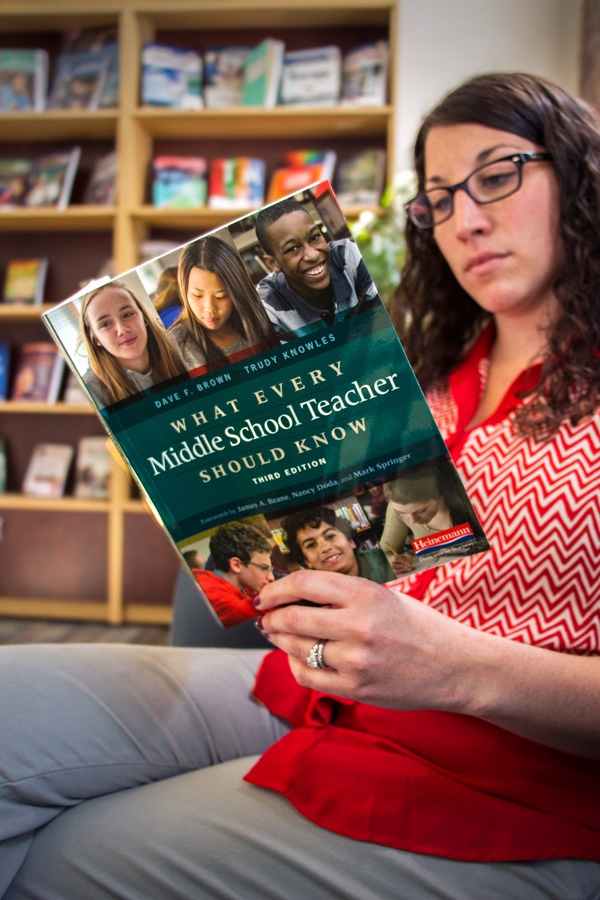

Researchers Dave Brown and Trudy Knowles have updated their bestselling classic What Every Middle School Teacher Should Know with more student voices, as well as timely new research, strategies, and models that illuminate the philosophies and practices that best serve the needs of young adolescents. In this entry in a special blog series Dr. Brown writes about the social challenges students face today. (To read part one of the series click here: Part One. To read part two of the series click here: Part Two)

Researchers Dave Brown and Trudy Knowles have updated their bestselling classic What Every Middle School Teacher Should Know with more student voices, as well as timely new research, strategies, and models that illuminate the philosophies and practices that best serve the needs of young adolescents. In this entry in a special blog series Dr. Brown writes about the social challenges students face today. (To read part one of the series click here: Part One. To read part two of the series click here: Part Two)

Gracie, one of fifty eighth graders surveyed for this new edition of What Every Middle School Teacher Should Know, reveals the social challenges of middle school:

Gracie, one of fifty eighth graders surveyed for this new edition of What Every Middle School Teacher Should Know, reveals the social challenges of middle school:

"Every middle school teacher should know that as students we come to school to learn. But we also come to make friendships that could be very valuable to our future. We don’t always have the best days because there are some pretty mean kids who try to bring you down. So those friendships we build help us to get through the day and enjoy learning, which is what we should do. " (p. 38)

Gracie is referring to the face-to-face encounters that middle schoolers experience each day, but with the explosion of technology via smart phones and Internet social sites, young adolescents are likely to feel just as much pressure socially away from school as they do at school. Smart phones have increased tenfold the opportunities for teens to communicate with one another—especially by texting—immediately and often, with little concern for or awareness of the effects of their words, pictures, or videos.

When my younger daughter was in seventh grade, a parent of a sixth grader admitted that though she didn’t want to purchase a cell phone for her daughter, she felt she had to because most of her daughter’s friends had one. When is the “right” time to purchase a young adolescent a smart phone? I’m not qualified to answer that question, but knowing the social, emotional, cognitive, and identity-development immaturity of ten-to-fifteen-year-olds, I wouldn’t suggest handing them their own phone much before the age of fourteen. But the pressure builds, and which sixth grader wants to be the last one in her peer group to get a cell phone?

Once all middle schoolers have a cell phone, what will they do with them and how will they affect their social lives? Calling these technological devices phones is absurd, because teens aren’t using them to call anyone. Taylor, another student surveyed, admits, “Phone calls have much deeper meaning; we only call to clarify misunderstandings in text or Facebook messages and tweets” (p. 40). If Facebook and text messages have replaced face-to-face friendships, then the adults in teens’ lives need to know enough about what’s happening to determine how teens are affected by these social interactions.

Our new edition reports several findings from the 2013 Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project’s study of over 800 adolescents (Madden 2013). For instance, 81 percent reported having Facebook accounts, each with an average of 300 friends. I don’t think I’ve had 300 friends in my entire life, but the word “friend” has an entirely new meaning for this generation. These Facebook conversations have a serious effect on teens. One fourteen-year-old girl admitted, “On Facebook, people imply things and say things that they wouldn’t say in real life, ” and a thirteen-year-old girl noted, “I feel like on Facebook people can say whatever they want to . . . [and] if they say something mean, it hurts more” (p. 41). Hidden from the halls and classroom social milieu, adults miss these encounters—and that can be costly to the emotional lives of young adolescents. Snapchat adds to the instantaneous messaging back and forth among adolescents, some of it fun, but many of these pictures are just as likely to be socially damaging. All of a sudden, parents aren’t sure purchasing that cell phone for their twelve-year-old was a good thing after all.

Keeping track of all of these Facebook friends is time-consuming. Teachers should be initiating conversations with their students about their “online” and smart phone lives. These conversations can be initiated with an entire class through an advisory session or individually with students when they appear to be struggling socially or emotionally. As we suggest in Chapter 3, “‘Teaching’ young adolescents how to manage their time and social interactions online is a new responsibility for parents and teachers—yet a critical lesson for teens” (p. 41). The effect of technology on adolescents’ lives is an entire new section of the third edition; middle-level educators need to adopt strategies to address these issues.

To learn more about the third edition and to read a sample chapter, click here.