Adapted from A Teacher’s Guide to Using AI by Meenoo Rami.

As a teacher, you’ve likely felt some pressure to use AI or to teach your students how to use AI. However, it is also crucial that today’s young people are taught about AI, not just how to use it. This means helping students to understand what AI is, how it works, who it benefits, who it hurts, how it can be helpful, and how it can be dangerous. Teaching students about AI is not just about keeping pace with technological advancements; it’s about preparing students to navigate, critique, and contribute to a society increasingly influenced by these systems. By equipping students with the skills to understand and use it responsibly, you empower them to become informed citizens, ethical users, and innovative creators.

Your students are already tinkering with, playing with, and trying to figure out AI for their own use. They are understandably curious. Can it tell them about the things they want to know about? Can it help them create things they couldn’t create on their own? Can it help them navigate the day-to-day stresses of their lives? Can it lighten the load of their schoolwork?

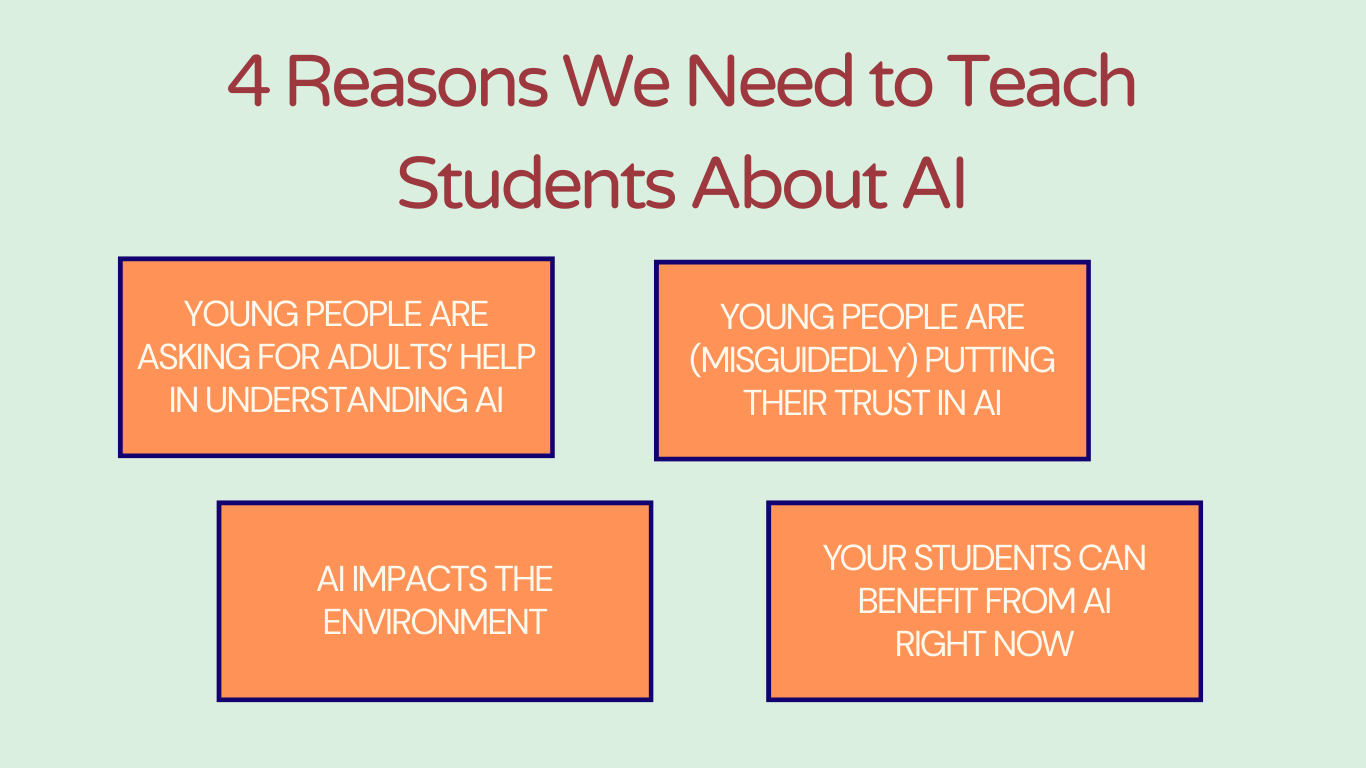

Let’s consider 4 reasons why it’s necessary to teach students about AI.

Young People Are Asking for Adults’ Help in Understanding AI

Teens are very much aware of the risks involved in using AI and are looking for guidance and guardrails (Hopelab et al. 2024). This alone is a strong argument for why kids should be taught about AI and how to use it: they are asking for your help.

Young People Are (Misguidedly) Putting Their Trust in AI

The most common use of AI by teens is finding information (Hopelab et al. 2024). This is understandable: AI can give an exact answer to a specific question rather than links to sources that, if scanned and scoured, could give the searcher the answer they’re seeking. Unfortunately, there’s no guarantee the information an AI tool provides is accurate. While there’s no age limit on people’s ability to believe false information, younger people have had less time to accumulate the life experiences and general knowledge that is the basis for crystallized intelligence, the ability to apply what one has previously learned to a new situation. This makes it more difficult for them to detect false information at first glance (Kelly 2024).

Students are also at risk for putting trust in AI agents. As of 2025, 72 percent of US teens say they have used AI for companionship, with slightly over half of all US teens using AI for companionship somewhat regularly (Robb and Mann 2025). Researchers at the University at Surrey found that even when people form relationships with AI agents to stave off loneliness, the agents are “addictive” and “doing more harm than good” (University of Surrey 2023).

AI Impacts the Environment

AI relies on massive infrastructure, including climate-controlled data centers the size of university campuses. Amazon® has over 100 data centers around the world; Microsoft is building fifty to 100 data centers each year. Each data center houses around 50,000 servers. Scientists have calculated that the energy used in these data centers just to train GPT-3 could have powered 120 homes for a year. That training also released over 500 tons of carbon dioxide into the environment. Training also leads to fluctuations in demand on power grids. To stabilize, the grids depend on diesel-run generators. To be clear, this is all for training a single model. Every new model requires fresh training. Once a model is trained, responding to a prompt uses five times the energy needed to power a web search. Soon, generative AI’s power demand could rival that of countries such as Sweden or Argentina. By 2030, some projections expect AI data centers to consume as much electricity as all of Canada and warn that AI’s carbon emissions will grow by over ten times their current amount. Additionally, data centers need a great deal of cold water to keep equipment cool, leading to drains on municipal water supplies (Zewe 2025; Dalton and Brocius 2024; Geman 2025).

Not all AI has the same impact on the environment. Predictive AI uses smaller, specialized datasets on very specific tasks, such as detecting pollution and predicting weather. It needs much less energy than generative AI to do its work (Dalton and Brocius 2024). Predictive AI has the potential to support climate solutions, not just create new problems.

Students are inheriting a world shaped by AI. They deserve to understand what it costs. Understanding the environmental trade-offs of AI can help them consider the effects of their own use of AI.

Your Students Can Benefit from AI Right Now

Much discussion about AI and young people is about how AI will be essential to them later in life as a tool in their work, or how AI will someday evolve into being a more powerful tool than we have access to today. While that may be true, there is still a great deal that AI agents can do for your students right now, from brainstorming to tutoring to creating to translating. Understanding how the tools work, the aims for which they were shaped, and the ways in which they use the information users feed them can help students to make informed decisions about how, when, and why to use AI tools.

A Teacher’s Guide to Using AI is an essential companion for educators navigating the rapidly evolving world of artificial intelligence in schools. Meenoo Rami, a former classroom teacher and longtime advocate and builder of thoughtful technology in education, offers clear, specific, actionable guidance to help educators understand, incorporate, and make sense of AI’s role in the classroom, including:

- practical strategies for using AI in your own work to save time, personalize instruction, communicate with caregivers, and spark creativity

- integrating AI into lesson planning, creating and refining assignments, planning curricula, analyzing student data, and providing feedback

- guidance for teaching students about AI’s capabilities, limitations, ethical considerations, and potential risks as well as how it can supercharge their learning and agency

Sources

Dalton, Greg, and Ariana Brocious. 2024. “Artificial Intelligence, Real Climate Impacts.” Climate One. Podcast, Apr. 19. https://www.climateone.org/audio/artificial-intelligence-real-climate-impacts

Geman, Ben. 2025. “New Study Shows AI Emissions Path—and How to Bend the Curve.” Axios, June 25. https://www.axios.com/2025/06/25/ai-emissions-accenture-study

Hopelab, Common Sense Media, and the Center for Digital Thriving at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. 2024. “Teen and Young Adult Perspectives on Generative AI: Patterns of Use, Excitements, and Concerns.” June 3. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/research/report/teen-and-young-adult-perspectives-on-generative-ai.pdf

Kelly, Mary Louise. 2023. “‘Everybody Is Cheating’: Why This Teacher Has Adopted an Open ChatGPT Policy.” NPR, Jan. 26. https://www.npr.org/2023/01/26/1151499213/chatgpt-ai-education-cheating-classroom-wharton-school

Robb, Michael B., and Supreet Mann. 2025. Talk, Trust, and Trade-Offs: How and WhyTeens Use AI Companions. Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/research/report/talk-trust-and-trade-offs_2025_web.pdf

University of Surrey. 2023. “Popular AI Friendship Apps May Have Negative Effects on Wellbeing and Cause Addictive Behaviour, Finds Study.” Oct. 19. https://www.surrey.ac.uk/news/popular-ai-friendship-apps-may-have-negative-effects-wellbeing-and-cause-addictive-behaviour-finds

Zewe, Adam. 2025. “Explained: Generative AI’s Environmental Impact.” MIT News, Jan. 17. https://news.mit.edu/2025/explained-generative-ai-environmental-impact-0117