This blog post was adapted from Risk. Fail. Rise. A Teacher’s Guide to Learning from Mistakes by Colleen Cruz.

The idea—that we maintain mistakes so that we can avoid correcting a false belief—is a fairly new idea to me. I first heard about it from architecture, of all places. One of my friends is a city planner in DC and told me these kinds of mistakes you see in architecture have a name: Thomassons. The term was coined by the Japanese artist Genpei Akasegawa, who called elements in a city that were useless but nonetheless looked like conceptual artwork hyperart (Akasegawa 2010). He later specified a particular kind of hyperart as a Thomasson, describing architectural elements that are:

- completely and utterly useless

- being maintained

You recognize them when you see them. Although if you’re anything like me, you didn’t realize there was a name for them. Thomassons can be found in perfectly preserved signs for buildings that no longer (or never did) exist, doorways that lead to walls or nothingness, stairways that lead to nowhere. These are things whose original purposes have long been forgotten, maybe never even fulfilled, but somehow the object in question continues on. Very often they are mistakes in architecture that were never addressed.

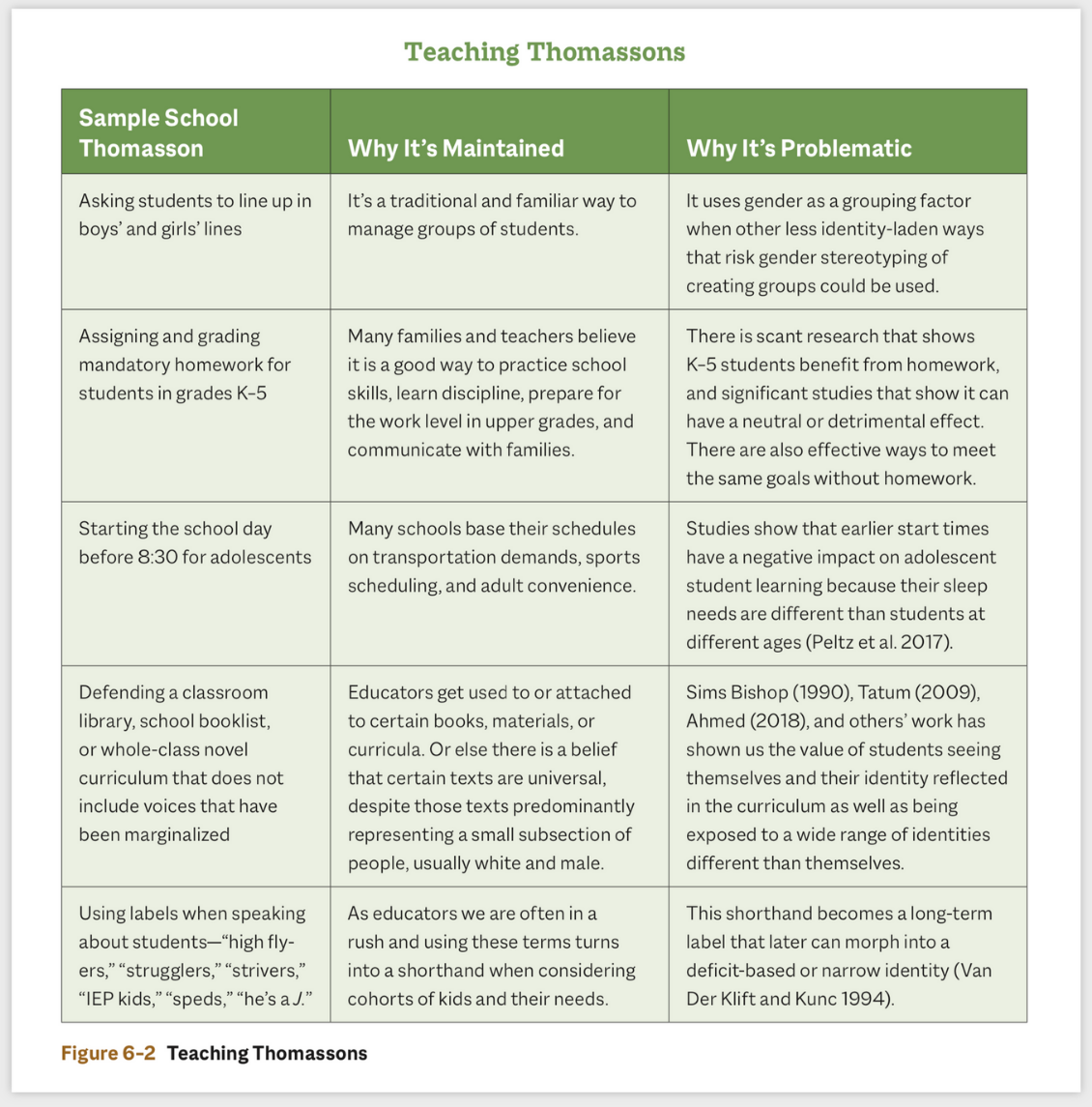

Thomassons remind me of so many things we do in teaching. Such as that writing graphic organizer we introduce in September to help kids plan their stories. We are convinced that they will really love it. And they try it. But then eventually they stop using it. I stop teaching it. But I still keep photocopying it or uploading it and putting it in the writing center. Useless. Maintained. Or that way we teach vocabulary, which is the way our childhood teachers taught us vocabulary. We tell students to use bigger words whether the words fit or not and to replace perfectly good words like said with words like stated, mumbled, and declared, even though we notice that professional writers almost exclusively use said. Even though we notice our kids keep using said or using those other words badly, we hang up a tombstone over our E-Board that says, SAID IS DEAD. And make a big bulletin board with synonyms of said. We know it doesn’t feel right. We know it’s not working. We know it’s a mistake, yet we maintain it.

↓ CLICK TO DOWNLOAD AND PRINT ↓

Stop for a few minutes and reflect a bit on one of your teaching Thomassons. Think of a practice or habit that you employ knowing that it’s either wrong or just plain useless. This might be harder to do than it seems at first glance. This work of identifying a place where we are making a mistake can be daunting. Whether it is excusing myself for forgetting to pick up bread when my wife asked me to because I had so many other things on my mind, or spelling an author’s name wrong on a citation (autocorrect!), I have realized I make a lot of excuses or self-justifications.

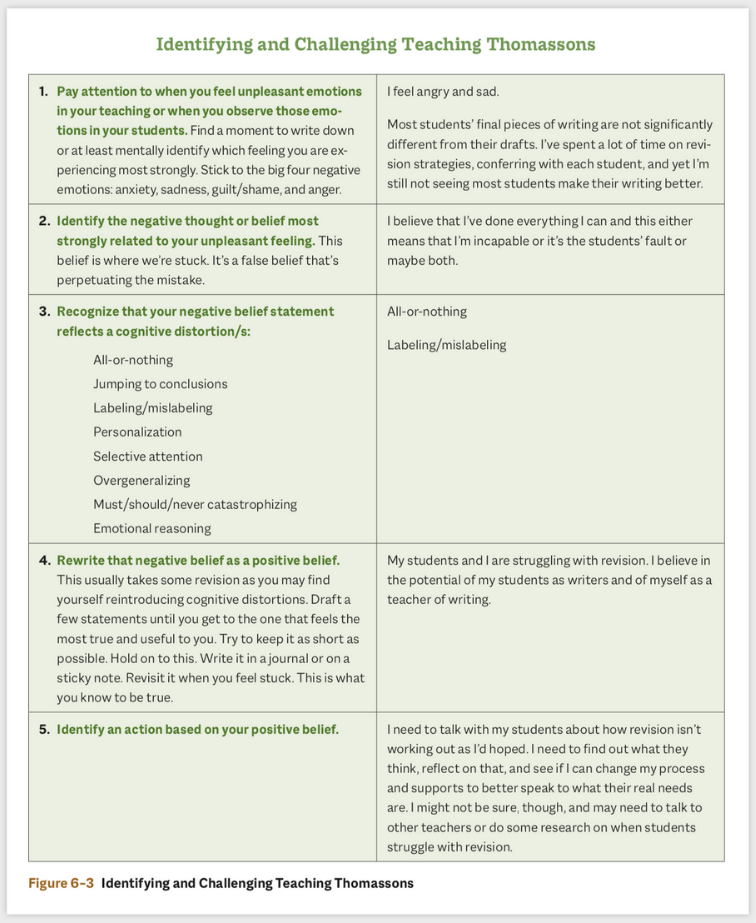

So, if you’re sitting there drawing a blank, I’d like to give you a few lenses to help you reflect. Study yourself for a day or ask a colleague to weigh in. You might even want to take low-inference notes for a day on everything you do and then reflect on it later when you’re not with students. But because of how often teaching Thomassons are connected to a false belief, these can be very difficult to spot in ourselves. Often the most reliable path is to pay attention to our emotions in our teaching so that we can identify and challenge mistaken beliefs and replace them with accurate thinking. This process, pioneered by Albert Ellis (1997), Aaron and Judith Beck (2011), among others, is called cognitive restructuring.

See Figure 6–3 for an example of how the cognitive restructuring process can help us spot our teaching Thomassons.

↓ CLICK TO DOWNLOAD AND PRINT ↓

We know that repeated thought patterns create well-worn paths in the brain that we default to more easily than new thinking. Giving up a teaching Thomasson is not easy, even if it’s a simple thing. When it seems simple, try envisioning your Thomasson as a sapling; it might look small, but the negative belief usually has strong roots. Again, that’s why it’s important we revisit our positive belief statements. They remind us to focus on behaviors that directly relate to that positive belief statement.

For me, Thomassons are one of the most humbling types of mistakes that I make. Mainly because these are not one-time instances nor are they “innocent.” I know better, and yet I keep repeating them. Having a protocol and knowing that it is never too late for a do-over helps me avoid lingering too long on self-flagellation. As we all look at our personal Thomassons and become more aware of the systemwide Thomassons, it is important to remember that no matter how long we have been making, maintaining, and defending mistakes, once we realize that we are mistaken, no matter how painful that realization is, it is time to rid ourselves of our Thomassons once and for all.

REFERENCES:

Akasegawa, Genpei. 2010. Hyperart: Thomasson. Los Angeles: Kaya Press.

Beck, Judith. 2011. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York: Guilford Press.

Fan of Podcasts? Listen to a recent conversation between Colleen Cruz and Nell Duke.

• • •

In addition to being the author of The Unstoppable Writing Teacher, M. Colleen Cruz is the author of several other titles for teachers, including Independent Writing and A Quick Guide to Helping Struggling Writers, as well as the author of the young adult novel Border Crossing, a Tomás Rivera Mexican American Children's Book Award Finalist. Colleen was a classroom teacher in general education and inclusive settings before joining the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project where she is Director of Innovation. Colleen presently supports schools, teachers and their students nationally and internationally as a literacy consultant.