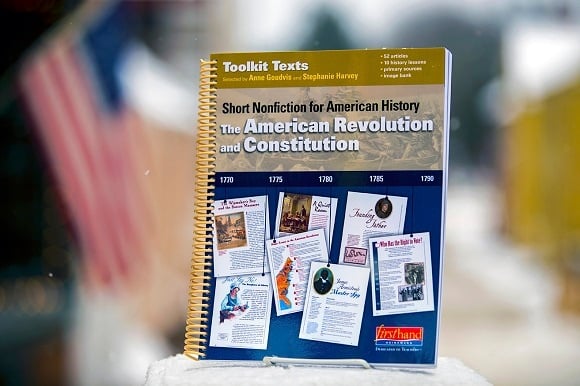

The second resource in the Toolkit Texts series, Short Nonfiction for American History, is out now. In several blogs over the next few weeks, coauthors Anne Goudvis and Stephanie Harvey share their perspectives and insights into historical literacy.

by Anne Goudvis and Stephanie Harvey

The active literacy history classroom is awash with rich, engaging resources of all kinds: images, short texts, maps, artifacts, time lines, poems, historical fiction, on-line resources, and biographies. When kids encounter unexpected events, quirky individuals, and surprising information, they become immersed in the dramas and experiences of the times. There is not a worksheet or end-of-chapter question in sight as kids read, write, draw, talk, view, question, and discuss. And research supports this approach: Allington and Johnston (2002) found that students demonstrated higher achievement when classroom instruction focused on a multi-source, multi-genre, multi-perspective curriculum rather than a one-size-fits-all coverage approach.

Our upcoming blogs will introduce several comprehension practices that we believe are essential to building kids’ historical literacy. For the next two weeks, we’ll focus on reading and annotating all kinds of texts using a variety of strategies to build content knowledge. To turn information into knowledge, kids actively annotate their new learning, their questions, and their responses on a variety of sources.

Annotating texts of all kinds is a powerful thinking tool. Kids engage in thinking-intensive learning: they paraphrase, summarize, analyze, and react to new information. This gives them the best shot at understanding and remembering important information and big ideas in history.

Practice #1—Annotate images: Expand learning and understanding from visuals

We often begin with annotating images to get kids engaged in an iconic historical event, such as this famous painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware at the Battle of Trenton (by Emanuel Leutze, 1851). Students view and observe closely, leave tracks of their thinking, and discuss their questions, inferences and interpretations. Often we pose a question or two to focus their thinking and guide their observations: Who created this? Why and when was it created? What do you think is the author/artist’s purpose or perspective?

A group of fifth graders who had read an account of the Battle of Trenton and a primary source diary entry about Washington’s army crossing the Delaware River (see the American Revolution and Constitution: Short Nonfiction of American History collection of primary sources) were asked to carefully observe this painting as part of studying these events. Here are some of their comments:

Wait a minute, it says this was painted in 1851—that’s way after the American Revolution! How did the painter know what happened? He must have used his imagination to paint this.

But we read it was cold and rainy that night—there’s ice in the river, so that is accurate. When we read about it, it happened at night. But it is not night in the picture.

I think that boat would sink if it had all those people in it! It shows lots of action and that it was dangerous…

The men are all pretty brave, especially Washington standing up when it was so rough. I wonder if they really had a flag like that.

♦ ♦

Gallery Walks

When we begin a study of a historical time period or topic, such as the American Revolution, we often start with a gallery walk, posting or projecting images of women, men, and children who are connected to these events. We include colonists, indentured servants, enslaved people and Native Americans, in addition to the founding fathers (with over 60 historical images in the image bank for American Revolution and Constitution: Short Nonfiction of American History, we have plenty to choose from).

We pose the question “Whose revolution was it?” This prompts kids to think about the people described in the pages of their history books: who we remember and why we remember them. The images and short captions spark questions about lesser-known and unrecognized individuals who played important roles in historic events.

Responding to and discussing images piques kids’ interest—and we are ready with additional articles and resources that kids can read to find out more information. We always keep in mind ways to tie practices such as this back to our goal of teaching kids to think like historians. So we wrap up by asking them to consider how images and visuals help us better understand a historical event or topic.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Anne Goudvis and Stephanie Harvey have enjoyed a fifteen-year collaboration in education as authors and staff developers. They are coauthors of the Heinemann title Comprehension Going Forward and of Strategies That Work. They have also created a family of bestselling classroom materials under Heinemann’s firsthand imprint: The Comprehension Toolkit, The Primary Comprehension Toolkit, Toolkit Texts, Comprehension Intervention, Scaffolding for ELLs, and Connecting Comprehension and Technology. Their newest resource, Short Nonfiction for American History, is discussed in this blog post