I remember being dropped off by my grandma and mom at the airport every May and January for the four years of my undergraduate career—early morning flights with many layovers (because they were the cheapest!) to make my way across the country from southern California to Providence, Rhode Island, as the first in my family to attend college, at Brown University.

I remember being dropped off by my grandma and mom at the airport every May and January for the four years of my undergraduate career—early morning flights with many layovers (because they were the cheapest!) to make my way across the country from southern California to Providence, Rhode Island, as the first in my family to attend college, at Brown University.

At each drop-off, my grandma would give me a $20 bill and say, “No es mucho, pero espero que te alcanze para tu taxi a la Universidad.” “It’s not much, but I hope that is enough to pay for your taxi to campus.” I knew the $20 was a financial sacrifice for my grandma and that it was part of her savings I had depleted, but she did it with love and it was her way of supporting me. I also knew that attending an elite private school was a financial sacrifice for my parents. My family’s yearly income was far less than the yearly $60,000 tuition required to attend Brown, which is why I will forever be thankful for the financial aid package I received that allowed me to attend. However, the anxious knots in my stomach traveled with me as I worried about whether my financial aid and scholarship funds would be applied in time for me to be able to pay for my books and allow me to remain in my classes.

The cost of attending college, across university systems, has increased since when I graduated in 2009; eleven years later, the students in my study continue to have the financial doubts I once had.

For my action research as a Heinemann Fellow, I have explored the following question:

In what ways can a high school community support their first-generation, Latinx college students as they navigate their first and second years at a four-year college setting?

The twenty-four students that are part of this study all depend on financial aid to attend their respective universities in California. As I have collected data including student journals, text messages, and interviews, I’ve concluded and written in Heinemann blogs that there are a number of ways a high school community can support their first-generation, Latinx college students as they navigate their first and second years at college.

I now believe it is imperative that schools work with alumni to provide workshops on financial aid and scholarship opportunities. This information, coming from the trusted and familiar high school community, will ensure that students have access to the funds they need to continue to break down the institutional barrier of the financial costs of college.

Assistance with Financial Aid Applications—A Trusted Friend

Throughout the past two years, I have helped all the students in my study fill out either the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or the California Dream Act Application, both applications for students to apply for financial aid (grants, work-study, and/or loans). This is a process all students attending college will need to complete each year they are enrolled, in order to update their financial information and to qualify for financial aid each year.

Each winter, I sit alongside both the first- and second-year students, their tax information in hand, to apply or renew their applications, hoping they can receive the financial package they need to finance their college education for the upcoming school year. As part of my research data collection, I have asked students why they choose to file these financial aid applications with me (their former high school teacher/administrator) versus filling out the forms with financial aid officers and/or counselors at their college campuses. Their responses are completely reasonable and understandable.

The financial aid application requires students to input sensitive information such as income; there are also some questions that will disclose parents’ citizenship status. Ironically, for some, there are a lot of costs that can emerge in filling out a free financial aid application incorrectly—for example, the cost of disclosing citizenship information that may impact the livelihood of their families. For this reason, all my students mentioned that they preferred to fill out the application with someone they could trust.

Students whose parents are undocumented file taxes using an individual taxpayer identification number (TIN). A student who has a social security number is able to fill out government financial aid applications such as the FAFSA.

Karool Graciano Espino, University of Redlands, 2022

Maria, a freshman at California State University East Bay is an undocumented college student who is part of my study. I knew that Maria had to file the California Dream Act, which is open to undocumented students, and not the FAFSA because I knew she did not qualify for it. At a time when there are strong opinions regarding the Supreme Court’s decision about the constitutionality of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and where there is a president in office who has anti-immigrant sentiments, it was particularly important for Maria to renew her California Dream Act with someone who already knew her.

She reflects, “I chose to complete the Dream Act with you because I feel more comfortable opening up to you and telling you my situation because you already know it. Getting advice and support from you is really helpful and makes me have more hope for my future.” For Maria, the comfort and the prior knowledge I have because of our relationship allows her to avoid stating her status and to remain hopeful about her college journey.

If an undocumented student living in California has attended the equivalent of three full-time years at any combination of California high school, California adult school (including non-credit courses offered by a community college), or California community college, they are eligible to fill out the California Dream Act. Students who have a U visa or temporary protected status (TPS) can also apply. The California Dream Act allows students to pay in-state financial aid at colleges in California and allows students to receive state-administered financial aid such as grants and private scholarships. Students who meet these requirements should fill out the California Dream Act and not the FAFSA.

Jennifer Muñoz, University of California Berkeley, 2023

Twenty-one of the twenty-four student participants in my study are eligible to file the FAFSA, meaning they were born in the United States. However, they have parents who are undocumented. Students are fearful of outing their parents, particularly when filling out a government form, and are selective about those with whom they choose to share this information. They need someone they know will not pass judgement and/or will be confidential, understanding, and empathetic of their situation.

Mariel, a freshman at the University of California Santa Cruz shared, “I feel way more comfortable with you and I trust you more. I know I can go to on-campus resources but I’m very wary when it comes to sharing information about my parents. I fear putting them at risk. I know the school is supposed to protect them from that, right? Regardless, I don’t really like to share information like that with just anybody.”

Edgar does not fill out his FAFSA with his mom; he does fill out the FAFSA with someone he considers to be family and thus is able to ask questions about the application within a safe space. He states, “I feel like I wouldn’t feel comfortable telling other people about my parents undocumented status and what to input when [the application] asks for a social security number but this is possible with you because you are part of my family, in a way, there is a lot of trust and you cannot find that anywhere.”

F is for Financial Aid and Familismo

Edgar echoes the sentiment expressed and emphasized in the research done by Edna C. Alfaro, Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, and Mayra Y. Bámaca. Their research highlights the importance of relational ties between Latinx families, known as familismo. The implications of these findings could be extended to include relational ties that Latinx students form in their social circles outside of the family, including relationships with their high school teachers and administrators and counselors. Relationships with people at school, such as teachers, may be particularly influential (Alfaro, Umaña-Taylor, and Bámaca 2007). I’ve worked to create familismo with my students, and I believe it can make all the difference for students as they navigate the choppy waters of applying to college, obtaining the financial aid they need, and thriving in college.

Ideas for Your School

High schools can host financial aid workshops where trusted advisors meet with students to complete forms. I also field financial aid questions through text messages and FaceTime. Based on my research, I argue that first-generation, low-income Latinx students need more than tax information in hand. They need the safe space that can be provided by trusted people at their high school. They can complete their applications about their familia’s financial situation, within the presence of familia.

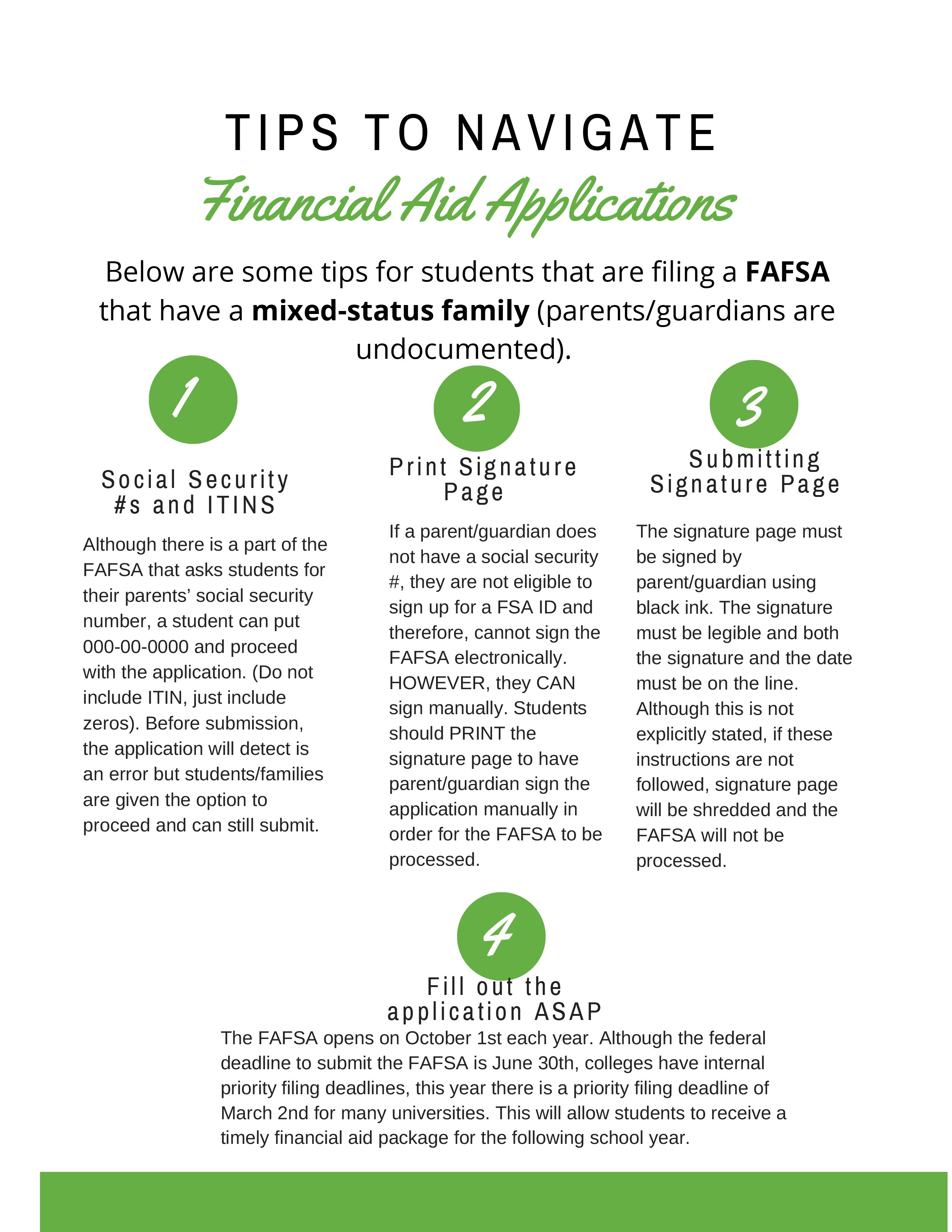

For more tips on how to help students from mixed-status families navigate financial aid applications, please see below.

Irene Castillón (San Jose, CA) is the assistant principal and history teacher at Cristo Rey San Jose Jesuit High School in San Jose, CA, where where she seeks to build structures and programs that affirm students by fostering teaching and learning that is culturally competent and empowering. Irene was also the recipient of the Phyllis Henry Lindstrom Educational Leadership Award and in 2016 and was recognized by the U.S. Department of Education as part of the #LatinosTeach campaign. With her leadership and teaching largely influenced by her own experiences, Irene entered education to advocate for equity, tolerance and justice.

Irene Castillón (San Jose, CA) is the assistant principal and history teacher at Cristo Rey San Jose Jesuit High School in San Jose, CA, where where she seeks to build structures and programs that affirm students by fostering teaching and learning that is culturally competent and empowering. Irene was also the recipient of the Phyllis Henry Lindstrom Educational Leadership Award and in 2016 and was recognized by the U.S. Department of Education as part of the #LatinosTeach campaign. With her leadership and teaching largely influenced by her own experiences, Irene entered education to advocate for equity, tolerance and justice.

*Work Cited

Alfaro, Edna C., Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, and Mayra Y. Bámaca. 2006. “The Influence of Academic Support on Latino Adolescents’ Academic Motivation.” Family Relations 55: 279–291.