege can silence students and leave them feeling powerless. Throughout the school year we can always keep the visual platform in mind by thinking about:

| Texts |

Student Work and Other Displays |

|

|

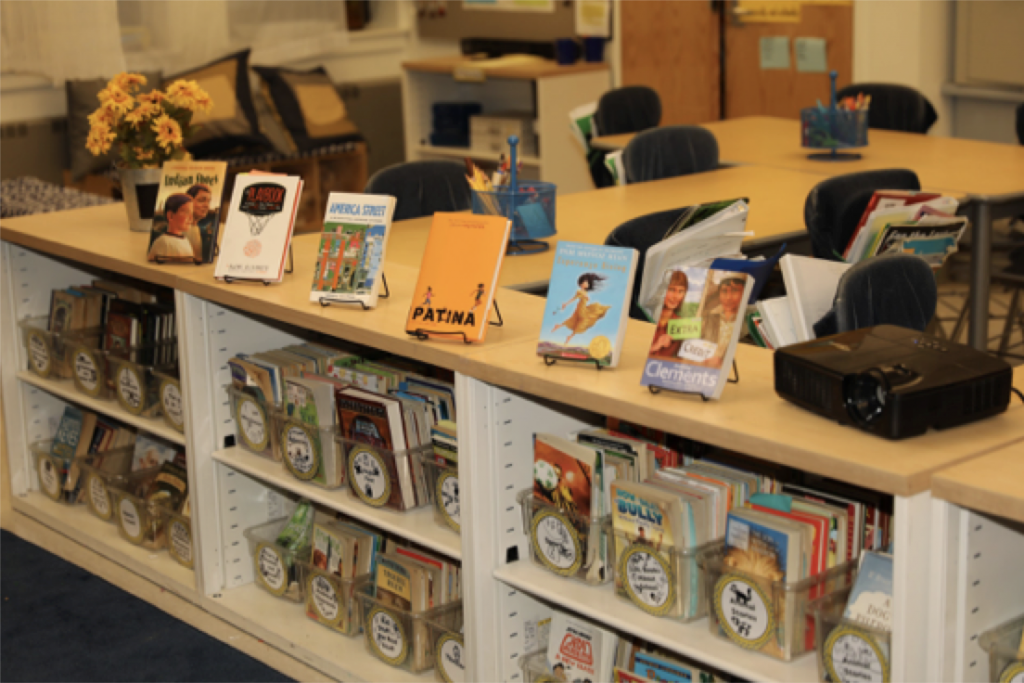

In my classroom, students contribute to the classroom environment. My students expressed the need to see more books displayed about people who shared similar experiences, who looked like them, and for voices that were missing from typical classroom libraries. As a community we chose to display texts that represented diverse identities.

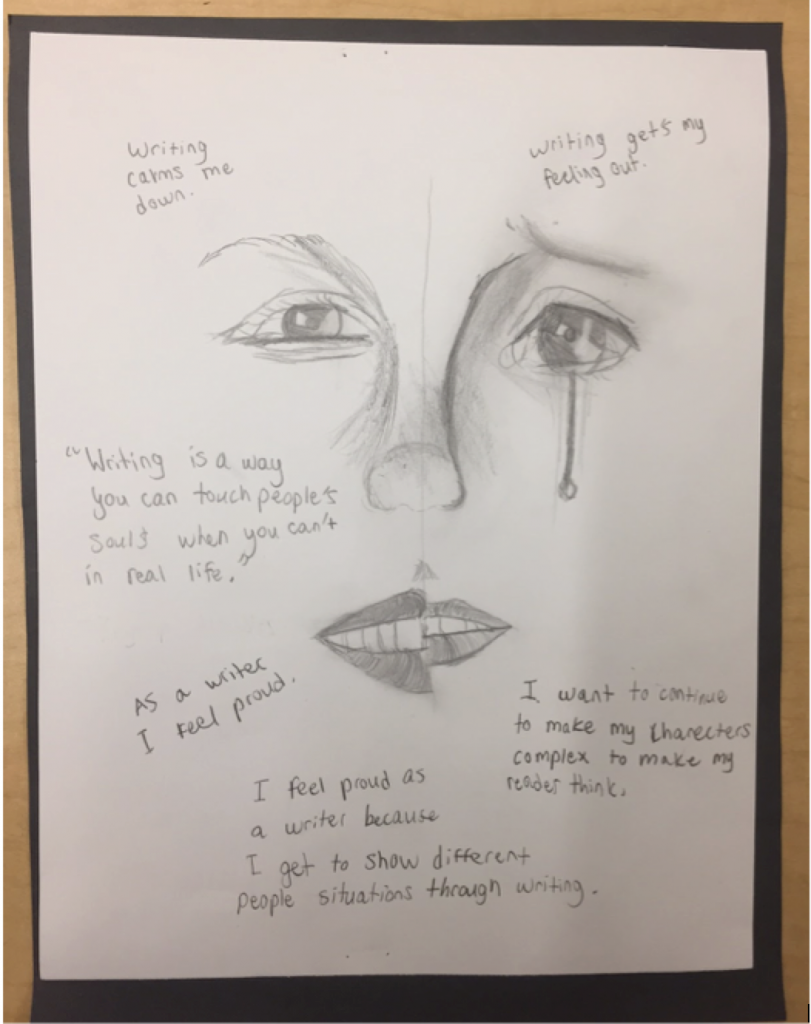

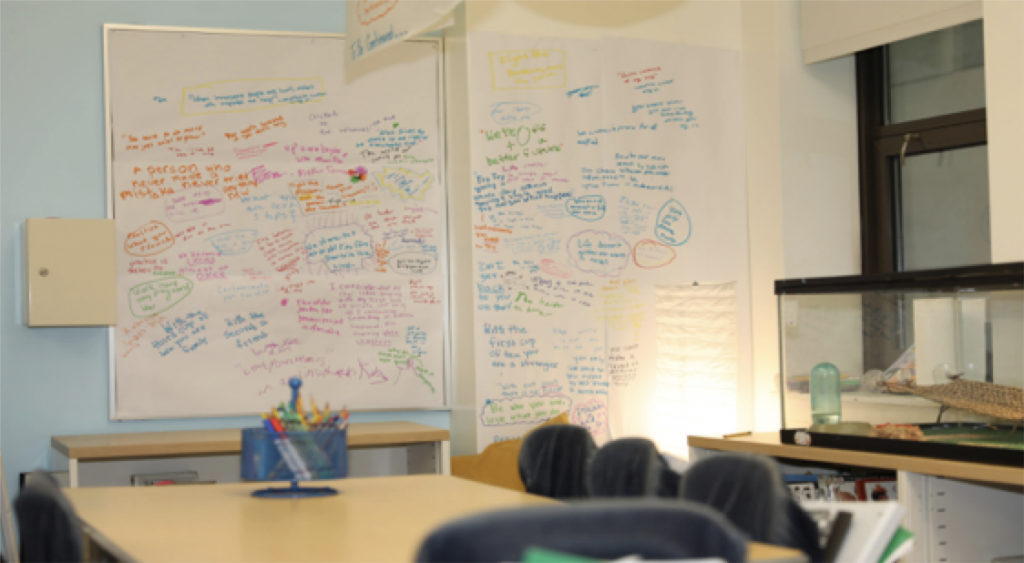

Listening to student preference is one way we can support students as they create their own environments. One student said she would feel more comfortable discussing and exchanging ideas with her peers through writing. We decided to start a thinking wall as a shared platform for all students to express their ideas.

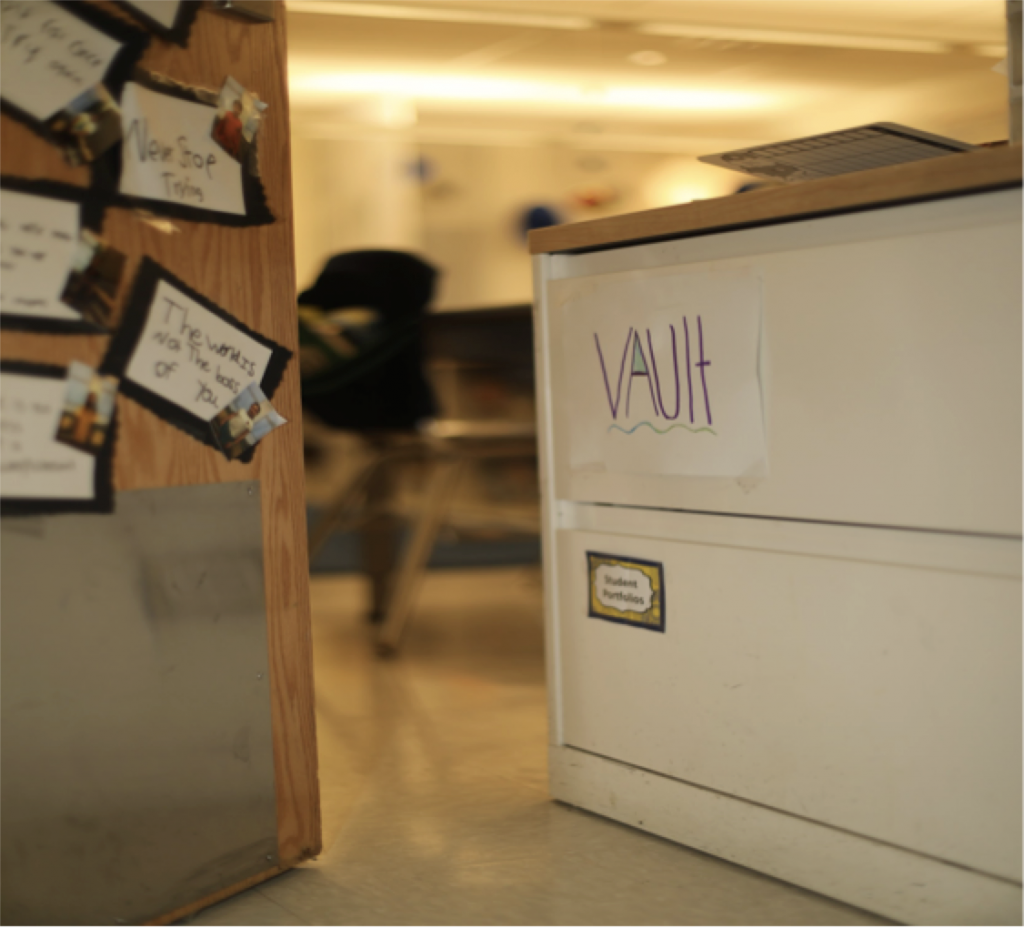

Another student expressed that he did not want his published writing displayed. He said, “I will write. I want to write, but I don’t want this up on the walls. I want this locked away.” From that day, we have had a classroom vault. This is a place where students can keep their work private.

When students take part in creating their classroom, they are empowered to make and revise their own visual platforms so that teaching and learning is truly centered on the student.

We have a journey ahead of us. One step at a time. In August, Arizona’s former bill HB 2281 was found to be unconstitutional by a U.S. District judge. We can either sit back while we allow policy makers to police our curriculum or we can fight for what we know our students and families need - to be heard and seen, to be a part of the curriculum. Let’s work to be the advocates our children need us to be.

♦ ♦ ♦

Further Resources:

- We Need Diverse Books - http://weneeddiversebooks.org/

- American Indians in Children’s Literature https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/

- De Colores: The Raza Experience in Books for Children- http://decoloresreviews.blogspot.com/

- Harvard Educational Review: Expanding Hip-hop Based Education Across the Curriculum- http://hepg.org/her-home/issues/harvard-educational-review-volume-84-number-1/herbooknote/schooling-hip-hop

- The Journey Project- http://thejourneyproject.us/

- Raising Race Conscious Children- http://www.raceconscious.org/

- Debbie Reese is a Native American researcher and teacher. You can follow her on Twitter at @debreese

- Discussion group dedicated to diverse identities in texts. This group can be found on Twitter #ownvoices

-

For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood... and the Rest of Y'all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education by Christopher Emdin

-

Upstanders: How to Engage Middle School Hearts and Minds with Inquiry by Harvey "Smokey" Daniels and Sara Ahmed

-

Tiana considers effective teaching to be an intersection of continuous co-constructed learning, self-confidence, and lifelong leaders that emerge from teacher teams and classrooms. Silvas feels that the best way to grow as an education leader is through experience in the classroom saying, “I continue to lead from the trenches.” She says “true leadership isn’t what you do in the moment, but the legacy you leave behind.” TIana is a 4th Grade Teacher, and former Literacy Coach at PS 59.

Tiana considers effective teaching to be an intersection of continuous co-constructed learning, self-confidence, and lifelong leaders that emerge from teacher teams and classrooms. Silvas feels that the best way to grow as an education leader is through experience in the classroom saying, “I continue to lead from the trenches.” She says “true leadership isn’t what you do in the moment, but the legacy you leave behind.” TIana is a 4th Grade Teacher, and former Literacy Coach at PS 59.

References:

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (2010). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group .

Ladson-Billings, G. “But That's Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy.” Theory Into Practice, vol. 34, no. 3, 1995, pp. 159–165. Summer.