By David Rockower

Vulnerability and engagement—I’d never used these words with middle schoolers. I’m sure I talked about taking risks and choosing topics of interest, but I never focused on the emotional and intellectual investment that often accompanies engaged learning. I was so focused on the particulars of teaching the content that I neglected to examine—with students—the power that comes from talking about how we engage and how we learn. As I continue to explore the answer to my research question—In what ways does teacher vulnerability impact students’ engagement and classroom community?—I’m learning about the elements of an authentic classroom.

This year, we are taking the time to understand the impact vulnerability has on learning and life. We are diving into the idea of engagement and how it leads to authentic learning (more on engagement in a future blog). We viewed short clips of Brené Brown discussing the power of vulnerability.

After my students gained an understanding of teacher vulnerability, I needed to clarify my own goals in terms of how it might improve my teaching. I created three dimensions of vulnerability:

Personal Vulnerability

Personal stories that share a failure, joy, a memorable moment, examples of our own artistic work: writing, painting, etc.

I often tell stories about my life. They typically involve funny moments, fond memories, and surprising interactions. Though these stories reveal parts of who I am, they are typically within my comfort zone. Recently, I pushed myself to read a poem I’d written about a shared moment with my daughter; this would be a real example of personal vulnerability. I was surprised at how nervous I was to read it to the class. When I shared, my students were locked in. There was no slumping in their seats, no side conversations, no staring out the window. Engagement, it seemed, was reciprocal; my vulnerability and engagement clearly translated to their engagement in my stories.

Relational Vulnerability

Teacher apologizing / admitting fault in the classroom, giving specific verbal or written compliments.

Relational vulnerability seems to happen more organically, in bursts. Whether it’s speaking too harshly to students on a bad day or rushing a lesson that required patience, I need to be willing to own my mistakes and apologize. Relational vulnerability also requires me to avoid vapid feedback: “Great work, interesting sentence, excellent participation.” Instead, I’m aiming for specific, meaningful communication: “The verbs in this sentence create imagery I can taste; I appreciate how you took risks in sharing an opinion that differed from the majority; thank you for stopping by to greet me each morning, because your kindness helps me start the day on a positive note.” I try to do more of this in person rather than on paper. There is tremendous power in looking a student in the eye and saying, “I’m sorry. I need to be more patient when you’re speaking,” or “I got chills when I read your memoir; it took me back to my own summers as a teenager.” It’s not always easy to be so honest and specific, but it communicates an authenticity that’s lacking in many classrooms.

Dialogic Vulnerability

Inviting crucial conversations in the classroom, even if these topics might create tension.

Dialogic vulnerability requires a shifting of power. Not only do I need to allow space for students to discuss real-world topics, I need to accept I may not be an authority on the issue at hand. In the past, the topics we’ve discussed and debated have been relatively safe. But my students want to talk about our school’s dress code and why it targets females; they want to engage in discussions about gun violence; they need to have conversations about race and privilege. I will need to look outside my classroom and invite colleagues, parents, and community members who are more knowledgeable than I to help facilitate some of these conversations. But when I do, I want to be a part of them; I want to allow our conversations to continue after the experts leave the classroom.

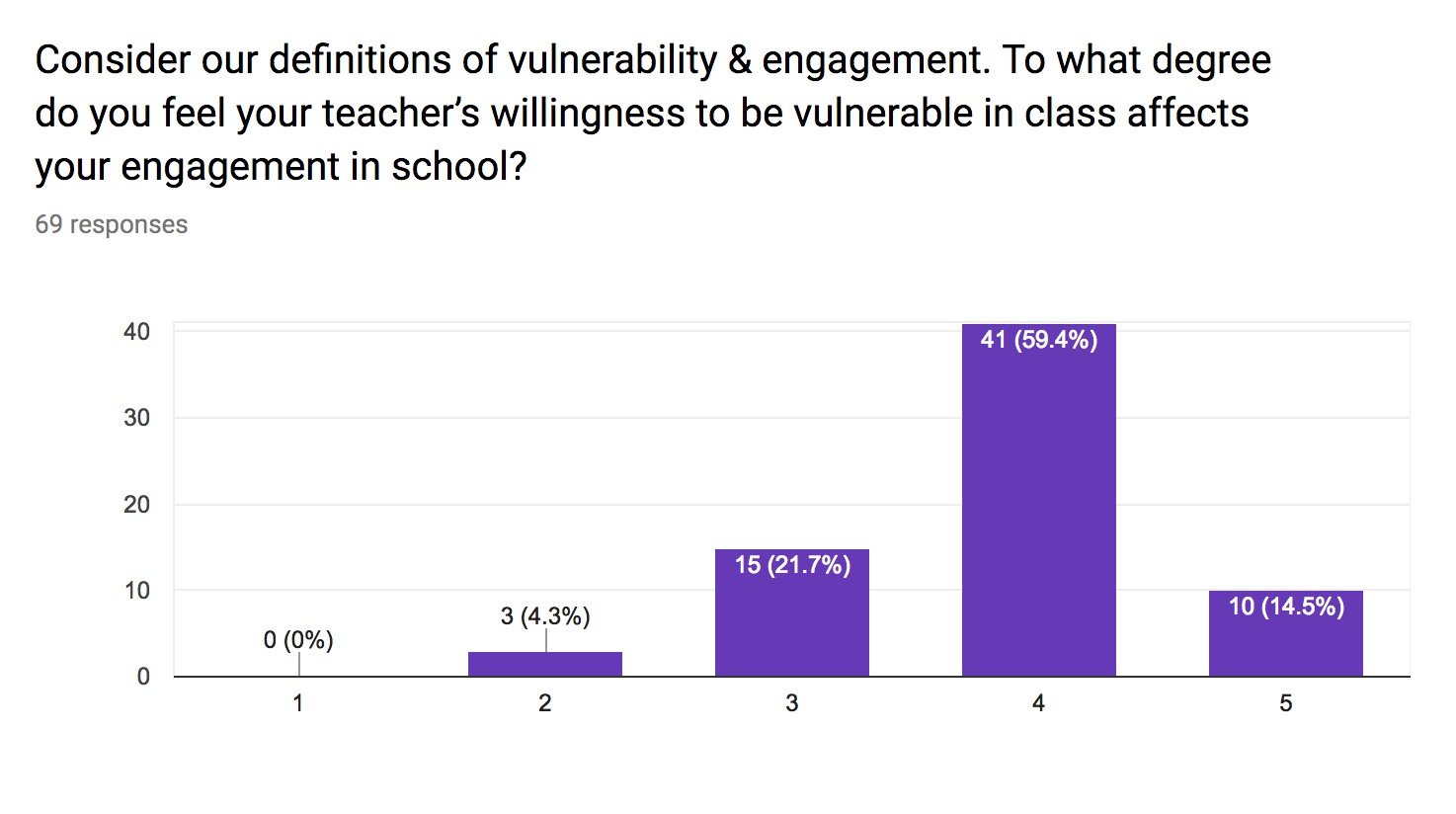

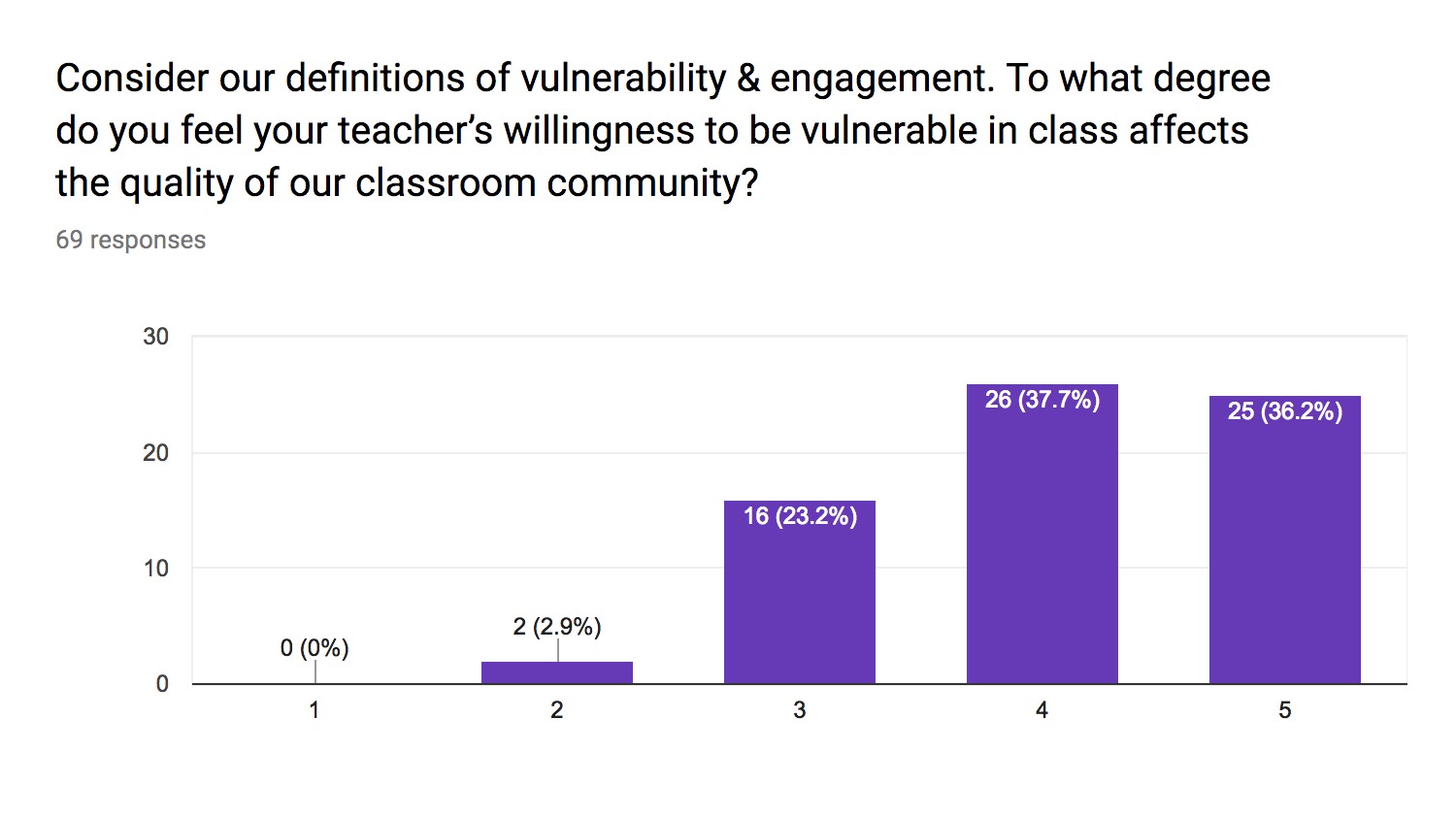

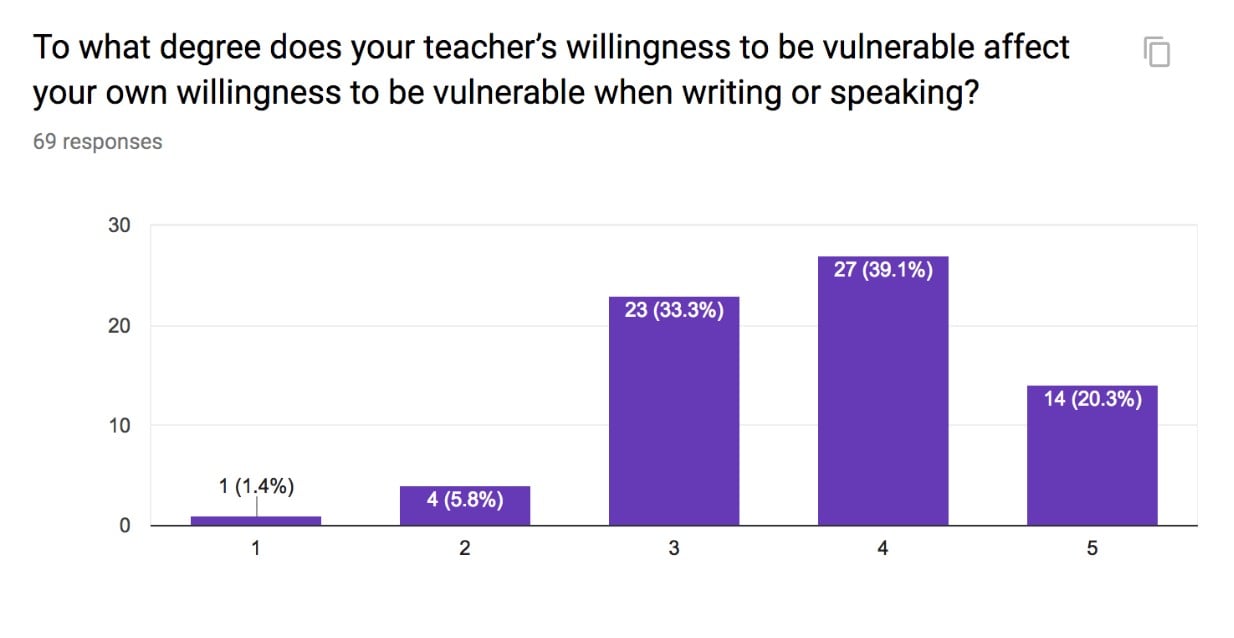

Early in the school year, after introducing vulnerability and engagement, I administered a survey designed to track our evolution in all three domains of vulnerability. Part of the survey included three short-answer questions, one for each dimension of vulnerability. The survey also asked students about the relationship between teacher vulnerability and engagement, which I will examine in future blogs. What follows is a sampling of student responses followed by data highlighting their answers to scaled questions.

Personal

When your teacher shares personal stories—through writing or speaking—does this affect the kind of stories you’re willing to share when writing and speaking? If so, how?

“Yes. I think seeing a teacher share something you wouldn't always share makes it less scary to do it yourself.”

“I think that it does help me feel more comfortable and able to share more, because I know about the teacher's personal life and who they are as a person, and not just a classroom teacher, so when I'm turning in my assignment, I don't feel like I'm sharing my personal life with a stranger.”

“In classrooms, the times when I have learned most, or really got into a topic is when a teacher has been vulnerable. I first got into math when a teacher told me how he had gotten into math. That really affected me and made me love it. It made me more vulnerable whenever I share stories—even ones not about math.”

Relational

Have you ever had a teacher apologize to you (individually or to the class as a whole)?* If so, how did this affect the classroom community and your relationship with that teacher?

“Yes but not sincerely. The few times that a teacher has apologized to me they have said it quickly and not meaningfully then continue to list all of the other things that I ‘did wrong.’”

“I've had a few teachers apologize, but in a way where you could tell they weren't sincere about it, so because the teacher didn't seem very sorry, relationships didn't really change.”

“Yes one time a teacher yelled at one of the students for taking a joke a to [sic] far, but the next time we had that class he said sorry, and I think it improved everyone's mood.”

*Approximately 40 percent of students indicated that a teacher never apologized to them.

Dialogic

Have any of your teachers facilitated discussions where opinions differ and emotions run strong? If so, how does this impact your engagement in the class? Also, how does it impact the overall sense of community?

“Last year, the discussion after the school walk-out was probably the most intense conversation I've ever been a part of, and I think that because of everyone's vulnerability, our community got much closer and connected.”

“I think that these conversations can be very strengthening if it is on a meaningful topic.”

“yes I think that it helps the community to see different opinions of other people other than yourself.”

“I've had some heated conversations in class before. I actually like those kinds of discussions because I can get my opinion out but also I can hear other people’s opinions including the teachers.”

Whether teacher vulnerability leads to an increase in student engagement is yet to be determined. However, the initial survey responses suggest students crave and appreciate authenticity. As I think about my research question and my students’ reactions to my vulnerability, I’m encouraged by their feedback and the overall sense of community we are creating together. Just the other day, a student asked, “Before we work, could you share another one of your stories? It gets me ready to open up and write.”

Whether teacher vulnerability leads to an increase in student engagement is yet to be determined. However, the initial survey responses suggest students crave and appreciate authenticity. As I think about my research question and my students’ reactions to my vulnerability, I’m encouraged by their feedback and the overall sense of community we are creating together. Just the other day, a student asked, “Before we work, could you share another one of your stories? It gets me ready to open up and write.”

David Rockower (Boalsburg, PA) believes that classrooms should be a second home for students, where they discover and celebrate strengths, where student voice, choice, and engagement are paramount. Currently, he teaches English at the Delta Program, a small, democratic middle school in the State College Area School District. He is also a bi-monthly essayist for State College Magazine and has published articles in The Washington Post and Education Week. In 2017, David was awarded as National Middle School English Teacher of the Year by the National Council of Teachers of English. You can follow him on Twitter @dgrock

David Rockower (Boalsburg, PA) believes that classrooms should be a second home for students, where they discover and celebrate strengths, where student voice, choice, and engagement are paramount. Currently, he teaches English at the Delta Program, a small, democratic middle school in the State College Area School District. He is also a bi-monthly essayist for State College Magazine and has published articles in The Washington Post and Education Week. In 2017, David was awarded as National Middle School English Teacher of the Year by the National Council of Teachers of English. You can follow him on Twitter @dgrock