by Heinemann Fellow Julie Kwon Jee

Looking back on my high school experience, I believe there could have been a lot more diverse texts. I believe that a lot of the texts I read were just the traditional texts that students have been reading for years and years.

—Alyson S., former student

Thank you for bringing these issues to the department's attention. Change is hard and when things have been entrenched for hundreds of years, it is even harder.

—Michael R., colleague

My twelfth graders dutifully called out the names of some of the texts they had read in previous years for English class as I wrote them down one by one: The Great Gatsby, Hamlet, Maus, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Crucible, Of Mice and Men, Lord of the Flies, And Then There Were None, Romeo and Juliet, Fahrenheit 451, Farewell to Manzanar. The titles filled the whiteboards around my classroom. I thought of the books we would be reading during the 2019–2020 school year—The Oedipus Cycle, Macbeth, Everything I Never Told You, The Road, and No Exit. One title by an author of color on the boards. One title by an author of color on my list. I felt frustrated and overwhelmed.

On paper, it looked like progress. The intent behind my Heinemann action research project seemed to have merit—diversify the summer reading lists and the curriculum for my twelve AP Literature students. When I looked at the list in June 2018, out of forty-six titles, only five were by authors of color. White heterosexual voices dominated while BIPOC (Black, indigenous, people of color) and/or LGBTQ+ authors were rare. My seniors were eager to work on improving this ratio, so over the course of the 2018–2019 school year (as documented in our Instagram account), they moved outside their comfort zones and chose books by and about diverse authors and characters. I, along with my wonderful school librarian and an amazing local bookseller, did numerous book talks. In the classroom, my students worked on independent reading journey projects and book stacks (student sample 1 and student sample 2) inspired by NCTE’s Build Your Stack posts. We audited our classroom library and took note of the voices that were featured and those that needed to be represented better. The feedback was enthusiastic, and in June 2019, the final results for my first year looked promising—we expanded the summer reading titles by almost 50 percent and added diverse authors across every grade level. The new lists looked good. I felt good.

But then I didn’t.

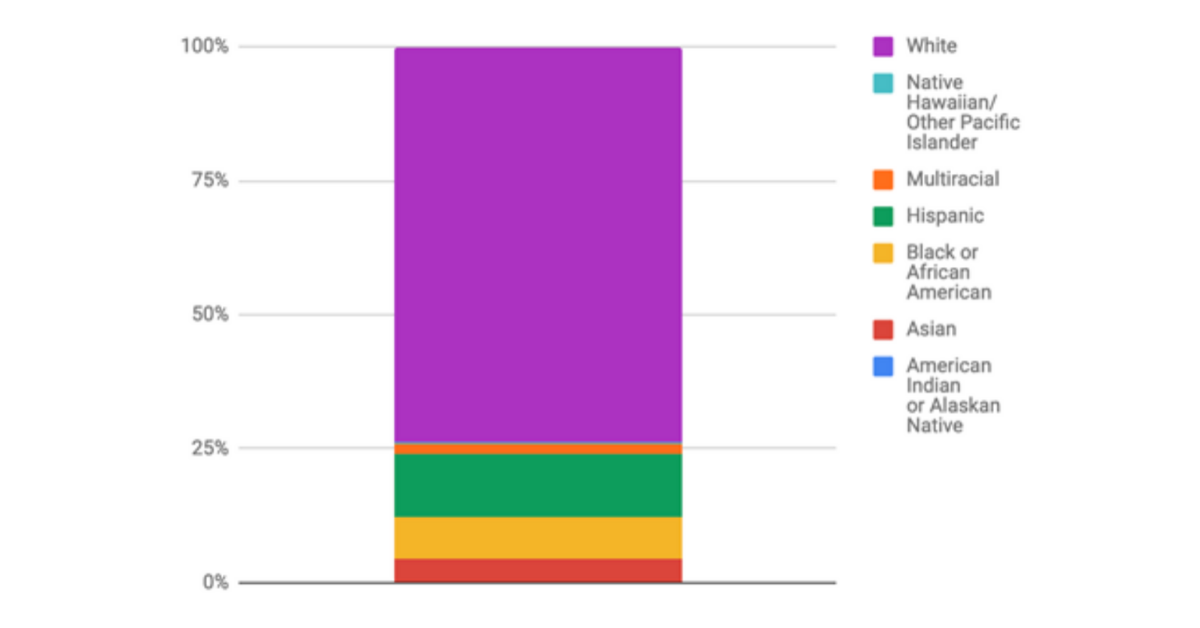

Student body (as of 2017):

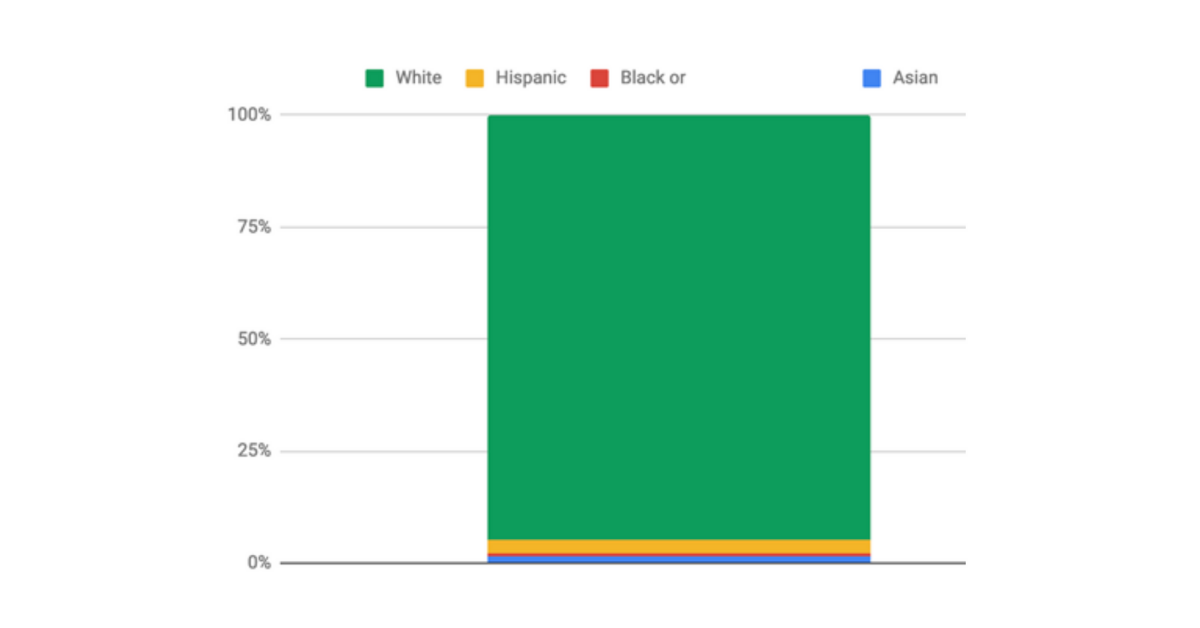

High school faculty (as of 2017):

The vast majority of the books that my colleagues and I teach are written by white authors. To a certain extent, this reflects our demographics. As of 2017, 74 percent of the student body at my high school identify as white; twelve percent identify as Hispanic, eight percent identify as Black, four percent identify as Asian, two percent identify as multiracial, and less than one percent identify as Native Pacific Islander or Native American. Ninety-five percent of the teachers at my school identify as white. The changes in the summer reading lists represent a positive shift toward introducing and validating diverse perspectives, but these documents are merely glanced at by students (often under duress) during the break and then put away for the remainder of the school year. It was easy for me and my seniors to celebrate the addition of these titles, but what lasting changes were accomplished? The change is incremental, when our approach and its effect should really be seismic in nature.

After numerous conversations and hours spent listening to fellow educators in my department and on Twitter through phenomenal chats including #DisruptTexts, #TheBOOKCHAT, and #ClearTheAir, I knew that a deeper dive into the issues of the centering of white supremacy and the lack of representation of LGBTQ+/BIPOC identities was and is necessary. There also needs to be a synchronous look at our own identities and how they have affected who we are and how we approach and study literature. I know this will be an ongoing process for me, as I continue to learn and fail and work to move past my biases about what literature is. I am not alone in this. I know many of my colleagues are making efforts to expand their classroom libraries and read titles that reflect experiences they may not be familiar with. I know many teachers in my school are exploring which factors (i.e., racial identity, socioeconomic upbringing, etc.) have shaped their teaching selves and their approaches with their students.

In my classroom, my next step is to help my students continue to dig deeper and analyze how their identities have affected their literary experiences through reflective work like autoethnographies and honest discussions. Instead of focusing on “results,” this school year I’m taking a step back and revisiting my research question: In what ways does a continuous exploration of identity via literature and personal reflection increase engagement and encourage students to become active participants in choosing the books they read both inside and outside their classrooms? I’m realizing the continuous nature of this journey is not something that can be confined to a school year or even two. We will need to delve into who we are, examine the factors that shaped us, and dissect our understanding of the relationship between the two. Only then will we realize the significance of the works we are bringing into our reading lives.

In a survey about the importance of diverse texts from this past November, a response from one of my current seniors struck a chord. It reminded me that thoughtful actions have a powerful impact:

A classroom should be a place where a student can feel safe and recognized for what they do and who they are, whether they like learning or not. Having curriculum emphasize diversity, in this case through texts, is an extremely easy and powerful way to accomplish this. If a student was reading something or being taught something even part of them can identify with, it makes them feel not alone, special even. This would also provide less empathetic students different POV’s. If this is put into action from a young age, I believe it will eliminate a big population of the school that generates hate on students who are “different.” Empathy is necessary, and including diverse texts will achieve this.

—Kyle D., current student

Over the course of my action research project, my students, like Kyle, have taught me how vital it is to not only bring diverse voices into our classrooms but to understand why they’re necessary. Yes, my students and I will benefit from having diverse books in my classroom library, my curriculum, and the summer reading list, but we also need to put in the work to understand the framework that created a mostly homogenous literary canon in the first place. It is only then we can start to dismantle the prejudices and biases that narrow our view of literature and the work we do in our classrooms. As we continue our journey, we need to remember that reading not only reflects and sustains our humanity, but it is also an invitation to center and validate voices that are unfamiliar to us, which, in turn, combats ignorance and hate.

Follow our progress on the Heinemann blog and on Instagram @mrs_jee_ponders.

Julie Kwon Jee is a National Board Certified Teacher dedicated to creating safe classroom environments where students flourish and become lifelong readers and writers. She currently teaches literature, writing composition, and AP English Literature at Arlington High School in LaGrangeville, NY. Julie serves on several teams and committees in her school district, is a founding organizer at EdCamp Hudson Valley, and is a member of the Hudson Valley Writing Project (part of the National Writing Project). Julie is a pioneer in integrating technology and digital tools into literacy learning, and in 2013 was nominated as one of 40 top innovators in education by the Center for Digital Education. Through her robust range of work, Julie seeks to lead by empowering others and bringing equity into the classroom. Follow Julie on Twitter @mrsjjee

Julie Kwon Jee is a National Board Certified Teacher dedicated to creating safe classroom environments where students flourish and become lifelong readers and writers. She currently teaches literature, writing composition, and AP English Literature at Arlington High School in LaGrangeville, NY. Julie serves on several teams and committees in her school district, is a founding organizer at EdCamp Hudson Valley, and is a member of the Hudson Valley Writing Project (part of the National Writing Project). Julie is a pioneer in integrating technology and digital tools into literacy learning, and in 2013 was nominated as one of 40 top innovators in education by the Center for Digital Education. Through her robust range of work, Julie seeks to lead by empowering others and bringing equity into the classroom. Follow Julie on Twitter @mrsjjee

•••