Tom: Here is a great story of teaching and caring, as told to me by Ian Fleischer, a fifth grade teacher in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. As you read it note the lessons we all can learn from it.

Where Does This Kind Of Teaching Fit On The Rubric?

As told to Tom Newkirk

It was the end of the year we were doing a journalism study as the last writing unit. We were doing a newspaper and thought it would be good to go to the Portsmouth Herald and see how newspapers are made. We could bike there. It’s not too far and I had mapped out a route that was safe. So I told my class of fifth graders, “Let’s go on this bike trip.”

They were very excited. Except Amy. Amy was a shy self-conscious girl, not on any athletic teams, quiet, with low self-esteem. I realized that there was some problem here, and I needed to touch base with her. So I took her aside and asked her if she was concerned about the trip. She was evasive: “I don’t think I can make it.” “My bike is broken.” “I don’t have a bike I can use.” “I don’t like to ride a bike.” “I don’t think I can ride that far.” I said, “I can help you with that. I can get you a bike, and we can train together.” She agreed, a big risk for her

I arranged to work with her in an area behind the school where students wouldn’t see her—every day at 11:30 the kids had a special, art or music or gym—and Amy and I would go out back, and nobody would be there for 40 minutes. We worked for two weeks with nobody around. I brought in my son Owen’s bike to school for her. But when I saw her get on the bike, how awkward and tentative she was, I realized that she had probably never been on a bike before. It was very foreign to her. Eleven years old and couldn’t ride a bike.

Eleven years old and couldn't ride a bike

I realized this was not the bike to start her on. I said that was enough for now and I brought in a smaller bike the next day so she would sit on the seat with her feet on the ground and walk, not even worry about pedaling. So first she would move on the pavement, moving her feet, getting the feel of the handlebars, sitting on the seat. It wasn’t more than two days after that she would walk the bike to the grass, and there a small hill and she would pick up her feet and coast down the hill, over and over again. The next step, “Try to coast with your feet on the pedals.” And she would do that. And the next step was “Put your feet on the pedals and brake.” This bike had foot brakes.” So she got used to putting her feet on the pedals and stopping. And I thought that was huge because she knew she could stop the bike.

The next step was “pedal forward.” As the hill straightened out, “Don’t stop. Keep pedaling.” And we made a chart, and I put it in the closet, so other kids couldn’t see it. But we charted how many pedals she did a day. Five pedals to 20 to 50 to 150. We made a bar chart that we would color in together. And that’s how it went for the entire first week. By the end she was pedaling 150 pedals across the field.

She wasn’t frustrated. There was one rainy day, and I said, “Amy, we don’t have to go out today.” But she said, “I want to go out.” I put on my raincoat are we were out in the rain doing this. There definitely was something overriding the embarrassment of not knowing how to ride a bike at 11 years old.

By the end of the first week I definitely didn’t need to coax her at all. So then second week we were doing a little more riding on the pavement, doing what we had done on the grass, learning how to fall—what do you do when you fall. More riding back and forth doing turns. And then we started going up and down the street behind the school, farther and farther (we were still keeping track of the pedals). We kept graphing it—but at some point we stopped because it was just off the charts. And it just became irrelevant because she was pedaling more than you could count. It was more about distance—down the street and around the corner, working on turns.

And that was the whole second week, getting used to pavement and being safe and turning. Getting hand signals. At this point I also moved her up to a larger size of bike. I just went to Papa Wheelies bike shop—I told them what I was doing and they gave me a bike. They gave it to Amy which I thought was great. I made a video of her thanking Papa Wheelies but she was very cool, didn’t make eye contact. Didn’t say much.

So we came to the bike trip. And she was amazing. She biked in the front of the pack, with confidence. About a mile and a half, some potholes and she did amazing and felt really good about it. And for the last two weeks, all of the fifth graders have this swagger—they are done with elementary school and moving on. And Amy had that swagger too—I think because of the bike

A funny part of the story is that the computer teacher, whose room looks out over the back playground, had seen us and how great Amy was doing. And her daughter’s in middle school, and in the new middle school there’s this big banner, a photo of Amy at the head of a pack of kids, smiling, cycling across the new Portsmouth bridge when it opened after repairs—so she continued to bike.

After it was over my principal, who knew this was going on, said this how teaching should go, in math, in reading, everything, meeting the student where they are.

Previously from Tom Newkirk: "'Show Me Your Pig': A New Motto for Assessment"

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

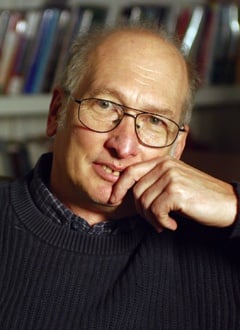

Thomas Newkirk is a Professor English at the University of New Hampshire, and the Chair of the Oyster River School Board. He is the author of Minds Made for Stories: How We Really Read and Write Persuasive and Informational Texts.

Thomas Newkirk is a Professor English at the University of New Hampshire, and the Chair of the Oyster River School Board. He is the author of Minds Made for Stories: How We Really Read and Write Persuasive and Informational Texts.

*Photo by Alexey Lin