It’s important to recognize and acknowledge the nuances of school leadership, culture, and accountability. Decisions that impact teachers and students do not begin and end with principals and assistant principals. It’s possible to have a school leadership team that is incredibly supportive of ABAR work but operates under a heavily resistant school board or other governing body. There are also principals who may commit to having your back verbally, but who fail to show up in practice when someone in the community pushes back.

In some cases, school leaders may be under the impression that they are doing effective and meaningful ABAR work, yet such initiatives must be scrutinized for surface-level performativity and for whether or not they are based on deficit ideologies. While classroom teachers can certainly impact the culture of a school, there are often structural issues that cannot be resolved by one person.

These problems exist because they are systemic in nature. They require the redistribution of power within the organization. Classroom educators have a responsibility to participate in this work and advocate for more inclusive and equitable learning environments; however, systemic work and shifting a community’s culture takes time.

When you’re hired as a classroom teacher, your realm of responsibilities is fairly clear: instructing students, planning and preparing lessons, grading, communicating with families, and possible additional requirements like supervising lunch and recess, or leading a club or coaching a sports team. (This list does not include additional roles teachers end up taking on without financial compensation, such as mentoring, providing resources, emotionally supporting students and families.) Principals and assistant principals wear multiple hats, many of which are swapped on and off throughout one school day.

Also, there is a perception that people in leadership positions hold more knowledge than other employees, so they must have the answers to difficult-to-answer problems. As simple as this may sound, school administrators are just as human and prone to self-doubt and uncertainty as any teacher. No one wants to be judged as someone who doesn’t understand issues surrounding diversity or antiracism. Administrators are fearful of using the wrong language, offending people in the community, being misunderstood, and hearing the angry parent on the phone demanding to know why the school is forcing a political agenda on their children. If school leaders are not experienced in having challenging conversations or developing fluency around ABAR either in their own lives or within the school community, it’s easy to see how these attitudes and behaviors can trickle down to faculty and staff.

It is important to find fellow supporters for the purpose of building large-scale capacity for this work. If there are like-minded staff members at your school, even in different grade levels or departments, how can you work together? Form a partnership around an activity, unit, or culminating event. If your school leadership is resistant, having a partner in the room feels drastically different from facing your principal alone.

Families and caregivers are also incredible assets. They often raise powerful voices when it comes to addressing the needs of a school. How can they support you? Perhaps families and caregivers can

- email your school administration in support of ABAR work

- ask to be included in stakeholder meetings

- collaborate with teachers (especially if your school has a director of diversity or a diversity committee) to organize parent and caregiver workshops or book clubs to support ABAR at home

- interview other families of diverse backgrounds about their experiences at the school, and how inclusion efforts can be improved.

Together, partnerships between teachers and caregivers further support the case for how ABAR must be ingrained in the culture of your school, as there are shared values between school and home.

We can work to identify the ways in which educators can work with school leaders and even families and caregivers to teach from an ABAR lens, and to address any perceived lack of support for ABAR implementation from administrators or school leaders who are wary of how it may be executed in the classroom.

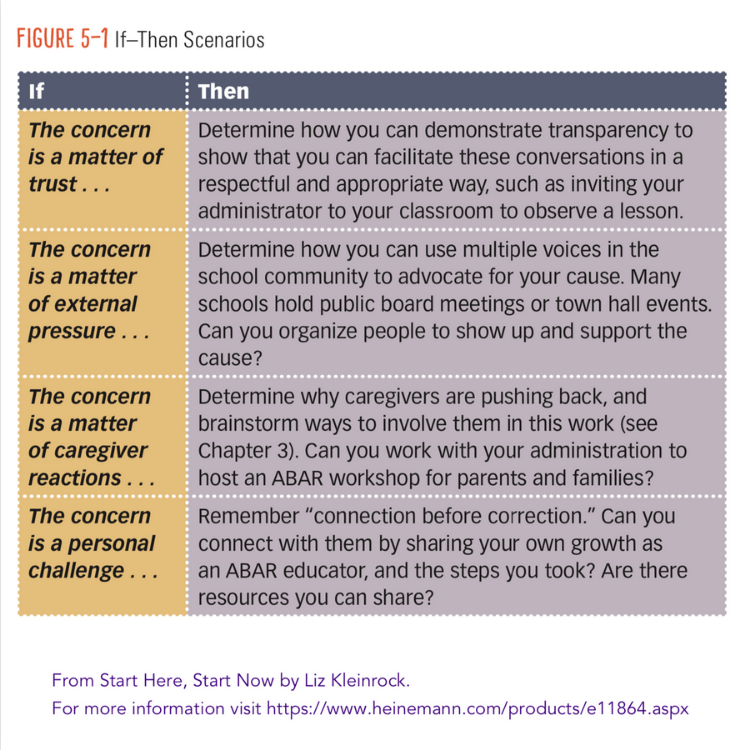

Being able to identify why there is reluctance or skepticism will guide you in making an actionable plan that reflects your understanding of the positions, and how you plan to directly address the concerns.

Find the Root of the Concern

In any situation that requires problem-solving, we have to identify the root of the concern. You can start by thinking about your unique school community. The language and methods teachers utilize may differ depending on the type of school and its stakeholders. For example, one principal may be more concerned with how tuition-paying family members push back, while another may be focused on teachers aligning their lessons with standards or preparing their students for standardized assessments. Some school leaders may be under pressure from the superintendent or board members. Being able to identify why there is reluctance or skepticism will guide you in making an actionable plan that reflects your understanding of the positions, and how you plan to directly address the concerns. In Figure 5–1, you will find some possible if–then scenarios.

There is no blanket strategy for ABAR, so you must take your context into consideration. For educators who work in districts with strong unions, it will be easier to shift your teaching practices. For others who teach in places where if you upset your administration you can quickly be deemed ineffective and lose your job, you have to weigh your risks and determine what changes you can make within your control. For example, if your principal is adamant about following standards, carefully review them and your curriculum to determine if you can isolate standards and supplement additional materials to teach the particular topic. However, remember that ABAR is a lens, and your curriculum is just one aspect of your practice. Even if your administration is unsupportive of curricular integration, there is important self-work to do as a teacher, as well as intentionally creating the culture of your classroom.

To learn more about this book visit Heinemann.com.