The following is an adapted excerpt from Kelly Gallagher’s forthcoming To Read Stuff You Have to Know Stuff, Available for preorder now.

What happens when a reader lacks prior knowledge? Let’s try a word in isolation. What comes to your mind when you read the word contig? My guess? Not much more than What the heck does contig mean? If you don’t know what a contig is, and there is no context to figure it out, it won’t matter if you are a proficient reader.

It won’t matter that you have phonemic awareness or a high degree of fluency. It won’t matter if you apply word-attack skills or are highly motivated to figure it out. Your inability to understand the word is rooted in the fact that you have little or no background with the word to draw upon. No strategy from your reader’s tool belt is going to help you. Without prior knowledge, making meaning may be impossible. (For the uninitiated, a contig “is a series of overlapping DNA sequences used to make a physical map that reconstructs the original DNA sequence of a chromosome or a region of a chromosome” [Green 2024].)

Reading the text is one thing; being able to read while accessing prior knowledge is another. What we attach to our reading is what gives our comprehension nuance and depth.

The Importance of Owning Information

You may have heard the argument that students don’t need to know information because we live in an age where they can just look things up. After all, everything they might need to know is as close as their phones. So, instead of teaching them stuff, what we really should be doing is teaching them how to think.

Well, yes and no.

Certainly, we want to teach students to think critically, but this is not an either-or case. In fact, quite the opposite. Alongside the teaching of critical thinking skills, it is imperative that we also teach kids stuff. Lots of it. Why? Students who know more are able to learn more, and they are able to learn easier. Daniel T. Willingham, professor of psychology at the University of Virginia and author of The Reading Mind: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding How the Mind Reads (2017) notes that those who possess knowledge find learning to be easier. This is because “factual knowledge enhances cognitive processes like problem-solving and reasoning. The richer the knowledge base, the more smoothly and effectively these cognitive processes—the very ones that teachers target—operate” (Willingham 2006).

There are a number of studies to support this. In one study, David Hambrick (2003) tested college students about their knowledge of basketball during the middle of the season. He tested students again two and one-half months later at the end of the season. Hambrick found students who knew more about basketball prior to the experiment learned more as the season progressed. Having knowledge was a major factor when it came to their learning. Their prior knowledge provided a base and thus enabled them to more easily grow new learning.

Diverse Sources of Background Knowledge

These findings are applicable beyond reading about sports. Recht and Leslie (1988) cite studies that came to the same conclusion when students read about diverse topics such as computer programming, electronics, chess, and bridge (as noted by Willingham 2006). Interestingly, the researchers found that both “good” and “poor” readers had similar levels of recall when the text was familiar to them. The “poor” readers, however, were significantly less likely to recall what they read after reading unfamiliar text.

The notion that prior knowledge helps grow new learning is true across the curriculum. In a math class, for example, already knowing how to divide numbers will help you immensely when you are first asked to learn how to compute percentages. In a social studies class, you cannot glean a deep understanding of the Russian invasion of Ukraine or the Israel-Hamas war unless you possess knowledge of the history of those regions. In an earth science class, a deeper understanding of earthquakes comes to those who already possess an understanding of the architecture of the earth. And so on.

Additionally, prior knowledge not only plays a critical role when it comes to reading but also plays an even more crucial role when it comes to writing. It is not a coincidence that almost all my best high school writers were students who had broad reading backgrounds. You have to know stuff to read stuff, but you really have to know stuff to write stuff.

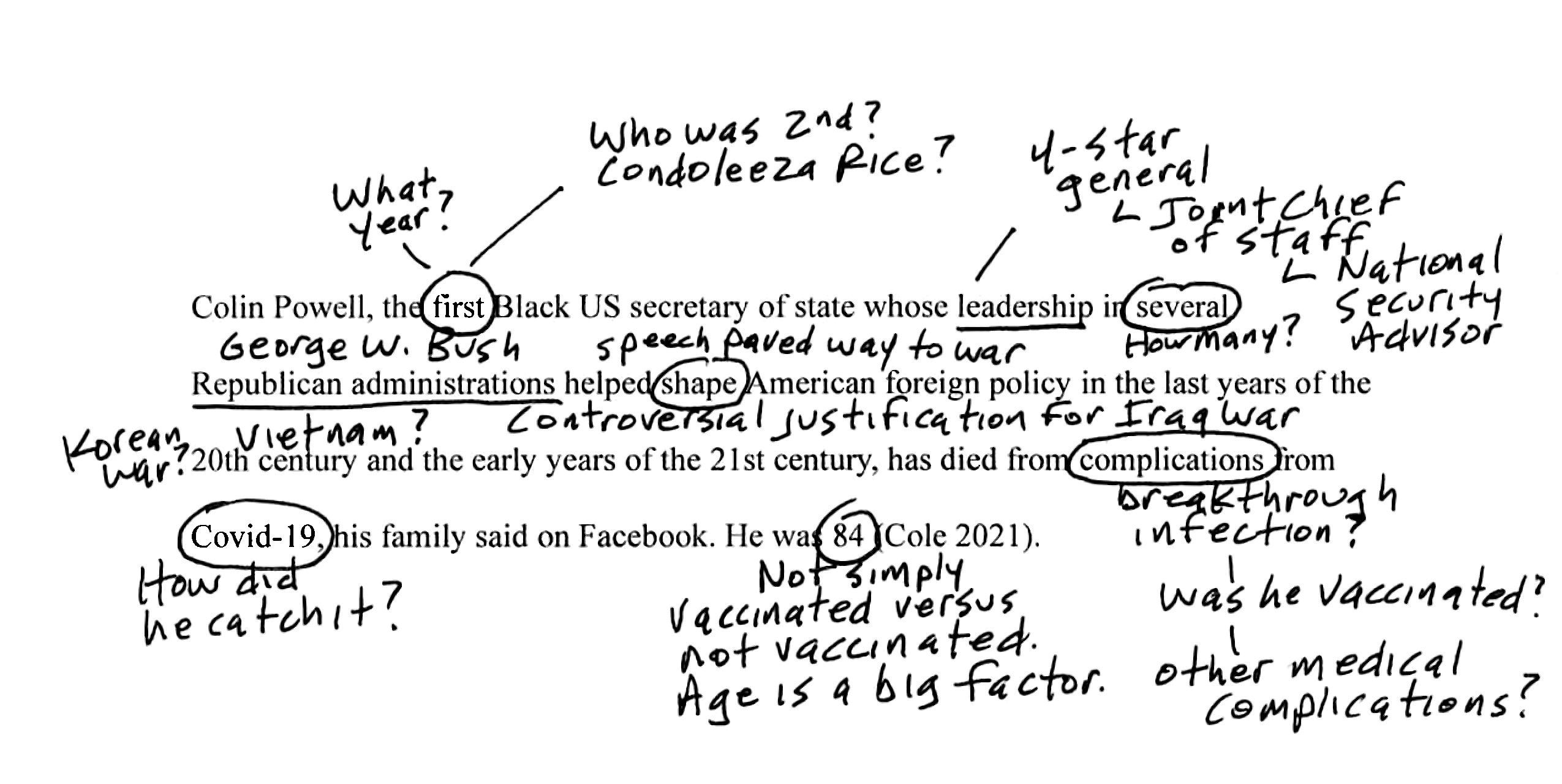

I discovered the news of Colin Powell’s death via this two-sentence news bulletin. The figure above shows where my mind went as I read it.

In reading this short passage, I deepened my comprehension by connecting what I was reading with what I already knew. Specifically, I did the following:

- made a connection to Powell’s successor, Condoleezza Rice

- recalled key moments in Powell’s military and political career

- remembered his appointment by President George W. Bush (and his subsequent resignation)

- recalled his speech that proffered a controversial justification to pave the way to war (All these years later, I can still visualize exactly where I was sitting while listening to Powell give his infamous speech.)

- considered Powell’s vaccination status and wondered whether this may have been a breakthrough infection

- made a connection to an article I recently read about the virus’ magnified effect on the elderly

- wondered if Powell had preexisting conditions

When it came to reading about Colin Powell, it was not simply reading the words on the page that led me to deeper reading. It is what I brought to the page that deepened it.

Kelly Gallagher and Penny Kittle recently visited the Heinemann podcast to discuss engaging students using book clubs. Listen here.

Free Event—Helping Readers Build Prior Knowledge Presented by Kelly Gallagher

Book Description

In the age of click-and-go reading, why do students need to know information when they can just look things up?

Bestselling author Kelly Gallagher argues that to think critically, it’s imperative that we teach kids stuff. Lots of it. Why? Because students who know more are able to read more, and read better.

In To Read Stuff You Have to Know Stuff, Kelly draws from his own teaching practice to share the importance of building students’ prior knowledge at four levels:

- Words: How building knowledge helps students to overcome word poverty

- Sentences and Passages: How building knowledge helps students to comprehend “small” reading

- Articles: How building knowledge helps students to critically read articles—an important skill in our digital age

- Books: How building knowledge moves students away from fake reading and back into reading full-length books

To Read Stuff You Have to Know Stuff also shows how students can monitor their own comprehension. They can see that many reading difficulties aren't the result of not being a "good reader"— they simply lack knowledge.

Our students are fortunate to live in an age where so much information is a click away. But to read well—and think well—they need to own that knowledge.