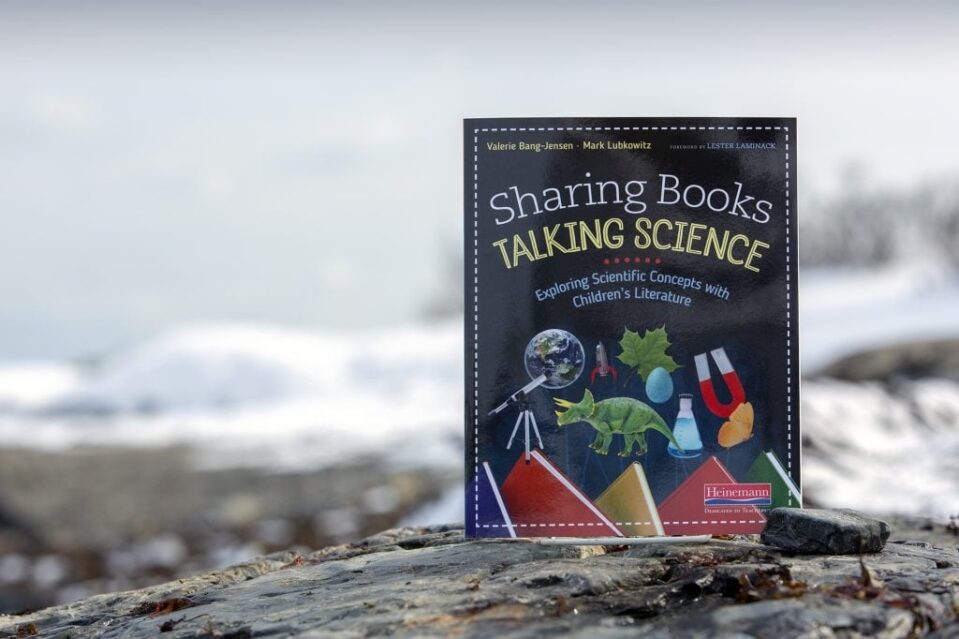

On Today’s podcast — exploring science in children’s literature. Science is everywhere, in everything we do, see, and read. All books offer possibilities for talk about science in the illustrations and the texts… once you know how to look for them. Children’s literature is a natural avenue to explore the seven crosscutting concepts described in the Next Generation Science Standards. In their new book: Sharing Books, Talking Science, authors Valerie Bang-Jensen and Mark Lubkowitz help teachers develop the mindset necessary to think like a scientist, and then help students think, talk, and read like scientists. We started our conversation on how the idea for this book came to be and what they call “the surprisingly powerful friendship of children's literature and science.”

On Today’s podcast — exploring science in children’s literature. Science is everywhere, in everything we do, see, and read. All books offer possibilities for talk about science in the illustrations and the texts… once you know how to look for them. Children’s literature is a natural avenue to explore the seven crosscutting concepts described in the Next Generation Science Standards. In their new book: Sharing Books, Talking Science, authors Valerie Bang-Jensen and Mark Lubkowitz help teachers develop the mindset necessary to think like a scientist, and then help students think, talk, and read like scientists. We started our conversation on how the idea for this book came to be and what they call “the surprisingly powerful friendship of children's literature and science.”

See below for a full transcript of our conversation:

Mark: This started in, I think it was about our fourth year at Saint Michael's College. I'm in the biology department, and Valerie is in the education department. She was at the time teaching a graduate class-

Valerie: In nonfiction, for elementary teachers.

Mark: Valerie asked me if I would be a guest speaker in her class. And being a professional profession I said, "What do I need to prepare to come to your class?" And she, "Don't do anything. Just be the scientist that you are."

Valerie: What I really said was, "Bring your science brain." The reason I did that, I had read about this idea somewhere else, and it made a lot of sense to me. My elementary teacher students, were really used to sharing books with children and talking about fiction elements. This story, the plot, the illustrations, and the connection with the text, they were fabulous about that.

But I wanted them to see that every reader brings a certain lens to a reading experience. The best way to do that was to invite Mark to bring in his science brain.

Mark: You read Winter Barn to the class.

Valerie: I did. I asked them, "What did you think? Talk about the book?" They noticed the pen and ink drawings, very spare, very quiet, very winter mood. The text matched that, very poetic. I turned to Mark and I said, "Mark, what did you see?"

Mark: And I said, "It's clearly a horror story." Very simply because there are predators and there are prey in the barn living together. Not everyone is going to be happy or even alive at the end of the winter. Some of the characters will be in somebody's belly, and digested, and used as an energy source.

Brett: How did the students react when you shared those observations?

Valerie: Part of it was they started to recognize that they could have gone there, maybe not as far as Mark did, in terms of seeing a system, and energy, and stability, and all of that technical terms. But they started to see that, "Oh yes, all those things were present." They just needed a way in to seeing those elements.

Mark: It also empathized that they way that you're trained professionally, really does influence how you see the world. It would be hard for me not to see that story in that context. That's my first glance, and I have to constantly change to a different lens when I read a story like that.

Valerie: Can I tell you, I will never be the same after writing this book with Mark. Yesterday I ran into a colleague in the hall, and she said her husband had just been in a motorcycle accident. His shoulder blade was broken and he couldn't go to work. Her mother-in-law was there, and everything was upside down. I sympathized and as I was walking along after that I said to myself, "It's a system in change." I never would have thought of it that way before, but that just went right into my head.

Mark: And I'll tell you, it permeates my household. For example, when we had the unfortunate pleasure of all four of us having the stomach bug at the same time a couple months ago. So we had literally every toilet and every sink being used at the same time. I looked at my children and I said, "Do you want to know the mechanism of why you're currently throwing up?" Then I went to explain what the virus was doing, and which transporters were being activated in their gut, and how that was changing osmolarity. I asked them if that made them feel any better. And they said, "No." But mechanism, the point there being is that as a scientist, I never stop thinking about mechanism.

Brett: Even on your worst day?!

Mark: Even on my worst day.

Brett: Well Valerie, I want to go back to something that you said. You said, "I never thought about it this way", which seems to be how people immediately react when reading this book. It made me think about the theme that you have throughout the book of developing our lens. Why is that so important for us?

Mark: Can I jump in?

Valerie: Yeah. I'm still thinking but you jump.

Mark: Valerie and I wear these little buttons to graduation every year. We made them, we printed them for our first year seminar class many years ago. What they say is, "Embrace complexity." At the centerpiece of our pedagogy for both of us, is that the world is a really complicated place. And that solving real problems, difficult problems, requires an approach from many, many perspectives.

Even if you have just your perspective, you need to be able to communicate it and understand other people's perspectives. So takes something really big like global climate change, you definitely science at the table, but you need economists, you need educators, you need political scientists, you need the business community. There's a lot of voices that have to be heard at that table.

Education traditionally has been very siloed, in that you're in your department, and you're learning what's in your department, and in your major. In many schools, including ours, is doing this. But Valerie and I want to be very intentional about breaking outside of our departmental boundaries, and looking at the world through multiple lenses.

Valerie: I think it commonly happens in elementary schools. For example, many are developing school gardens, or recycling and composting. Smart elementary teachers realize that those are inter-disciplinary processes or projects. You can see the math in it, you can see the science, you can get involved with literacy, developing signage or instructions.

I think that the elementary lens already does this. You look at how can we learn about this topic or this theme? What are all the different ways we can examine it? But I think what I was lacking before was the terminology and the conceptual understanding of these cross-cutting concepts. Now that I have that, my ability to integrate in all these topics in elementary school, is much richer and more accurate. I feel really confident about it.

Brett: And speaking of confidence… you write about how elementary teachers need to be generalists and essentially need to know everything. How can this book help teachers with that confidence in bringing more science into their instruction?

Valerie: Well as I mentioned, I think that knowing the terms and knowing these concepts, they really are cross-cutting in the sense that you see them in everything. I start to see them when I'm walking down the hall talking to a colleague. I start to see them in illustrations. I can't unsee them anymore. Now that they're part of my lens, it makes me understand things. It makes me look for the mechanism, like Mark was saying. It makes me see that something is in change, but it will return to stability. I think that now that I have that lens, if I'm in a classroom, I see so many opportunities to launch that into the discussion of anything.

Mark: We were also very intentional about the types of examples that we chose. We made them classroom based, so when we were deconstruction any given concept, the examples that we used are found in probably every classroom in America. Furthermore, one of the things that we noticed while writing it, and I don't think we started in this place, but we ended in this place, is that language already hints at all the cross-cutting concepts.

For example, every time one of us says, "Because", really what [inaudible 00:07:30] saying is we're giving foreshadow to, "I'm about to tell you the cause."

Brett: There was a section I really liked a lot where you write about, you say books about scale. You highlight that not only words carry weight, but so do the illustrations. Can you explain a little bit more about that?

Valerie: Sure. There's some books where it's a tool that authors use, like Steve Jenkins. Just his book Actual Size, we know right then and there, how big something is because he gives you a picture of the gorilla's hand that's mathematically accurate. But then there are other books where you can talk about scale, you can see that something's far away because the people are really small. Or you can see that this tree, this tree that someone planted, has grown over the years, because the person next to the tree is tiny compared to the tree.

Mark: We looked at a book that had an illustration of tumbleweeds. Let's say that you're from New England, and you've never seen a tumbleweed. The only thing that gave you an inkling of what the actual size was, was an animal, small mammal that was next to it. So instantly any reader would be able to know what's the size of a tumbleweed. "Well, it's about three times larger than that small dog."

Brett: That's great. You also talk about the challenge of time for this idea, and the importance of mindset for making the strange familiar. Can you talk a little bit more about that, and the importance of read alouds?

Valerie: Sure. I think that one thing that Donald Gray said the first time I ever heard him speak, was that we have a cha-cha-cha curriculum. I think what I took that to mean was that we have so many things to cover, that it's hard to find the time to uncover things. That people keep adding to the curriculum, important thing, but they never say what to stop doing, and they don't give us more time.

So classroom teachers, and I work with student teachers a lot, and they're surprised to see how time affects everything that they do. In a climate of testing, where most of the testing is about literacy and math, science often gets relegated to once a week, or if we have time, or if we finish. So this doesn't replace science inquiry, but it's something that you can talk about in any discussion whenever you read aloud. By discussing in a read aloud, the illustrations, it's a point where students can start to use that lens. So they're looking at a familiar illustration, but they're stepping back and trying to apply something new.

Mark: I think the key word is habits of mind. It's a habit of mind of scientists, and developing a habit is just that. You need to do it frequently or even daily, ideally.

Brett: As we wrap up, what are your thoughts, what are your hopes for the book in terms of influencing classroom practice?

Mark: One of the things that I always say to my students at Saint Michael's, is if it happens, there is a cause and there's a mechanism. My biggest hope and dream is that there will be a generation of people who start to think about mechanism, so that if you see something occurring, you don't accept it for just, "Oh that happened." You're like, "Huh, I wonder how that happened?"

Valerie: The way that I think about it, or what I'd like to see happen, is the aha that Mark and I had when we started to notice how many linguistic cues there are to these cross-cutting concepts. It's not really layering science onto everything else, it's digging it out. I think one thing that it did for me was, it enriched my reading experience, because I started to see, "Wow, there's cause and effect everywhere. And what is the mechanism? It was when that character did this."

Same thing with stability and change. Plot structures are all about stability and change of a system. And so the science is enriching the literature and visa versa.

Mark: And we're all natural scientists, that's the things about it. We're physical beings, we live in a physical world, we interact with gravity everyday, and we even know how to do it, even before you know the word gravity. So part of it is giving kids that vocabulary and that lens to start to see what they already and to name it, and become familiar with it.

For more information (including a sample chapter and videos): Sharing Books, Talking Science

Valerie Bang-Jensen is Professor of Education at Saint Michael’s College. She earned her A.B. at Smith College and MA, M.Ed., and Ed.D. degrees from Teachers College, Columbia University. Valerie has taught in K-6 classrooms and library programs in public and independent schools in the U.S. and Paris, and was the district elementary writing coordinator in Ithaca, New York. She serves as a consultant for museums, libraries, schools and gardens for children.

Valerie Bang-Jensen is Professor of Education at Saint Michael’s College. She earned her A.B. at Smith College and MA, M.Ed., and Ed.D. degrees from Teachers College, Columbia University. Valerie has taught in K-6 classrooms and library programs in public and independent schools in the U.S. and Paris, and was the district elementary writing coordinator in Ithaca, New York. She serves as a consultant for museums, libraries, schools and gardens for children.

Mark Lubkowitz is Professor of Biology at Saint Michael’s College, where he received the Joanne Rathgeb Teaching Award. He earned a B.S. in Biology at Washington and Lee University and a Ph.D. in Molecular Biology from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He was a post-doctoral fellow in plant developmental genetics at the University of California, Berkeley. As a scientist, Mark studies the molecular mechanisms of transporters and the various roles they play in plants.

Mark Lubkowitz is Professor of Biology at Saint Michael’s College, where he received the Joanne Rathgeb Teaching Award. He earned a B.S. in Biology at Washington and Lee University and a Ph.D. in Molecular Biology from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He was a post-doctoral fellow in plant developmental genetics at the University of California, Berkeley. As a scientist, Mark studies the molecular mechanisms of transporters and the various roles they play in plants.