The following is an adapted excerpt from When Kids Can’t Read: What Teachers Can Do, 2/e, by Kylene Beers.

Improving Fluency

If I see that a student is scoring far below the average reading rates, then I know I must help the student with fluency. Sometimes fluency problems are not a result of poor word recognition or a lack of automaticity. Sometimes children have tracking problems with their eyes. If students constantly lose their place while reading, tracking might be a problem. If you suspect this, make sure you let parents know immediately so they can get their child to the ophthalmologist.

Other students are simply easily distracted. They aren’t paying attention to what they are reading—whether silently or orally—so they lose focus. If you hear a lot of “ums” in between words while students are reading aloud, that may be the problem.

And still other students slow down as they read an unfamiliar text. If that’s the case, consider doing more prereading activities to help students prior to reading the activity. When the issue is, however, that students simply have not developed the fluency they need, try the following suggestions.

1. High-Frequency Words

Sight words are generally considered to be those words that students need to learn by sight because they don’t follow regular decoding rules (e.g., have, does, give, been). The reality is, though, all words that we decode automatically have become sight words. Often we use the term “sight word” when we mean those words that are spelled irregularly. High-frequency words are those words that appear so often in texts that automatic recognition is helpful. Students need to be able to recognize both irregularly spelled words and high-frequency words instantly.

Blevins (2001), building on the work by Johns (1980), Fry, Kress, and Fountoukidis (1993), Adams (1990), and Carroll, Davies, and Richman (1971), offers these numbers:

- Of the approximately six hundred thousand–plus words in English, a relatively small number appear frequently in print.

- Only thirteen words (a, and, for, he, is, in, it, of, that, the, to, was, you) account for over 25 percent of the words in print, and one hundred words account for approximately 50 percent.

- The Dolch Basic Sight Vocabulary contains 220 words (no nouns). Although this list was generated over forty years ago, these words account for over 50 percent of the words found in textbooks today.

Spend some time making sure your disfluent readers know these words. It takes very little time to call a student to a conferencing area of the room and simply run through the words. If this looks like out-of-context reading, that’s because it most certainly is. I want to see how quickly students can recognize the most frequently seen words in the least contextual environment. I’ve found that if a student can quickly recognize because written alone on an index card, then he generally can recognize it in a sentence. If a student can’t recognize the word in isolation, then he may or may not be able to recognize it in context. I want students to definitely be able to recognize it in context—not sometimes, not when the contextual clue is obvious enough, but all the time.

You can reinforce high-frequency words with word walls. Word walls are a powerful way to get words in front of students for constant reinforcement. Find a space on your wall where you can put up words, arranged alphabetically. Write the words large enough that students can see them easily from a distance. Avoid building a word wall prior to the first day of class so that it is up when students arrive. That word wall would belong to you. Instead, have the portion of the wall you’ll be using marked and divided into a grid labeled with letters of the alphabet so that students know where to put specific words, and then build the word wall with the students. Now it’s theirs. For a high-frequency word wall, I often ask students to look at a few pages of text and find some words that appear over and over. They find words like of, a, the, at, that, but, have, very, would, about, had, and if with little trouble. I (or a student) write one word on a card (again, use big print and a marker), and then we put the word under the correct letter.

Finally, help students learn high-frequency words through lots of reading. This is difficult because students who need help reading high-frequency words are our slowest readers, so giving them time to read means giving them books they can read and then lots of time to read those books. If we don’t give these slowest readers time to read, they will never be anything other than a slow, disfluent reader.

2. Give Students Varied Opportunities for Hearing Texts

Students need to hear fluent reading in order to become fluent readers. Make sure as you are reading aloud to students, you are modeling good expression, good phrasing, and good pacing. Keep in mind that you can model fluent reading by reading aloud just a few pages from the chapter students are reading or the short story they are about to read. Smith (1979) reminds us that when students listen to a teacher read aloud a few pages of a text they are about to read on their own, and follow along as the teacher reads, these students then complete the story with better fluency and accuracy.

- Echo reading in small or large groups improves fluency. In echo reading, the teacher reads aloud a short passage, modeling strong phrasing, and then students repeat the same passage, mimicking his reading. As with comprehension instruction, begin an echo reading lesson with specific information:

“As I read the following passage, note how I raise my voice at the end of sentences that are questions.” Again, if you think your students don’t need this level of practice, then move to other strategies. - Choral reading is similar to echo reading except the teacher isn’t reading the passage first with students echoing afterward. Choose a few lines that offer a specific reason to be read aloud. Perhaps there’s a section of dialogue between two characters, one who is whispering while the other is shouting. One part of the class can read the shouting character’s words while the other responds with the whispered text. The point of choral reading is to work on a specific aspect of fluent reading.

After any type of oral reading—whether it be a read-aloud from you, echo reading, or choral reading—ask students what they noticed about how the dialogue was read, how statements and questions were read differently, how excitement was added, how a character’s emotions were captured through stress and intonation. Ask what they noticed about the phrasing and the pacing. Remember, in the beginning, their answers might vary between the ever-ready “I don’t know” and the frustrating shoulder shrug. Then, you have to model answers. It also might mean you aren’t exaggerating the reading enough. Students must hear the features you want them to understand.

3. Teach Phrasing and Intonation Directly

It’s one thing to model fluent reading and another to directly teach students how to use correct phrasing and intonation. You can do it by sharing a series of sentences and asking students to read them (through choral reading, echo reading, or reading by individual volunteers) following the directions you give. The goal is to show students that how you read a text can make a difference in what you understand about the text.

Don’t assume that nonfluent readers naturally understand this. The reality is, they probably don’t give phrasing and intonation much thought. You’ve got to show them directly how stress on certain words can make a difference in meaning. Try it with this example:

Read the following sentences aloud. In each sentence, stress the word that is underlined:

You read the book.

You read the book.

You read the book.

You read the book.

Why did your voice change as you read each sentence?

4. Have Students Reread Selected Texts

One of the best ways to improve fluency is through the repeated rereading of texts (Samuels 1979). Let the student read an instructional-level text aloud. You time him for a prearranged number of minutes (one to five is fine). Afterward, discuss any miscues the student made and count the number of words per minute the student read accurately.

Record this on a chart. Then let the student reread this passage two more times. As students reread, they are focusing on correcting the miscues they made previously and improving their phrasing and rate. Recording the data gives students a record of their reading-rate improvement over time.

5. Prompt—Don’t Correct

Often when non-fluent readers read aloud, their reading is interrupted not only by their own pauses but by other students (or teachers), who tell them the word that is causing the pause. Whether we do this out of kindness, out of frustration, or because we don’t know other strategies, telling the dependent reader the word encourages more dependence. On the other hand, letting the student stare at the word indefinitely doesn’t help either. The alternative to correction is prompting.

Prompting means giving the student the prompt he needs to decode the word successfully on his own. The simplest prompt is “Read that again.” Sometimes starting the phrase or sentence over again gives the student an opportunity to recognize a word. Other times, the prompt needs to be more explicit:

- Can you divide the word into syllables and sound it out that way?

- Do you see a part of the word you recognize?

- Can you think about the letters and the sounds they make?

- Can you try sounding it out slowly to see if that helps?

If none of those prompts helps, then you need to tell the student the word. As you do, can you remind them of certain sounds particular letter combinations make? For instance, sh makes the sound heard at the beginning of shoe; kn makes the sound heard at the beginning of not; ph makes the sound heard at the beginning of fun; -ing makes the sound heard at the end of sing. Then, have the student start that sentence again, reading the word without your prompt. Providing the word and then letting the student read on doesn’t benefit the student.

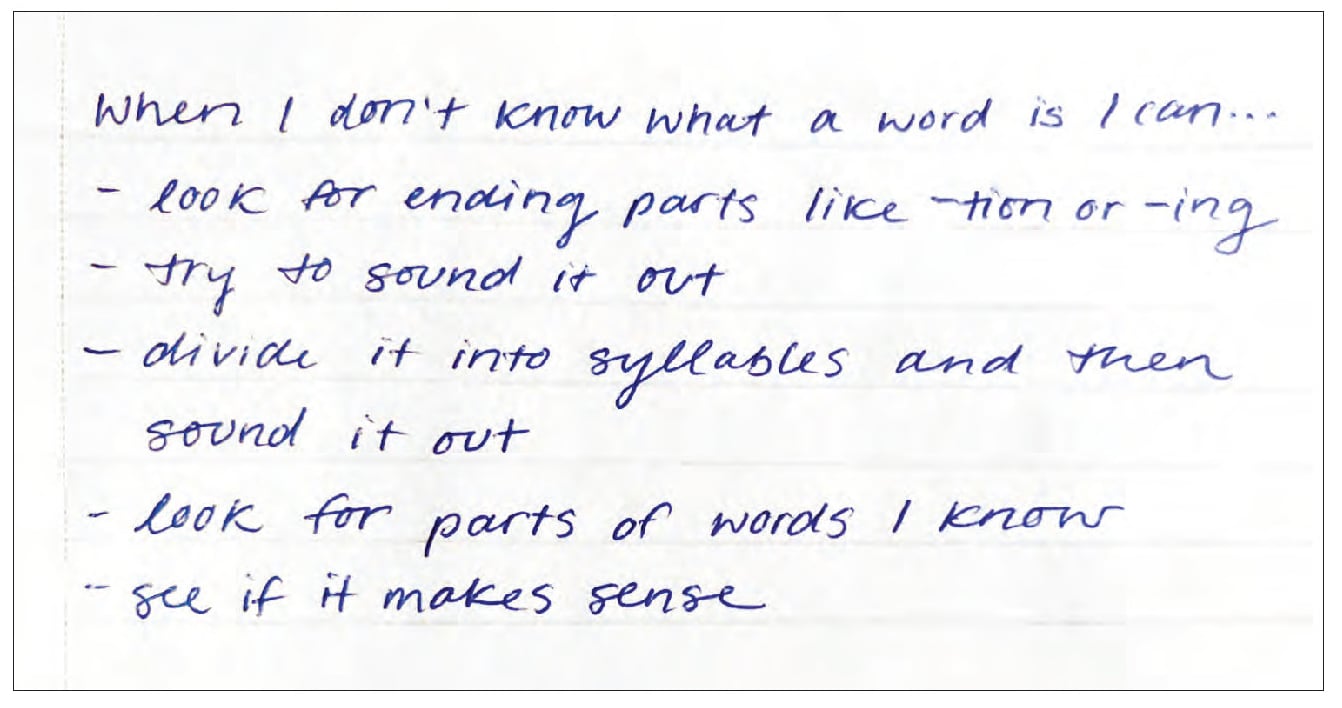

The goal with prompting is to move away from correcting. I’ve seen students read aloud, pausing between words to wait for the teacher’s nod of approval. I’ve watched other students read until they come to a word they don’t know, pause, wait for the teacher to insert the correct word, and then read on, never saying the word that gave them trouble aloud. Correcting rarely fosters independence. Prompting so that the student is in control of figuring out the word contributes to independence. You can strengthen the power of prompting by asking students, when they’ve finished reading, to identify what they did when they came to a word they didn’t know. Let them keep a list of strategies they use. The figure below shows you one eighth grader’s list of strategies for tackling words she doesn’t know.

Questions to Ask Yourself

Disfluent readers are most often disfluent because of a lack of practice with reading. We cannot confuse teaching about reading with the act of reading. Ultimately, struggling readers must have a lot of time to read at their instructional or independent level. Furthermore, we must examine our own instructional practices with these students. Ask yourself these questions.

Questioning My Fluency Practices

- How often do I give students instructional- or independent-level texts to read?

- How much time in my class do I give students to read?

- How often do I read aloud to students? Do I read aloud different genres? Poetry sounds different from a science text; math problems sound different from a novel.

- When struggling readers read aloud, do I correct their mistakes or prompt them to correct their own mistakes?

- What prompts do I offer students?

- How often do I use echo reading or choral reading?

- How often do I discuss with students why I read a certain passage a certain way?

- Do I remind students to transfer what they’ve been doing with oral reading to their silent reading?

- Do I ask students to pause while they are reading silently to reflect on how the reading sounds in their mind?

- Do I give students specific instructions before they begin to read silently about how the reading should sound in their mind?

As you reflect on those questions, you’ll probably find ways to improve some of your instructional practices. What’s rewarding about reading instruction is that as we become better teachers of reading, students become better readers.

Kylene Beers, Ed.D., is a former middle school teacher who has turned her commitment to adolescent literacy and struggling readers into the major focus of her research, writing, speaking, and teaching. She is author of the best-selling When Kids Can’t Read/What Teachers Can Do, co-editor (with Bob Probst and Linda Rief) of Adolescent Literacy: Turning Promise into Practice, and co-author (with Bob Probst) of Notice and Note: Strategies for Close Reading and Reading Nonfiction, Notice & Note Stances, Signposts, and Strategies all published by Heinemann. She taught in the College of Education at the University of Houston, served as Senior Reading Researcher at the Comer School Development Program at Yale University, and most recently acted as the Senior Reading Advisor to Secondary Schools for the Reading and Writing Project at Teachers College.

Kylene has published numerous articles in state and national journals, served as editor of the national literacy journal, Voices from the Middle, and was the 2008-2009 President of the National Council of Teachers of English. She is an invited speaker at state, national, and international conferences and works with teachers in elementary, middle, and high schools across the US. Kylene has served as a consultant to the National Governor’s Association and was the 2011 recipient of the Conference on English Leadership outstanding leader award.

Kylene is now a consultant to schools, nationally and internationally, focusing on literacy improvement with her colleague and co-author, Bob Probst.